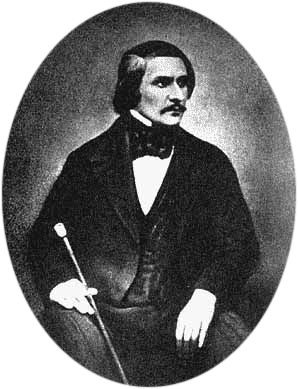

It’s a bright, remarkably mild, late-January morning. I’m standing on the shady side of the street near Piazza Barbarini, in the heart of Rome’s commercial district, looking at the sun strike Via Sistina, number 125. The Ukrainian-born scribe, Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852), lived on the top floor of this handsome five-story sandstone building. A commemorative plaque on its outside wall has a familiar profile of the writer, with his famous beak-like nose, and an inscription: IN QUESTA CASA DOVE ABITÒ DAL 1838 AL 1842 — PENSÒ E SCRISSE — Il SUO CAPOLAVORO. In this house lived Gogol, from 1838 to 1842. He thought and wrote his masterpiece. Gogol first arrived in Rome on March 26, 1837, and for the next decade, on and off, the Italian capital became his beloved home away from home. In this very apartment, he wrote the bulk of Part 1 of Dead Souls, his unfinished epic “prose poem” to old Russia.

At street level, near the building’s doorbells, there’s another, smaller plaque, in gold, with another profile of the writer, looking the dapper dandy we know him to be. The plaque, Casa di N.V. Gogol, implies his apartment is now a little museum open for visits by appointment only, something I’ll follow up on another day.

Via Sistina is a narrow artery that climbs steadily a quarter of a mile to the top of the Spanish Steps, lined today with an array of trinketry tourist stores, restaurants, shoe shops, jewelers, and a theater. From here you get an impressive, uninterrupted, straight-line view of Piazza della Trinità dei Monti, with its fifteenth-century renaissance church and imitation Egyptian obelisk—Obelisco Sallustiano—constructed in the early part of the Roman Empire. Gogol knew Trinità church well, would have entered it many times, doubtless prayed in it, walked by it most days on his way to Villa Borghese, one of his favorite Roman stomping grounds.

I stroll up Via Sistina, absorbed in Gogol’s Rome, thinking about the letters I’d been reading lately, where he’d waxed lyrical, sometimes ecstatically, about the Eternal City: “I have never felt so immersed in such peaceful bliss,” he wrote on February 2, 1838. “Oh, Rome, Rome! Oh, Italy! Whose hand will tear me away from here?” Looking up at Via Sistina this glorious morning, at the brilliant blue sky, I understand another effusive Gogol dispatch from the spring of 1838: “How beautiful the blue patches of sky are now—between the trees barely covered with a fresh, almost yellow, greenery, and even cypresses, dark as a raven’s wing…What air!” “You ask me where I am going this summer,” he wrote his friend Alexander Danilevsky (April 23, 1838), “Nowhere, nowhere but Rome.”

An inveterate walker, Gogol journeyed on foot to Villa Borghese, up Via Sistina and onto Viale della Trinità dei Monti, often composing as he moved, dialoguing with himself, enacting aloud scenes from his writings. To the passerby, this diminutive man with shoulder-length, slicked-down locks and a daintily waxed moustache, tapping his walking stick–his “wanderer’s staff”–as he went, would have cut a decidedly weird figure. He looked like a cross between Charles Baudelaire, the Parisian poet-flâneur, and the mysterious “V” from V for Vendetta, the flamboyant action hero who, donned in Guy Fawkes mask, avenged political wrongdoers. (Gogol’s cheeks, too, occasionally bore the same hint of red blusher.) Gogol became legendary not only for his writings, but also for his strangeness: aloof and self-obsessed, insufferably hypochondriacal, friends and admirers forgave his erratic and unpredictable behavior, taking it as a symptom of genius.

I’d read a lot of Gogol in my time, knew about his idiosyncrasies, about his bizarreness; but never before had I associated him with Rome. And yet, now, I’m on a Roman Gogolian pilgrimage, toying with the idea of writing about his works, about him, about him and me in Rome, about my Gogol: not the reactionary religious zealot he became later in life, denouncing everything he’d hitherto written, all his liberal tendencies, all his brilliant Petersburg stories, in the awful Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends; nor, either, the pyromantic Gogol who tossed drafts of Part 2 of Dead Souls (five-years hard graft) into the fire, starving himself to death in the process. Plastered in blood-sucking leeches and dowsed with freezing cold water, Gogol’s end seemed to re-enact the agonizing and feverish climax of his own Diary of a Madman, art somehow mimicking life: “They’re pouring cold water over my head! What have I done to them? Why do they torture me so? My head is burning and everything is spinning round and round. Save me! Take me away!”

No, my Gogol is the comic wizard with a penchant for the “little man,” for the bullied and bludgeoned who invariably lose yet occasionally get revenge—though never, in Gogol’s hands, in any classic heroic sense. All Gogol’s heroes are anti-heroes. This is the Gogol who sniffed out phoniness and had it in for hypercritical liars, for important persons in authority, the Gogol who, in a letter (March 30, 1849), once said: “The words populism and nationalism are fashionable now, but so far these are just shouts which spin heads and blind the eyes” (Gogol’s emphases).

My Gogol is the brilliant creator, the engaged humorous admired by the likes of Marx (who, remember, in old age taught himself Russian and took pleasure reading his two favorites: Pushkin and Gogol); Antonio Gramsci (whose Prison Notebooks reference Village Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, stories narrated by a Ukrainian bee-keeper Panko, dear to the heart of the Sardinian native); Walter Benjamin and an Arcades Project fascinated by Gogol’s evocation of crowds; Marshall Berman, whose Gogol in All That is Solid Melts into Air presents “the special magical aura of the city at night”; and Guy Debord, who, in the late 1980s, urged himself to read and reread, in the following order, The Government Inspector, The Quarrel Between the Two Ivans, The Nevsky Prospect, and The Overcoat. Debord also liked to quote one of Gogol’s final, mysterious messages, found on a scrap of paper after his death: “Be a living soul, not a dead one.”

My Gogol, then, isn’t so much what Gogol was as what he is to me and what he can become for us today. I say this mindful of the fact that large swaths of his Ukrainian homeland, his “Little Russia,” the “bewitched places” evoked in early stories, now lie in rubble, destroyed by Russian forces. Mariupol, for instance, once a vibrant Ukrainian city, site of the annual Gogolfest, an internationally renowned arts and literary festival, honoring its literary patron saint, is these days described as “a tangled mess of crumpled buildings and a place of shallow graves.” Thousands of civilians have been killed during the fighting, and “Mariupol has suffered some of the worst destruction in war-scarred Ukraine.”

Meanwhile, Myrhorod, a small town of some 40,000 people, immortalized in Gogol’s short story collection, with classics like Old-World Landowners, Viy, and The Quarrel Between the Two Ivans, has been shelled by Russian missiles yet largely spared the most active warfare. It’s since become a regional hub for refugees fleeing their war-torn homes elsewhere in the Ukraine. What would Gogol have made of such conflict? Hard to say.

His tales of the bucolic charm of Ukrainian village life, with its fairs and songs, frequently feature not-too-charming drunken debauchery and the devilish machinations of witches, wizards, and demons. When Gogol’s Viy was put to film in 1967, it became the Soviet regime’s first gothic horror show, one of the scariest movies I’ve ever seen, up there alongside The Exorcist—spine-chillingly terrifying in its special effects about the most demonic of all demons, a massive humanoid creature, Viy, haunting the corpse of a beautiful young maiden. This is how Gogol saw life in his homeland: not straightforwardly happy-go-lucky; terror and the abyss are never far away…

I pass Trinità dei Monti church, retracing Gogol’s steps toward the Villa Borghese, walk by Villa Medicis. Despite the populism and nationalism still spinning people’s heads and blinding eyes, I’m grateful to be alive this fine morning, to be here in the sunshine, with Gogol. I’m even overheated, take off my scarf, stop off at Borghese’s expansive Piazzale Napoleone, to admire the sweeping vista over Western Rome. In luminous light, St. Peter’s dome hovers majestically in the near distance.

Ancient and modern Rome lies before me, the dead and ruined commingling with the living, with its rooftops and terraces, churches and statues, domes and bell-towers and collapsing walls—with a bustling humanity little changed since Gogol’s day. Gogol loved to immerse himself in Rome’s bustling humanity and took long walks that often finished up at the Vatican. Thereafter he’d lie on the dome’s interior cornice, near the base of its drum, marveling at Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, joking to friends about how he’d swapped one St. Peter—St. Petersburg—for another.

I navigate the myriad paths of Villa Borghese’s two-hundred-acre arcadian parkland, created in 1605 on Cardinal Borghese’s former vineyard, and stroll along a track beside the Casina del Lago, the “little house on the lake,” a café with a crowd sitting al fresco in the warmth. I go by the lake, watch tourists out on rented paddle boats, and head toward Gogol—toward, that is, a 2.8-meter-high bronze reincarnation of the man, oversized, tucked away under a Black Popular tree, just across the street from the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Gogol was a little man yet a giant among nineteenth-century authors. That’s maybe why his commemoration is so big, the creation of Georgian-Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli (1934- ). “A Master Ahead of His Time,” it’s called, erected in 2002, something not only massive but also aptly surreal. A booted and seated Gogol supports his head on his lap, a masquerade ball-mask of his own face, with that prominent snout, glancing slyly sideward, not a little playfully, unnervingly, a stare that’s the stuff of nightmares.

Here we have a two-faced Gogol, explained, perhaps, by the inscription on the monument’s base, an extract from an 1842 Gogol letter, in Russian and Italian: “I can write about Russia only in Rome. Only there does Russia stand before me in all its hugeness.” In looking at Rome, in living in it, in breathing in its air, only then, says Gogol, could he see Russia close up, feel and conceive the land in all its vastness. Russia and Rome were constantly on Gogol’s mind, hence the double vision, the existential schizophrenia. He needed warmth to write about cold, brightness to describe dreariness, vibrant metropolitan noise to convey dismal provincial quiet.

“I’ve lived for almost a year in an alien land,” he wrote his friend Mikhail Pogodin (March 30, 1837). “I see beautiful skies, a world rich in arts and man. But did my pen rise to describe things capable of striking anyone? I couldn’t devote a single line to what is alien…and I preferred our poor, our dim world, our smoky huts, the bare expanses, to the best skies which look down on me more amiably.” A few years later, he tells another friend Peter Pletnev (March 17, 1842), “In Rome I wrote in front of an open window, fanned by salubrious air which does wonders for me.” And then, seven-years on, another dispatch, this time to Count Tolstoy (August 20, 1849): “salubrious air and warmth which is not from a stove are essential to my mind and body, especially when I am working.”

But Rome’s torrid summer heat equally prompted some typically bizarre Gogolian reactions. In a letter to Danilevsky (May 16, 1838), he asks for help “picking out a wig for me.” Gogol wants to shave his head, he says, “not so that my hair will grow this time, but for my head itself, to see if it will help the perspiration and along with it the inspiration to come out more intensely. My inspiration is clogged up; my head is often covered in a heavy cloud which I have to try constantly to dissipate, and meanwhile there is so much that I still have to do. A new kind of wig which fits any head has been invented; they are made not with iron springs but with gum-elastic ones.”

All the same, Gogol did pen a piece about Rome, “a fragment,” he called it, about the fate and fortune of Rome and the Italian peoples—even if, we can surmise, it is the fate and fortune of the Russian peoples as much in mind. The fifty or so pages of Rome [Rim] are relatively insignificant in Gogol’s overall oeuvre. There’s little Wow! here, little storyline or character development. What we do get, though, is a sense of Gogol’s deep feelings for the city, his love affair with it, his romance with its bricks and mortar and culture.

Always intended as a longer work nowhere near completed, his “fragment” lacked something, even on its own terms; Gogol knew it, because, in 1842, when Pogodin published it in his new journal, The Muscovite, Gogol submitted it reluctantly, feeling pressured. He told his friend Sergei Aksakov (letter, March 13, 1841), “that he [Pogodin], if a Russian feeling love for the fatherland beats in his heart, he should not demand that I give him anything.”

Rome is uncharacteristically humorless, too overloaded with adjectives and adverbs, with hyperbole and elaborate descriptions that bury any semblance of plot. After a while, we recognize it’s Rome itself that’s the plot, that’s the subject and object of Gogol’s concern. The tale is cued by the introduction of a stunningly beautiful young woman called Annunziata, a Madonna whom we thought was set to be Gogol’s heroine, his metaphor for the city. Yet soon she fades from the scene, and attention shifts to the adventures of a twentysomething Roman prince, whose family has fallen on hard times; his father died with piled up debts, and the prince’s uncle bankrolls the young man’s sojourn in Paris, sending him off to study in the French capital.

He’s immediately smitten with a sparklingly modern Paris, a joyous contrast to the moldy backwardness of his homeland, encased in its dead past. Everything in the City of Light delights our prince, its art and culture, its crowds and street life, its hustle and bustle. Here is a city that moves, that’s alive, forward-looking. Gogol’s prose sometimes sounds like a chip off Baudelaire’s block, with his lyrical renderings of the Parisian phantasmagoria. For a few years, the prince is ecstatic, thrilled by his new environment, dazzlingly happy with his new life. But as time goes by, the razzle-dazzle of Paris begins to wear thin. Before long, his burning desire is to return to old Rome, to reconnect with what he once knew—or rather to see it again with fresh eyes, with more mature, reinvigorated eyes.

After a tearful homecoming, he delights with a city he was once saw as unworthy. What used to appall our prince now enchants him. Almost immediately “a majestic idea” comes to him, that a “higher instinct” prevails in Rome, that it hadn’t died but is irresistible; that it has “eternal domination over the whole world,” a “great genius floating over it,” a genius holding sway “by means of its very decrepitude and ruin.” The miracle of Rome is that it haunts like a living phantom. Rome isn’t dead, could never die: “in the very ruins and magnificent poverty there wasn’t that oppressive, penetrating feeling that involuntarily envelops a person who contemplates the monuments of a nation that has died while still alive. Here there was the opposite feeling; here was a luminous, solemn serenity.”

So speaks our prince and so, presumably, does our friend Gogol–our Niccolò, as Italians knew him. In the tale’s denouement, the prince gets tangled up in a crammed street carnival along Via del Corso, Rome’s principal north-south shopping thoroughfare, an Italian Nevsky Prospect. There, amid the throng, he glimpses Annunziata for the first time, the radiant image Gogol created at the beginning of his tale. “Looking at her,” our prince says, “it became clear why Italian poets compared beautiful women to the sun.” She was “a complete beauty,” a beauty that merits being seen by everyone. He sees her, yet… yet… jostled by the crowd, he just as quickly loses her. Is it love at last sight?

He struggles to free himself from the hordes of people, to find her, to follow her, to look at her again: who is she anyway? What’s her name? Where does she live? Where is she from? We’ll never find out. In pursuit, he crosses the Tiber, enters Trastevere, starts to climb toward Monteverde, when, all of a sudden, a marvelous panorama of the Eternal City, his Eternal City, opens up in front of him, a “whole bright heap of houses, churches, domes, and sharp spires powerfully illuminated by the brilliance of the sinking sun.” “My God,” he says aloud, “my God, what a view!” In awe of what he sees, “he forgets himself, forgets about the beauty of Annunziata, forgets about the mysterious fate of his people”—he even “forgets all else that exists in the world.” He’s found his great beauty, his grande bellezza, the great love of Gogol’s life. (In Paolo Sorrentino’s La grande bellezza, the Italian director’s 2013 cinematic homage to Rome, the film opens on a site where the prince likely stood, at the terrace facing the Fontana dell’Acqua Paola. Soundtracked by David Lang’s sacred I Lie, the breathtaking view that overcame our prince overcomes a Japanese tourist, who collapses and dies of a heart attack.)

***

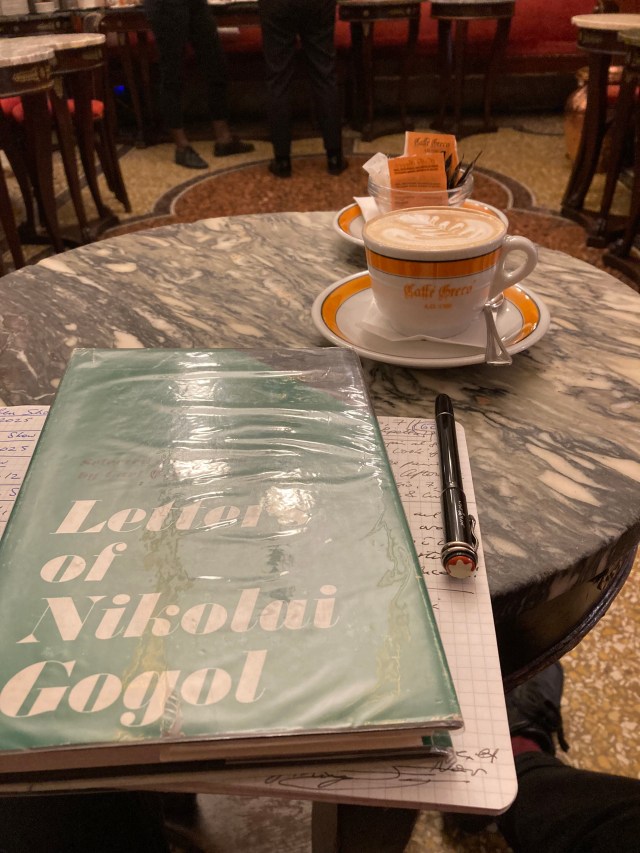

It’s a few days since my jaunt up Via Sistina and around Villa Borghese. I’m sipping cappuccino late Monday morning at the Caffè Greco along Via dei Condotti, one of Rome’s fanciest shopping streets. It’s another Gogolian favorite. Indeed, he had his preferred table here, popping over from his apartment, descending the Spanish Steps, onto the Piazza di Spagna, and making the minute or so stroll from the top of Condotti. It’s a quiet time to come. I’m sitting at one of the red velvet-covered benches, alone at a little table, listening to Mozart gently hum at just the right volume. There’s an oldie-worldly feel to the place, a hushed nineteenth-century elegance. The waiters and waitresses all wear black dress suits, and sport black and white bow ties.

I’ve a discrete corner to think about Gogol, to muse on what I want to write about him, about the works that mean so much to me, about his time in Rome, about my time in Rome pondering his time. Caffè Greco is like a surrogate art gallery with walls full of paintings and old photographs, memorabilia of its long history—Rome’s oldest café, established in 1760. Judging by the languages I hear spoken, the clientele is predominantly Italian and Russian tourists—well-heeled, prepared to fork out the 14 euros a small cappuccino set me back, the most expensive I’ve ever drunk anywhere, more expensive even than Paris’s Café de Flore.

Deep inside Caffè Greco, on a side wall, is a small commemoration to Gogol, a little rectangular plaque dating from 1902, in Russian, inaugurated at the fiftieth anniversary of writer’s death. In an alcove not far away, there’s a small, fascinating, easy to miss, oil painting of the man, sitting at a similar table to mine, drinking from the same type of coffee cup, surrounded by a host of friends, some wearing top hats. Gogol, hair neatly parted at one side, is turning toward the painter, wearing a natty white suit with a white starched high-collared shirt. How did the perennially hard-up, debt-ridden, Gogol afford such café society?

In his own lifetime, after all, he made no money from literature; and apart from a brief, lowly civil service post in his youth, and a disastrous (and equally brief) stint as a Medieval History lecturer at the University of St. Petersburg (1834-5), for which he had no qualifications or calling, Gogol never had any paid job. He was always broke and got by because of masterful freeloading, a long-practiced talent of converting loans into gifts. Looking at the lovely little oil painting of him now, it’s clear that one of the mates around Gogol’s court would have picked up the tab.

Upon closer inspection, it appears the picture here wasn’t posed for in Gogol’s age, but is in fact a relatively recent affair, a twentieth-century creation, painted in 1969 and signed off in red ink by a Russian artist called Bocharov (his first name in the bottom right of the canvas is indecipherable). One assumes it was based on solid historical evidence, on where Gogol sat, on how he dressed, with accurate details of Caffè Greco’s interiors, circa 1840.

Other images of Caffè Greco suggest that today’s décor and furniture look pretty much like yesteryears. The whole ambience feels the same as the Gogol painting’s. Where was the writer sitting, I wonder, at which table? Which one was his fav? When I order another cappuccino, I ask the waiter if I can move to the table that had just become vacant, right under Gogol’s canvas. I tell him, in my awkward Italian, I want to be near Gogol. The waiter says that Gogol’s table, the one he’s at in the painting, his preferred, is actually over there, nearer the entrance to the café’s seating area. The waiter explains, pointing, that the large canvas in Gogol’s picture is that one there, of Venice, on the other side of the column. I’m grateful for the clarification, ask if I can move again, to Gogol’s table, thrilled to reposition myself at his pew.

With me is a book of Letters of Nikolai Gogol, edited in the 1960s by Carl Proffer, a tatty University of Michigan Press hardback that I’m slowly working my way through, trying to get a better picture of the man inside the works. One letter, from September 1839, describes Gogol’s method of composition: “it’s strange,” he says, “I am not able to work when I am devoted to seclusion, when I have no one to chat with…I was always amazed at Pushkin who had to take himself off to the country alone and lock himself up in order to write. On the contrary, I could never do anything in the country; and in general I cannot do anything where I am alone and where I experience boredom…the more gaily I spend the eve before, the more inspired I was returning home and the fresher I was in the morning.”

A lot of Gogol’s letters have him on the cadge for money or complain about his ailments, about his constipation and diarrhoea, about his poverty, chiding his friends for abandoning him, for misunderstanding him; he promises to pay them back the money he owes, if only he could. (In the early 1840s, Gogol is reputed to have amassed debts exceeding 18,000 rubles.) Some letters pour his heart out about Dead Souls, his struggles to write it, his run-ins with the Russian censors, about how this work sustains him, makes him happy; he’s unhappy when not writing.

Other letters are to his mother and sisters, giving them a ticking off because they worry about him traveling too much; why can’t he be a good boy, they ask, and come home to settle in Moscow? He, in turn, gives them a ticking off for mismanaging their financial affairs, for not really knowing who he is. Many later letters express Gogol’s deepening religiosity, his divine calling as a writer, as a prophet. In very few letters does he come across as a nice human being. One, to Pogodin (December 28, 1840), has him trying to exonerate his behavior: “Oh! You should know that he who is created to create in the depth of his soul, to live and breathe his creations, must be strange in many respects…How painful it is sometimes.”

Gogol clearly needed people, friends, around him, those who tolerated him; he was gregarious in his introversion. So it’s not surprising to see him sitting with an entourage, surrounded by friends. He was perhaps a typical artistic émigré in Rome, living not far away from where, two decades earlier, Keats and Shelley had lived, holding a similar romantic disposition toward his adopted city; a typical artistic émigré in the sense of willfully choosing displacement, of having the privilege of self-imposed exile. Gogol wandered around a lot of Europe before he found Rome, bivouacking in Lübeck, Hamburg, Baden-Baden, Geneva, Paris, Vienna, among other places. Still, no matter where he went, he’d always remain very Russian, seeking a society of his compatriots; in Rome, his circle of friends and acquaintances was fairly large, yet he wasn’t, despite speaking good Italian, intimate with any Italian.

The happiness he tasted in Rome derived precisely from this sense of displacement, of being Russian anywhere, everywhere, a fugitive Russian, a Little Russian. For someone of Gogol’s personality, if he’d put down roots in Italy, established the same deep connection he had with his native soil, even attempted to, he’d have likely finished up hating the place; Rome would have become something real, like Russia, no longer a mythical paradise of the imagination, no more the place where he felt exotic dislocation.

Sitting in the Caffè Greco, looking around me, at everything exotically strange yet captivating, I begin to understand the privilege of my own displacement, related somehow to Gogol’s. Sort of. I never dreamed of living in Rome (that dream was always of New York), never dreamed of Italy, had no expectations or preconceptions about the place, nothing that could lead to eventual disappointment, to feeling underwhelmed. The day I arrived in Rome to live, journeying by car from the UK with my cat, was the first time I’d ever set foot in town. I’ve no ambitions about my current life, other than to live it out fully, to try to stay healthy, and maybe keep writing. I never dreamed I’d want to write a book about Gogol in Rome, about our being together, about my sitting here, with him, this sunny morning over a cappuccino.