“If you ride around on the subway with Jack,” Kerouac’s friend “Davey” Amram remembered, “or just go out on the street, he would talk to everybody, be natural and real with anybody.” “We used to walk around New York’s streets for hours,” said Amram. “One time we were hanging out with Allen Ginsberg, and there was a guy we met on the Bowery. He was a full-time wino named Buddy.” They all decided to go to Allen’s place with Buddy, and read poems. “I just listened,” Amram said.

They sat up all night. Ginsberg read his poems and Buddy, supping wine, would say, “Yeah, that’s pretty nice. I can dig that.” Then Kerouac read out his own and “Buddy would flip out and scream with laughter and slap his knee…he liked Allen’s poems, but he really identified with Jack’s. And Jack said, real quietly while Allen was reading a poem, ‘These guys are where I get so much inspiration from and learn so much from. They are the true poets of the streets’.” [1]

When Kerouac starred on Steve Allen’s Plymouth Show in 1959, the host asked Jack “How would you define the word ‘Beat’?” Kerouac didn’t hesitate in his response to Allen, saying, shyly yet assertively, “sympathetic.” He wasn’t being frivolous; Kerouac meant it and we can hear this sympathy resonating in his long blues prose poems, like Bowery Blues, dated March 29, 1955.

The Bowery was one New York landmark that captivated Kerouac and the Beats in their gnostic search for human truth. (Burroughs lived at number 222 in the mid-1960s, in a windowless apartment he called “the bunker,” really an old locker room of the former YMCA building.) For most of the twentieth-century, the strip, running from Third Avenue at East 6th Street and Cooper Square, down to Canal Street in Chinatown, was America’s most notorious skid row. Its flophouses and bars and sidewalks literally flagged out the end of the road for many denizens, a final port of call for the castoffs and casualties of Great America. It was an eternal source of attraction and repulsion for Kerouac, of sorrow and pity, and if we listen to the Bowery Blues in Poetry for the Beat Generation we can feel that pathos, as well as the compassionate embrace, for Bowery bums and winos, for lost souls like Jack’s buddy Buddy.

Interestingly, there’s a wonderful cinematic document of the Bowery from Kerouac’s time called On the Bowery, produced the same year as On the Road (1957), by indie filmmaker Lionel Rogosin. It’s a peculiar documentary, one part actual footage of the winos and bums and rag and bone men of what the Bowery’s own Mission Minister said was “the saddest and maddest street in the world and that might be an understatement”; many of the most vagrant vagrants we see carted off in a police paddy-wagon; they’re better off behind bars.

Yet the other part of Rogosin’s film is overlaid with performing actors, like Ray, from Kentucky, a dead ringer for Neal Cassady, who even worked the railroad before his luck ran out and he hit the bottle. Ray befriends Doc Gorman, once a genuine doctor but now a wily street veteran, an old rogue who scams his way through life, preying off the likes of Ray in dive bars and crummy SRO hotels.

The other looming presence, casting a dark shadow across much On the Bowery, is the overhead El, then in the process of being torn down, a redundant giant somehow adding further grit to Rogosin’s already gritty camera, as it pans images of real streets and real soup kitchens with real human flotsam and jetsam. At the end of On the Bowery, one old crony muses, watching Ray bidding them all a “final” goodbye, “Everybody tries to get off the Bowery.” To which his pal, shaking his head knowingly, adds “He’ll be back!”

“LATE COLD MARCH AFTERNOON,” Kerouac begins Bowery Blues, “the street (Third Avenue) is cobbled, cold, desolate with trolley tracks.” He’s sitting in the Cooper Union cafeteria, in its “Foundation Building” at Cooper Square, composing his poem, penciling impressionistic lines against a muzak, which, he says, is “too sod.” It’s an overcast, chilly, melancholic day, and Jack seems to feel the melancholy in his bones, gazing out the window on to Third Avenue, observing “cold clowns in the moment horror of the world.”

In those days, pretty much anybody could wander in and out of Cooper Union, an arts and science institution founded in 1859 by wealthy New York industrialist and philanthropist Peter Cooper. Cooper was prominent in the Gilded Age, an anti-slavery liberal progressive, a fervent believer that education should be free and open to all. Since inception, Cooper Union was intended to be an East and West Village community resource; its library and cafeteria were open late so working folk could eat and borrow books after hours, when their day’s toil was done. Cooper Union’s shibboleth back then was that every accepted student be granted a full-tuition scholarship.

Over the years, Cooper Union formed three Art, Architecture and Engineering Schools, though in 2014 it abandoned its long legacy of free education. These days, Cooper Square is dominated by the main campus building, at number 41, a controversial glitzy post-modern, deconstructed structure, costing 100 million dollars, accelerating the gentrification of the neighbourhood. Melancholy Beatsters, scribbling poetry in pencil, aren’t very conspicuous anymore.

“A funny bum with no sense trys to panhandle,” writes Kerouac in Bowery Blues, “and is waved away stumbling,/he doesnt care about society women embarrassed with paper bags on sidewalks—Unutterably sad the broken winter shattered face of a man passing in the bleak ripple.” “I shudder as at the touch of cold stone to think of him,” says Kerouac, “the sickened old awfulness of it like slats of wood wall in an old brewery truck.”

The same broken humanity that occupies Rogosin’s frame populates Keroauc’s prose: seafarers who’ve jumped ship, “bleeding bloody seamen…/sad adventurers/Far from the pipe/Of Liverpool…/Streaked with wine sop”; others “who’ve lost their pickles on Orchard Street”; and “old Irishmen/With untenable dignity/beer bellying home…/Paddy McGilligan/Muttering in the street…/Sad Jewish respectable/rag men with trucks.” The whole damned lot “with tired hope/Hope O hope/O Bowery of Hopes!”

“The story of man,” Kerouac says, “Makes me sick/Inside, outside,/I dont know why/Something so conditional/And all talk/Should hurt me so.” “And I see Shadows/Dancing into Doom…God bless & sing for them/As I can not.” “Then it’s goodbye/ Sangsara/For me,” he writes in the concluding stanza. Sangsara is the Buddhist cycle of birth and death, the continuous wheel of suffering. Does Jack want to give up and die that cold March day? It appears so. “Okay./Quit,” he says. But he doesn’t quit. Instead, Sangsara is his epiphany, his insight into life’s impermanence, into the reality of his “non-self,” revealed to him on the Bowery: “He’ll be back!”

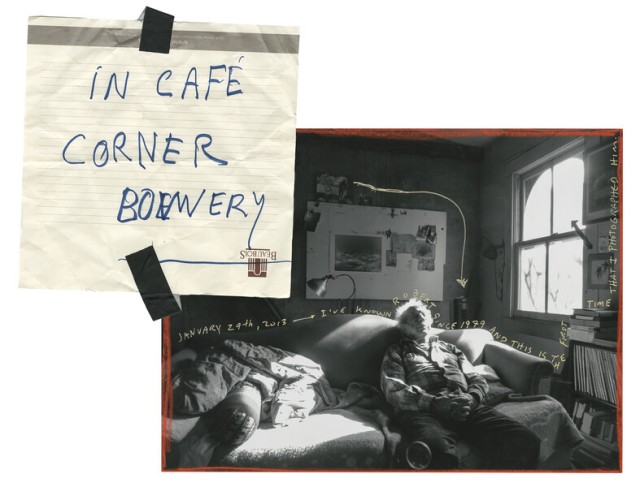

The strangest thing about the Bowery was that it was an area of New York that successive artists and writers dug most of all, finding creative stimulation amongst the human commiseration. Amid the grunge and desolation, a ragged community of dislocated and creative odd-balls discovered a certain liberty. A big attraction, needless to say, was the neighbourhood’s cheapness. Artists undertook quasi-legal rehabs of former Bowery industrial lofts, giving them work and living space at relative low cost. Jack’s photographer friend Robert Frank loved the Bowery and set up home and shop there in 1968, at number 184. (In 1980, he moved around the corner, onto Bleecker Street. By then, though, as rents began to soar, he and artist wife June Leaf spent most of their time up in Nova Scotia.) [2]

But it wasn’t just the low-cost that enticed. When Albert Camus came to town in 1946, like Sartre and de Beauvoir the year prior, it was the Bowery he wanted to see first: “Night on the Bowery,” Camus wrote in his journal, “Poverty—and a European wants to say: ‘Finally, reality’.” Sammy’s Bowery Follies, at 267 Bowery—a self-avowed “alcoholic haven” since 1934—was one venue Camus particularly adored and spent time in, drinking and mixing with Bowery bums; at Sammy’s, whose last orders came in 1970, vaudeville really required no stage. On the Bowery, bare life lurked, existentialism was on the street, expressed itself in dive bar banter, especially after dark.

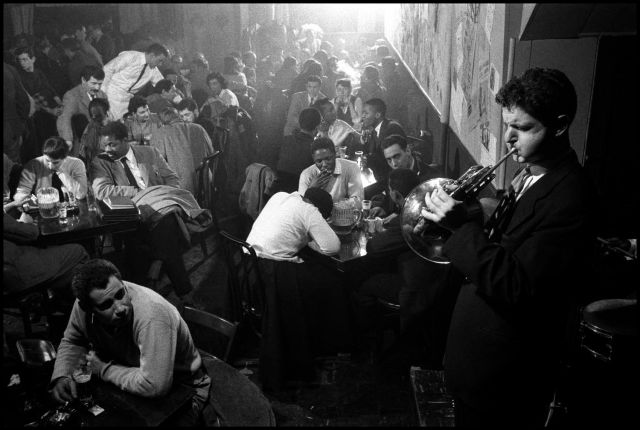

One of the city’s best jazz-joints, the Five Spot Café, likewise found cheap haven for awhile on the Bowery, between 4th and 5th Streets, staging jam sessions with jazz’s greatest—like Bird, Monk, Mingus, Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman, who’d just transplanted himself from the West Coast. It was one of Burt Glinn’s favourites venues to photograph. Here’s his luscious shot of Davey Amram blowing his French horn, before the Five Spot’s racially-mixed audience, a minor miracle in the 1950s.

JACK’S OTHER GREAT HYMN to pavement pathos and hobo rags is MacDougal Street Blues, penciled June 26, 1955. Its three “Cantos” embody almost all Beat street sensibility and wisdom. Kerouac’s street becomes something transcendental, a world-beyond, a wild wilderness for Bodhisattva meditation. It’s a shifting scene full of sidewalk strollers eating ice cream on a lovely June Sunday afternoon, struggling Greenwich Village artists selling their wares, eccentric winos and chessmen of Washington Square, homeless bums panhandling and old bohemian barflies, like the legendary Joe Gould, holding court in the Minetta Tavern, corner of MacDougal and Minetta Lane. All the while, overhead, Kerouac says, “is a perfect blue emptiness of the sky.”

The goofy foolish

human parade

Passing on Sunday

art streets

Of Greenwich Village

…

Slow shuffling

art-ers of Washington Sq

Passing what they think

Is a happy June afternoon

Good God the Sorrow

They don’t even listen to me when

I try to tell them they will die

…

Unrepresented on the iron fence

Of bald artists

With black berets

Passing by

One moment less than this

Is future Nothingness Already

The Chess men are silent, assembling

Ready for funny war—

Voices of Washington Sq Blues

Rise to my Bodhisattva Poem

Window

…

Parading among Images

Images Images Looking

Looking—

And everybody’s turning around

& pointing—

Nobody looks up

And In

Nor listens to Samantabhadra’s

Unceasing Compassion

…

Why are you so tragic & gloomy?

And on the corner at the

Pony Stables

Of Sixth Ave & 4th

Sits Bodhisattva Meditating

In Hobo Rags

Praying at Joe Gould’s chair

For the Emancipation

Of the shufflers passing by

Joe Gould was one of the most infamous Village street shufflers, immortalised in Kerouac’s early New York days by New Yorker reporter Joseph Mitchell. In 1942, Mitchell had written his celebrated profile of Gould—“Professor Sea Gull”—and one can speculate whether Kerouac had ever read this piece. Mitchell was of an older generation, a Village denizen himself, a street-smart journalist, who, like Kerouac, was an intrepid urban legman, with sympathies for the downtrodden. His New Yorker “Profiles” were the last time the Condé Nast magazine would ever write about poor, ordinary, non-celebrity people. Mitchell did so with considerable literary dash. (His great hero was James Joyce.) Joe Gould became Joe Mitchell’s masterwork; and “the penniless and unemployable little man” even became a kind of alter-ego for Mitchell.

Gould, wrote Mitchell, “came to the city in 1916 and ducked and dodged and held on as hard as he could for over thirty-five years.” He “looked like a bum and lived like a bum. He wore castoff clothes, and he slept in flophouses or in the cheapest rooms in cheap hotels. Sometimes he slept in doorways. He spent most of his time hanging out in diners and cafeterias and barrooms in the Village or wandering around the streets or looking up friends and acquaintances all over town or sitting in public libraries scribbling in dime-store composition books.” For years, Gould said he was at work on his epic masterpiece, “An Oral History of Our Time,” and for that he was always on the cadge for money, for contributions towards “The Joe Gould Fund.” Gould said this was his life’s endeavour, going about the city listening to people, eavesdropping, and writing down whatever he heard that sounded revealing, no matter how idiotic, obscene or trivial it might be to others.

He claimed he’d already amassed millions of words in this Oral History, filled hundreds of composition books, scattered all around town, hoarded for safe-keeping by assorted friends. He bragged it was a study of modern America as historically important as Gibbon’s treatise on ancient Rome. Yet before Gould died, in 1957, of arteriosclerosis and senility, aged sixty-eight, Mitchell came to recognise something he’d long suspected: the Oral history didn’t exist, had never existed. Gould’s entire oeuvre amounted to just a few bad poems, a “chapter” on the death of his father—written, rewritten and revised over and over again—together with a gibberish disquisition on how tomato consumption spread a disease Gould called “solanacomania.” But that was all. Nothing else. He’d duped everybody, Mitchell included.

In 1964, more than twenty-years after his first assignment, Mitchell completed a second and longer New Yorker piece about this enigmatic little man—“Joe Gould’s Secret”—revealing the awful truth. [3] At the same time, Mitchell anticipated his own awful truth, his own secret, finishing his article with a confession: he’d been at work on his own version of Gould’s oral history, a Bildungsroman novel, autobiographical, about a young man coming up from North Carolina to conquer New York’s reporting world, a man who falls in love with a woman and with a city. This man would poke around every one of city’s hundreds of neighbourhoods, in a soul searching mission, a quest for self-discovery, not in “the lofty, noble silvery vertical city but in the vast, spread-out, sooty-grey and sooty-brown and sooty-red and sooty-pink horizontal city; the snarled-up and smouldering city, the old, polluted, betrayed, and sure-to-be-torn-down-any-time-now city.”

Mitchell had provided a disguised synopsis of a promised book, a book he’d never write, seemingly couldn’t write. Meanwhile, his 1964 profile, revisiting Gould, was valedictory, the last thing Mitchell wrote. Up until his death in 1996, Mitchell came almost every day to his New Yorker office, typed away, immaculately attired as ever, in collar and tie and trademark hat, yet produced nothing more, no more Profiles, no novel, not anything. What had he been typing away at all those years? Nobody knows.

SOMETIMES, WHENEVER MITCHELL received mail addressed to Joe Gould, he’d forward it to the Minetta Tavern, Gould’s home away from home. [4] There, each evening, the Village vagrant got a free spaghetti and meatballs dinner, made from leftovers, his sole meal of the day. In an unspoken agreement with the proprietor, he was the “authentic” house bohemian; and clientele usually bought Gould a glass of wine or a beer or a martini. His best-known antic was imitating the flight of a seagull, hopping and skipping and leaping and lurching about, flapping his arms up and down and cawing like the sea bird. He claimed he’d long ago mastered the language of seagulls, learned it in boyhood, when he spent hours sitting at Boston harbour.

One time Mitchell received a letter from a neighbourhood artist called Sarah Ostrowsky Berman, warning of how Gould was “in bad shape.” The writer said she felt “the city’s unconscious may be trying to speak to us through Gould. And that the people who have gone underground in the city may be trying to speak to us through him. People who never belonged anyplace from the beginning. Poor old men and women sitting on park benches, hurt and bitter and crazy—the ones who never got their share, the ones were always left out, the ones who were never asked.” Perhaps the Beats, too, had heard this city’s unconscious speaking out—Kerouac hadn’t called his crew the subterraneans for nothing, once saying homeless underground people had good reason to cry, for everything in the world is stacked against them.

Kerouac had written movingly about homelessness in his debut novel, The Town and the City (1950), an adolescent Bildungsroman the likes of which Mitchell couldn’t quite pull off, where alter-ego Peter Martin attempts to exorcise ghosts of his small town past in Galloway (Lowell), only to have to confront the equally troubling demons of big city (New York). One raw Sunday afternoon in winter, Peter finds himself on the Bowery, “when the cold ruddy light of the sun was falling on dusty windows and streaming through El girders black with soot, he saw three old men, old Bowery bums, lying on the pavement against a wall trying to sleep, on newspapers.”

He stops to look at them. “They looked dead,” Peter says, “but then they stirred and groaned and turned over, just like men do in bed, and they were not dead. He thought of what must have happened to them that they slept on the pavements of November, and that their only belongings in the world were the filthy clothes that covered them. It also flashed through his mind that they were old men as well, rheumy-eyed, sorrowful, sixty or so, shaking with palsy, fixed against the weathers and miseries as though driven through with a spike, sprawled there for good. He had to walk away, he cried.”

Around the time Peter cried, his creator heard in person the city’s unconscious speaking out through Gould, knowing Professor Seagull’s notoriety first-hand; Burroughs also remembers witnessing Gould’s seagull act. Indeed, not long after Mitchell’s profile first appeared in The New Yorker, both Kerouac and Burroughs had Gould cameo in their jointly-written novel And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. That was in 1944, and the Minetta Tavern was then their local hang out; Gould’s Village was similarly the Village of Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs. It was likewise the Village of their mutual friends, Lucien Carr and David Kammerer, the two principal characters—real-life characters—fictionalised in And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. In August 1944, a nineteen-year-old Carr had stabbed to death Kammerer, fourteen-years his senior, in Riverside Park on the Upper West Side, dumping the body in the Hudson. It was front-page news, an older-guy-stalker impulsively killed by a younger victim in a drunken quarrel.

In those days, Kerouac and Burroughs were unpublished unknowns; the former had yet to go on the road and the latter’s drug habit was still soft. For decades their novel remained unpublished, the manuscript even thought lost. But it resurfaced, eventually getting published in 2008, with chapters sequentially written by Mike Ryko (Kerouac) and Will Dennison (Burroughs), in a remarkable recreation of wartime bohemian New York, a sort of Beat pre-history, Beatnik life and times avant la lettre. And there, in all his mad, eccentric glory is Gould, too, whose table at Minetta’s Ryko, Dennison and their girlfriends often shared. They said they frequently had “a good time listening to Joe Gould and basking in the suggestive dialogue around him.” Sporting his cane, Gould sometimes followed them to parties, participated in their haphazard drinking and drifting, in their talk-ins and poetic excess.

Today, everything here, Mitchell’s stories included, sound like period pieces, a tale of another era when Gould-like eccentrics, urban cast-offs and subterraneans found a little space to exist in the city. It was an era when they were tolerated and occasionally encouraged, when they had some underground as well as a few overground haunts to roam in, their own secret language-game, muttering the city’s unconscious. Gould had its history in his head. The Beats spent the following decades trying to transcribe those words on the page, in poetry and prose. If there was a singular impulse, perhaps we can think of it as a body of work dedicated to the emancipation of street shufflers who once passed by—passed by before they were chased away.

NOTES

[1] I’m citing Amram from the wonderful testimonies of Jack’s Book (1978), compiled by Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee. David Amram is still with us today, ninety this year, and well-known as a composer and conductor of orchestral and chamber works, many bearing a distinctive jazzy penchant. In his early Beat days, he wrote the musical score for Frank’s Pull My Daisy, and was a young sideman (French horn) for Thelonious Monk and other jazz stars. Later, Amram composed film soundtracks and worked with the New York Philharmonic as a composer-in-residence. In 2002, his Beat remembrance, Offbeat: Collaborating with Kerouac, appeared, followed five years on by Upbeat: The Nine Lives of a Musical Cat. Amram’s other claim to fame was to appear with Kerouac (and Philip Lamantia and Howard Hart) at New York’s first ever jazz poetry reading, at the Brata Art Gallery on East 10th Street. The historic event was organised by poet Frank O’Hara, who’d later achieve notoriety with Lunch Poems, published by City Lights in 1964.

[2] Kerouac and Frank, just two years apart in age, were like two peas in pod, outsiders both, with roaming “eyes” for “American-ness”; the former, of French-Canadian extract, the latter, a Swiss-born immigrant. When Kerouac wrote, in his famous introduction to Frank’s The Americans, that “after seeing [Frank’s] pictures you end up finally not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin,” you could say much the same thing about Kerouac’s prose. In April 1958, he and Frank undertook their own road trip together, from NYC to Florida, described in Kerouac’s essay “On the Road to Florida.” “It’s pretty amazing,” Kerouac said, “to see a guy, while steering at the wheel, suddenly raise his little 300-dollar German camera with one hand and snap something that’s on the move in front of him, and through an unwashed windshield at that.” After awhile, “I suddenly realised I was taking a trip with a genuine artist and that he was expressing himself in an art-form that was not unlike my own.”

[3] Joe Gould’s Secret became a film in 2000, staring Stanley Tucci as Mitchell and Ian Holm as Gould. The atmosphere of Greenwich Village in the 1940s is beautifully evoked, yet the movie only scratches the surface of the deep and complex psychologies of both Joes.

[4] Minetta Tavern first opened its doors in 1937 and lives on—though is much less rougher around the edges, reinventing itself in 2009, to attract a more upmarket and tonier crowd. The tavern’s website says, “Since its renovation, Minetta Tavern has best been described as ‘Parisian steakhouse meets classic New York Tavern’.” “The Tavern,” the site continues, “was frequented by various layabouts and hangers-on including Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, Eugene O’Neill, e. e. Cummings, Dylan Thomas, and Joe Gould, as well as by various writers, poets, and pugilists.” Yet at $22 for a glass of Chardonnay, and $33 for a “Black Label” prime- cut beef burger, the only layabouts and hangers-on these days ascend from Wall Street.

Great work, Andy, my brains are awash down the side of the blue orange table!

LikeLike

Greeat post thanks

LikeLike