In 1977, when Manuel Castells’ classic book, The Urban Question, was first put into English, I’d been a year out of high school, in Liverpool. It was five years after its original French publication, four years since an OPEC oil embargo had sent advanced economies into giddy noise dives, and a year on from the Sex Pistols’ debut hit, Anarchy in the UK. These were heady times, the 1970s, full of crises and chaos, a post-1968 era of psychological alienation and economic annihilation, of Punk Rock and Disco, of Blue Mondays and Saturday Night Fever. The decade was also a great testing ground for a book bearing the subtitle, A Marxist Approach. Indeed, the same year as The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach became available to Anglophone audiences, the Sex Pistols were screaming, “THERE’S NO FUTURE, NO FUTURE FOR YOU AND ME!”

I didn’t know The Urban Question back then, nor much about Marxism; I was eighteen, hardly read anything, and remember most of all the candlelit doom of Callaghan’s “Winter of Discontent.” Power cuts, strikes and piled up rubbish seemed the social order of the day. And the Sex Pistols’ mantra of NO FUTURE seemed bang on for my own personal manifesto of the day. I became, largely without knowing it, something of a fuck-you anarchist, not really knowing what to do, apart from destroy—usually myself: “what’s the point?” Johnny Rotten had asked. I didn’t see any point. The decade was dramatized by sense of lost innocence. I watched my adolescence dissipate into damp Liverpool air, into a monotone gray upon gray.

It was only in the early 1980s that I first learned to read and write to survive. By then, Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister and I’d discovered something never encouraged at school: I loved to write, loved to write about things I’d read, about things I’d done, people I’d met. Before long, I’d gained access to the local Polytechnic as a “mature student,” as a second-chance scholar, as a scholar-with-attitude. That as the Thatcherite project was in full flight dismantling welfare statism; multiple levels of local and national government felt Thatcher’s “free market” heat, got abolished, abused, and recalibrated to suit the whims of an ascendant private sector.

This posed some pretty tough intellectual and political questions for my friends and I at Liverpool Polytechnic, as we passed our time wondering how to intellectually fill the post-punk void. We hated the bourgeois state with serious venom. We wanted to smash it, rid ourselves of its oppressive sway. So when Thatcher started to do just that, we were left wondering where to turn? Did we want that nanny state back? Life had been boring and programmed with it, but maybe things were going to be much worse without it?

In retrospect, 1984 seems a watershed, the significant year of contamination: Ronald Reagan had begun his second term and the Iron Lady had survived the Brighton Bombing; the IRA’s attempt to finish Thatcher off had the perverse effect of only setting her more solidly on her way, propelling her full-kilter into dismantling the post-war social contract between capital and labor, taking on (and taking out) organized labor and organized opposition in the process; Arthur Scargill and the miners, as well as Militant in Liverpool, took it full on the chin.

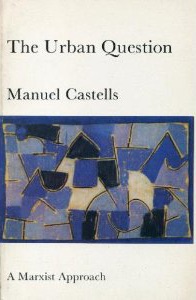

It was then that I discovered Castells’ The Urban Question. The major thing that immediately struck me, I remember, was its cover: Paul Klee’s Blue Night. Only recently—very recently in fact, this past January at a London Tate Modern Klee retrospect—did I eventually see for myself Klee’s enigmatic canvas, from 1937, one of his last, an unusually expansive (50X76cm) work in an oeuvre characterized by intricacy and smallness. For a long while Blue Night was one of my favorite paintings. I’d always wondered whose choice it had been to have it adorn a book about Marxism and the city? Castells’ own? I still don’t know. The other thing that intrigued me about The Urban Question was its heavy Althusserian Marxism. I’d borrowed Louis Althusser’s For Marx from the Poly library, trying to figure out what was going on. Little made sense initially. Only a lot later did I recognize how Castells mobilized in original and idiosyncratic ways twin pillars of Althusserian formalism: ideology and reproduction.

It was then that I discovered Castells’ The Urban Question. The major thing that immediately struck me, I remember, was its cover: Paul Klee’s Blue Night. Only recently—very recently in fact, this past January at a London Tate Modern Klee retrospect—did I eventually see for myself Klee’s enigmatic canvas, from 1937, one of his last, an unusually expansive (50X76cm) work in an oeuvre characterized by intricacy and smallness. For a long while Blue Night was one of my favorite paintings. I’d always wondered whose choice it had been to have it adorn a book about Marxism and the city? Castells’ own? I still don’t know. The other thing that intrigued me about The Urban Question was its heavy Althusserian Marxism. I’d borrowed Louis Althusser’s For Marx from the Poly library, trying to figure out what was going on. Little made sense initially. Only a lot later did I recognize how Castells mobilized in original and idiosyncratic ways twin pillars of Althusserian formalism: ideology and reproduction.

Unlike Althusser, this was Althusserian formalism applied to the real world, to the conflictual urban condition of the 1970s, to the fraught decade when capitalism attempted to shrug off the specter of post-war breakdown, the decade when I attempted to shrug off my own crisis, a coming of age in an age not worth coming of age in. Moreover, although this urban system was declining, was in evident trouble everywhere, collapsing entirely it wasn’t. Castells wanted to know why. “Any child knows,” Althusser had said in his famous essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” “that a social formation which did not reproduce the conditions of production at the same time as it produced would not last a year.” The citation, a paraphrase of Marx, in a letter to Dr. Kugelmann (July 11, 1868), summed up the whole point of Volume Two of Capital: without reproduction there could be no production; without the realization of surplus-value, no fresh surplus value could ever get produced; production is predicated on extended and expanded reproduction. And yet, given inevitable ruptures in the “normal” functioning of capitalist production, how come capitalism survived then, still survives?

Althusser actually passed over all the stuff about reproduction of capitalist relations of production from Volume Two of Capital, passed over those political-economic “reproduction schemas” that Marx conceptualizes, and beds his vision down in the ideological reproduction of labor-power, in his own particular notion of ideology: “an imaginary representation of an individual’s real conditions of existence.” Consequently, in The Urban Question, Castells attacked urban studies precisely because of its ideological content. Erstwhile research on “the city,” he’d said, had formulated “imaginary representations,” framing the city in terms of “urban culture,” in narrow sociological and anthropological terms. Such approaches focus on “dimensions of the city,” on “densities,” on “size,” on the idea that the city exhibits a particular specificity, its own of organization and transformation; a logic which, Castells said, pays scant attention to broader dynamics of capitalist political-economic and social relations, particularly to their reproduction.

So in The Urban Question Castells said the urban isn’t really a unit of production at all; production operates at a bigger scale, at least on a regional scale and increasingly international stage. Production isn’t the right analytical entry point into the urban question. Rather, it is, à la Althusser, reproduction that counts most, the reproduction of the urban system and its links to the overall survival of capitalism. The urban, Castells insisted, typically awkwardly, is “a specific articulation of the instances of the social structure within a spatial unit of the reproduction of labor-power.”

From the mid-1970s onwards, around the time the Sex Pistols announced “NO FUTURE,” Castells began to define and refine his notion of the urban as the spatial unit of social reproduction by coining the concept “collective consumption.” Collective consumption is implicit in the reproduction of “unproductive” collective goods and services outside of the wage-relation, outside of variable capital, items like public housing and infrastructure, schools and hospitals and collectively consumed services. “The essential problems regarded as urban are,” Castells said, “in fact bound up with the processes of ‘collective consumption’… That is to say, means of consumption objectively socialized, which, for specific historical reasons, are essentially dependent for their production, distribution and administration on the intervention of the state.”

And yet, what arose over the decade was an awkward predicament for progressive people, and for Marxist theoreticians: items of collective consumption so vital for reproduction of the relations of production, so vital for freeing up “bottlenecks” in the system, so vital for providing necessary (yet unprofitable) goods and services, so indispensable for propping up demand in the economy—were now being cast aside. How could this be? What once appeared essential ingredients for capitalism’s continued reproduction—for its long term survival—now turned out to be only contingent after all; the state began desisting from coughing up money for them; and soon, as the 1980s kicked in, would actively and ideologically wage war against them.

The Left has never really come to terms with the shock waves this earthquake engendered; the seismic tremor that registered big digits on the neoliberal Richter Scale. The 1980s bid adieu to social democratic reformism, to an age when the public sector was the solution and the private sector the problem. The former now needed negating, pundits and ideologues maintained, required replacement by its antithesis; now the private sector was the solution and a shot and bloated public sector the problem. Managerial urbanization—when state bureaucrats dished out items of collective consumption through some principle of redistributive justice or vague notion of equality—had given way to an urbanization in which the market was the panacea. Writ large was the beginning of the privatization of everything.

Thatcher’s assault on welfare provision and blatant class warfare created a generation of lazy entrepreneurs in Britain, capitalists who had no need to innovate or even become entrepreneurial because business was handed to them on a Tory silver platter. And those remaining urban managers no longer concerned themselves with redistributive justice; most wouldn’t even know what the phrase meant. Instead, their working day began to be passed applying cost-benefit analysis to calculate efficiency models, devising new business paradigms for delivering social services at minimum cost; services inevitably got contracted-out to low-ball bidders, and whole government departments were dissolved or replaced by new units of non-accountable “post-political” middle-managers, whose machinations are about as publicly transparent as mud. The Urban Question was rapidly becoming an old urban question.

Maybe what was most entrepreneurial about the 1980s was the innovative way in which the private sector reclaimed the public sector, used the public sector to prime the private pump, to subsidize the reproduction of capital rather than the reproduction of people. Any opposition was systematically and entrepreneurially seen off, done in, both materially and ideologically. In 1986, Thatcher abolished a whole realm of regional government—the Metropolitan County Councils—at the same time as she bypassed municipal authorities (frequently Left and/or Labour-run) with a new species of urban growth machine: so-called quangos, alleged public-private partnerships, bodies like Urban Development Corporations (UDCs), which spearheaded London Docklands, as well as redevelopment of Liverpool’s deindustrialised waterfront. By this time, I’d gone up to Oxford to do a PhD with the famous Marxist geographer David Harvey, who suggested I summarily went back down to Liverpool, back to its ruins and ruination, back to talk to Militant, back to look the negative in the face and tarry with it.

I’ve been tarrying with negativity ever since, trying to convert it into something positive. Yet several decades on, after a lot of reading, a lot of talking and listening, after a lot of political hope and a fair bit of disillusionment, after a lot of wandering around the world, I finally got down to writing my own version of Urban Question, entitled, somewhat unoriginally, The New Urban Question. It’s a short, polemical book, a hopeful book that nonetheless tries to cover a lot of ground. It goes back to the source in order to move through and beyond the times, our times right now, when any “Marxist approach” to the urban question demands hard answers; not least because now the dialectic of the urban as a site of capital accumulation and social struggle has changed.

As the Thatcherite 1980s gave way to the Blairite late-’90s, and as it stands today, extended reproduction of capital is achieved through financialisation and dispossession, through dispossession and reconfiguration of urban space. The urban is no longer an arena where value is created so much as extracted, gouged out of the common coffers, appropriated as monopoly rents and merchants’ profits, as shareholder dividends and interest payments; the urban, nowadays, is itself exchange value. We’re essentially moving from Castells’ 1970s era, when the urban found its definition as a spatial unit of collective consumption, to our era when the urban gets defined by new forms of predatory dispossession, by what I call, in The New Urban Question, “the parasitic mode of urbanization.”

Now, insofar as capitalist risk management goes, insofar as addressing glitches within the overall reproduction of capital in the economy, the state is a first line of defense, a veritable executive committee for managing the common affairs of a bourgeoisie and aristocratic super-elite, stepping in at the first signs of crisis—baling out the bankrupted corporations, the too-big-to-fail financial institutions. One way it gets away with it is through “austerity governance,” the latest form of ruling class manufactured consent, something fitting neatly with the material needs of those in state and economic power—the two are largely inseparable. Austerity enables parasitic predilections to flourish by opening up hitherto closed market niches; it lets primitive accumulation continue apace, condoning the flogging off of public sector assets, the free giveaways of land and public infrastructure, the privatizations, etc., all done in the name of cost control, of supposedly trimming bloated public budgets. What were once untouchable, non-negotiable collective use-values are now fair game for re-commodification, for snapping up cheaply only to resell at colossally dearer prices.

The net result, thirty years since my initial encounter with The Urban Question, is that collective consumption items have morphed into individualized consumption items. By that I mean as the state has divested from its apparent systemic requirement to subsidize and fund public goods, as it has divested from its role of ensuring extended social reproduction, erstwhile public goods have become accessible to people only via the market, hence at a price. Thus people themselves willy-nilly pick up the tab of the price of social reproduction; we’ve taken care of our own lot, in other words, often achieved it through borrowing money, self-reproducing as the private sector cashes in, quite literally at our expense. Returning, then, to the Castellian conundrum of how is it possible that the state can back away from funding collective consumption whilst ensuring the capitalist system continues to survive, we can answer it quite bluntly: via a debt economy.

According to a Bank of England report (November 2013), household debt in Britain has soared to record levels. Individuals now owe a total of £1.43 trillion. Families, we hear, are borrowing if only to deal with higher costs of living, using credit finance to pay household bills. The bulk of the debt is in mortgages, needless to say, which are steadily on the up, reflective of inflated house prices. The debt economy flourishes, both in public and privately, because it is at once profitable on supply and demand sides. On the one hand, cities experience budget cuts, workers get laid off, services cut, libraries and sports centers close, education funding is slashed; public facilities are sold off to private, for-profit interests, for-profit vultures who valorise knockdown price public infrastructure. Municipalities need to borrow money in order to raise money. Public services are then run and maintained by private interests, by capitalistic vultures, invariably declining in quality afterwards. On the other hand, people are compelled to pay more, more on council tax, more on education, more on healthcare, more on services that are now driven by accountancy exigencies rather peoples’ real needs. It’s no coincidence, then, that all those major items of collective consumption that Castells identified in the 1970s—education, housing, and health—are now items featuring on the ever-growing list of household debt burden. People are falling prey to predatory loan sharks to fund basic human needs.

Little wonder, too, that now there’s an emergent debt resistors’ movement gathering steam. Citizens on both sides of the Atlantic are striking out at the “Creditocracy” (Andrew Ross’s term) in our midst. They’re participating in a debtors’ movement, like “Rolling Jubilee” (rollingjubilee.org and jubileedebt.org.uk). In the US, Occupy Wall Street’s roving “Strike Debt” group hasn’t just waged war on the debt collector (college tuition debt alone in the US stands at $1 trillion); it has likewise baled out the people, raising $600,000 to buy back a cool $15 millions’ worth of household debt, at a bargain price on the secondary debt market, a lot emerging from sub-prime mortgage foreclosures. Rolling Jubilee has thereby liberated debt at the same time as highlighted the grand larceny and absurdity of our burgeoning debt economy.

Meantime, as governments insist on belt-tightening austerity policies, they turn a blind eye on tax dodging companies and super-rich individuals, who carve themselves up and re-register their head offices in tax havens like the Cayman Islands, Monaco or Luxembourg. Already, in response, a groundswell of opposition has developed. Grassroots organizations like “UK Uncut” have adopted rambunctious and brilliantly innovative direct action “occupations,” creating scandals around tax-avoiding parasites like the elite London department store Fortnum & Mason and Vodafone (who had a handy 0% income tax rate for 2012). UK Uncut have likewise launched concerted campaigns against HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland, Barclay’s and other Dodge City banks and financial institutions. Google and Amazon, too, lurk in the invisible wings, tax dodging and double-dutching all the way to the bank, awaiting popular ambush.

In this sense, tax reform and stamping down on bigwig tax avoidance might not be so reformist: it could even be revolutionary, kick-starting militant activism, a renewed urban politics based around the practices and conditions of indebted everyday life. Here, maybe the greatest reform and strongest prophylactic against parasitic urban invasion and dispossession is democracy, a strengthening of participatory democracy in the face of too much representative democracy, especially when representation is made by public servants intent on defending private gain. Public representatives simply shouldn’t have any legitimacy if they habitually let tax dodgers off the hook: We cannot accept their office.

Active citizens need to engineer some planned shrinkage of the financial sector, waging war on monetary blood sucking much as ruling classes waged war on public services during the 1970s and 1980s. In 1976, then-New York City Housing Commissioner Roger Starr said the city, any city, needed to separate out neighborhoods that were “productive” and “unproductive” on the tax base. His plan was to eliminate the unproductive ones, closing down the fire stations, police and sanitation services. Poor areas like the South Bronx suffered immeasurably. Ironically, the idea retains a good deal of purchase. Shrinking services that are unproductive drags on our tax base might boil down to financial services; and unproductive neighborhoods, drags our tax base, like London’s Mayfair, home of hedge funds and private equity companies, discreet behind iron-railed Victorian mews, spotlessly painted white, might be the first to be reclaimed.

Analytically and ideologically, the whole question of “managers,” especially of middle management, remains vital for pinpointing administrative culpability; or, if you will, is politically vital for breaking the “weakest link” in parasitic capitalism, To that degree, struggling for democracy means loosening the diktat these anonymous, unaccountable, behind-closed-doors middle managers have over our culture, those in the private and public sectors, those bankers and functionaries, technocrats and creditocrats who orchestrate the repossession of society. Breaking this weakest link implies struggling not only against the massively complex and alienating divisions of labor we have today, but also against the even more massively alienating bureaucratic compartmentalisations that rule over us, those precisely orchestrated by middle-managers and accountants who mediate between us and the 1%. To frame it that way is to suggest that middle managers remain central to a new urban question, to a new democratic problematic in which politicians and their administrators (or is that the other way around?) no longer even pretend to want to change anything significant.

Reblogged this on urbanculturalstudies.

LikeLike