A fifteen-minute stroll from Caffè Greco, west toward the Tiber, north in the direction of Piazza del Popolo, takes you to Via di Ripetta, which I head up, a narrow corridor running parallel to the river. I pass the Mansoleum of Augustus, the Academia Belle Arti Roma, and a few artisanal artist stores that look like they’ve been here forever, maybe even around when Gogol paced this beat. After a few minutes, the cobbled passageway of Via del Vantaggio bisects Ripetta, and I turn left along it, toward number 7, at the river end of the street. On the building’s wall, at first-floor level, is a plaque, faded over time, announcing that “the great Russian painter Alexander Ivanov, lived and worked here from 1837 to 1858.”

Ivanov, one of Gogol’s closest friends, perhaps his most intimate of intimates in Rome, spent twenty-eight-years living in the city; arriving in 1830 on a student scholarship to study renaissance painting, he never returned. His building along Via del Vantaggio is everything you’d imagine for a struggling artist: a garret-studio, on a little street, romantically rundown and worn, a quaint, quiet corner of Rome’s historic center, off the beaten tourist track. Tourists cram the city all the year round, treading very well beaten tracks; yet usually you don’t have to stray too far, wander into some unsuspecting and unspectacular corner of city, to find the coast clear. As I snap photos, I’m the sole person about.

Ivanov worked here day and night on his great religious masterpiece, “The Appearance of Christ to the People,” twenty-years in the making, much admired and encouraged by Gogol, finished only a year before Ivanov’s untimely demise with cholera in 1858. Gogol never saw it completed. In Rome, he and Ivanov became an inseparable couple, inspiring one another. In Gogol, Ivanov saw a writer-prophet, a verbal messenger from God; in Ivanov, Gogol acknowledged the conveyor of the spiritual image, an artist-prophet, the incarnation of the writer’s faith in the power of art and image. Gogol became a staunch advocate of Ivanov’s, writing letters of support for the painter, requesting funds for him to finish his great masterwork. Gogol often tagged on appeals for money for Ivanov with appeals for money for himself, maintaining that artists were better patronized than writers; scholarships and grant organizations (like the Russian Society for the Encouragement of Artists) existed for them, whereas for struggling writers there was nothing.

Gogol’s profile, “The Historical Painter Ivanov,” appearing in the notorious Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends, reads one part eulogy, another part cap in hand appeal to find alms for his artist friend, starved (sometimes literally) of resources. “He goes his own way,” writes Gogol of Ivanov. “He isn’t only not seeking a professorial post and worldly advantage, but he seeks absolutely nothing, because for a long time he has been dead to everything in the world except his work…This lesson is necessary so that others may see how it is to love art: that it is necessary, like Ivanov, to die to all enticements of life; like Ivanov, to instruct oneself and consider oneself an eternal student; like Ivanov, refuse oneself everything, even an extra dish on feast days; like Ivanov, to wear a simple pleated jacket when at the end of one’s resources and scorn vain conventions; like Ivanov, to endure all, despite one’s lofty, delicate spiritual makeup.”

Ivanov was a poor talker, only able to express himself in paint. Yet he was a good listener, and it was Gogol, despite being three-years Ivanov’s junior, who did most of the talking, who assumed the lead role. The painter was infatuated with the writer, holding the latter in enormous esteem, so much so that Ivanov even included Gogol in his epic canvas, as an old man in the extreme left of the frame, standing in the water with a walking stick, an emaciated figure, uncannily resembling what the writer might have looked like had he grown old, had he made it into his seventies, wizened and stooped, piously devout, almost bald yet recognizable from his prominent snout. (Ivanov also added a discreet image of himself, sitting on the ground in the background, in Christ’s shadow, a bearded wanderer wearing a floppy hat, his profile looking upward, as youthful as he would have been when he began his painting.)

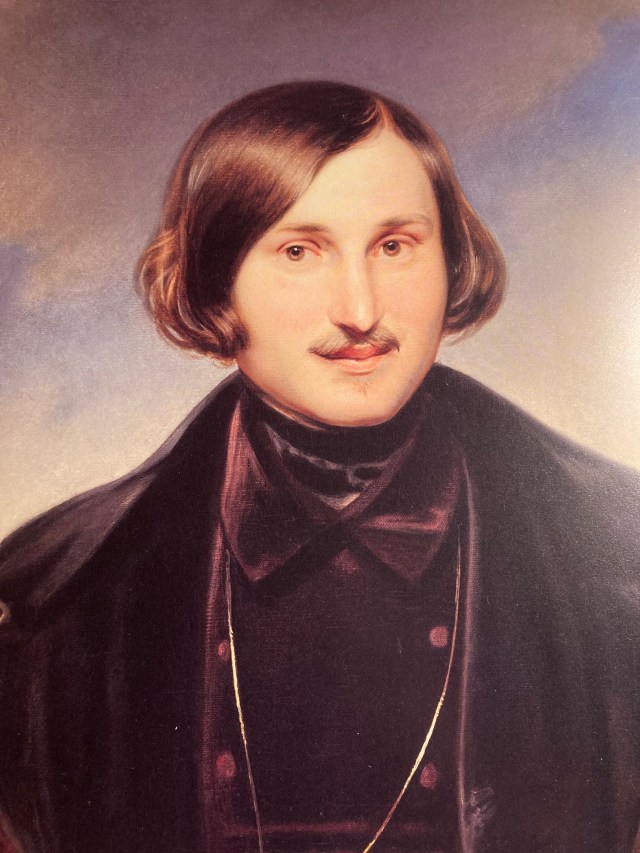

In the early 1840s, Ivanov painted two portraits of Gogol, as the writer had stipulated, “in great secrecy from everyone,” together with numerous pencil sketches, mini masterpieces in their own right. The first portrait was undertaken in September 1841; the second, more famous image of Gogol, executed in 1843, is an intimate rendering of the writer looking disheveled and dissolute, like it was painted the morning after a late night; Gogol lounges in his red dressing gown; his hair and moustache are tousled and roughed up, his eyes a little glassy, almost bloodshot. Did Gogol wander over in his dressing gown to pose in Ivanov’s studio? Or did Ivanov come to Gogol, to Via Sistina, working there from sketches of his friend, relaxed, in his domestic habitat, comporting himself without pretense, his public mask removed?

Gogol trusted Ivanov’s brush, had confidence in the discretion of his friend, portraying a purer image of how Gogol looked when he stared into his bathroom mirror each morning. When Gogol saw Ivanov’s picture, he admired and appreciated it, yet dreaded ever seeing the portrait reproduced. After Pogodin received a lithograph, the editor reprinted it without permission in his review The Muscovite for its readers to see, and Gogol’s dread of seeing himself paraded before the world, in casual garb, reached pathological proportions. He felt betrayed by a man whom he thought was a friend.

He wrote Shevyrev on December 14, 1844: “it cannot be comprehensible to someone else, why the publication of my portrait is so unpleasant to me…I am depicted there as I was in my own den. I gave this portrait to Podogin as a friend, in no way suspecting he would publish it. Judge for yourself whether it is useful to exhibit me before the world in a dressing gown, disheveled, with long rumpled hair and moustache…but it is not grievous to me myself that I was exhibited like a debauchee.” (After Gogol’s mother obtained a copy, son begged mother “to hide it in a back room, sew it up in a canvas and don’t show it to anyone to make a copy from it, not even my sisters.”)

Gogol’s attitude to portraiture was an odd mix of egoism and humility, an arrogance and a conceit of seeing himself portrayed, of wanting to see himself exhibited on canvas, immortalized and famous, yet horrified and paranoid about being displayed before the world. Portraiture, for him, became a mysterious dialectical force, both demonic and divine. He seemed unable to defy it, to avoid it, because Alexander Ivanov wasn’t the only artist he entrusted to paint him; Fyodor Möller (1812-1874), Baltic-born of German stock, was another, a painter who’d arrived in Rome in 1838 and for number of years was Gogol’s neighbor at number 43 Via Sistina.

An admirer of Ivanov, Möller soon entered Gogol’s inner fold, and he and Gogol spent a lot of time together, drinking tea and philosophizing, and Möller accompanied Gogol on his regular long jaunts around Rome and its environs. Möller recalls how they’d sometimes walk for hours on end without ever saying a word to each other; Gogol was content merely to have a companion by his side, feeling no reason to talk, humming to himself merrily.

It was out on one of their walks in 1840 when Möller made his first portrait of Gogol. This initial alla prima effort shows a radiant Gogol dressed in travel-cloak, face illuminated by rays of setting sunshine. Head lowered, his expression is sly, somewhere in between a smile and a frown. For many years, Möller kept this portrait in his own possession, eventually selling it in 1870 to Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, where it hangs today.

Möller’s second portrait, made in April 1841, mimics Ivanov’s, and captures the writer at home, wearing another dressing down, a fawn stripped one, with his pajama top open, revealing part of Gogol’s bare chest. This time, though, Gogol’s hair is neatly coiffed, his little moustache coquettishly manicured. His face is plumper than Ivanov’s image, pink round cheeks giving him a healthier looking glow, highlighting how, despite literary fame and prominence, Gogol was still rather baby-faced.

Möller’s best-known portrait was his third, painted at the end of 1841, commissioned by Gogol’s mother, Maria Ivanova Gogol-Yanovskaya. A more classical, formally-posed Gogol looks neat and dandy, smartly dressed in elegant button-downed frock-coat and silk scarf, stylishly knotted at the neck, with a classy looking gold chain dangling around his front. This is the writer with a glint in his eyes, and just a hint of a grin, ready to dine with mother in some fancy restaurant.

Möller’s portrait was highly acclaimed, reckoned to capture Gogol’s true appearance, something seemingly accessible only to an intimate. In 1845, Gogol said “Möller’s portrait was the only one to give a good likeness.” Until 1919, the portrait remained in the Gogol household, whereupon it was transferred to the Yaroshenko Museum in Poltava, Ukraine. During World War II, though, it disappeared; thought destroyed, it never showed up again. This image of Gogol that Möller created in Rome, today likewise displayed in Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, is thus a copy.

***

Interestingly, and surely not uncoincidentally, while Ivanov and Möller were painting portraits of Gogol, Gogol himself was immersed in creating (and re-creating) his own Portrait, one of his best-known short stories. He’d originally published it almost a decade earlier, in Arabesques (1835), “a mishmash” collection (according to Gogol) of fiction and non-fiction, of essays on art and architecture, on the Middle Ages, on Pushkin, alongside two other brilliant stories, The Nevsky Prospect and Diary of a Madman. On March 17, 1842, Gogol wrote Peter Pletnev, editor of The Contemporary (Pushkin’s journal): “I’m sending you my story, ‘The Portrait.’ It was printed in Arabesques, but don’t let that worry you. Read it through and you will see that only the canvas of the former story remained, and everything is embroidered on it anew. In Rome, I reworked it completely.”

The Portrait (Take-1) had been written before he’d met either Ivanov or Möller; it’s fascinating to speculate whether in Ivanov Gogol had found a real life reincarnation of the fictional artist who cameos near the end of the story, and who embodies Gogol’s own artistic ideals, or if Ivanov had himself became a creation of Gogol, mimicking and fulfilling this ideal, the spiritually pure artist whose canvas left viewers gasping in awe.

Vissarion Berlinsky, the well-known liberal critic, thought the supernatural in Take-1 too clumsy, not leavened by the story’s brilliant realism, a feature, Berlinsky said, that made Gogol’s most unbelievable and incredible moments believable and credible. Gogol, as ever, took only part of Berlinsky’s critique to heart; in Take-2 he’d never abandon his torquing of reality, never expunge the surrealist flourishes that made his ordinary so extraordinary, his satire so biting, his creations so idiosyncratic and original. He was much too subtle an artist to capitulate to either the dullest period-piece realism or the most contrived and fantastical surrealism. Gogol would forever work against predictability, often turning his own inventiveness against itself, just when we’d least expect it, having us, his readers, twist and turn as his characters twist and turn, as he himself twists and turns, gyrating to some weird cosmic force.

Indeed, Gogol’s The Portrait once had a powerful gyrating effect on me, too, a ghostly presence when I think about it now, remembering the mornings, years gone by, when I used to walk my daughter to school. Along a narrow old lane, near the town center, by the cathedral, we’d pass a little pub called “The Prince Albert.” On a pole sticking out above the pub’s entrance hung a portrait of the said Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, painted by royal artist John Partridge in 1840. On windy days, the prince oscillated in the breeze. Every morning I’d grin, laugh to myself, sometimes laugh out loud. It got a bit boring for my daughter, for she knew what I was laughing at. After all, I’d tell her every day, “you know, that Prince Albert up there, he’s a dead ringer for Gogol.” She knew, too, that I meant Nikolai Gogol, a longtime favorite of mine. The thin prominent nose, the vivid eyes, the little well-groomed moustache, the general affected air, camp despite the military regalia—all that was Gogol to a T!

I’d actually seen for myself Möller’s best-known image of Gogol in 2016, not knowing then it was a copy, at London’s National Portrait Gallery, displayed at an exhibition called “Russia and the Arts.” This was Gogol at his most Prince Albertian—or was it Prince Albert at his most Gogolian? The notion that Gogol had a doppelgänger, that Prince Albert was secretly Gogol, or that Gogol was secretly Prince Albert, sneaking out of Russia, condemned for his mockery of provincial officialdom in the rollicking drama Government Inspector, eloping clandestinely into British royalty, struck me as itself quintessentially Gogolian.

Roaming Europe under an assumed identity was as bizarre and surreal as only Gogol could render believable. “There was always something bat-like or shadow-like in his flittings from place to place,” Nabokov says. “It was the shadow of Gogol that lived his real life.” His antics when traveling were legendary, often assuming fictitious names like Gogel and Gonel, hating having to show his passport. Play-acting was a standard repertoire, feigning losing his documents, rummaging through his suitcase, causing a scene and getting angry, swearing, manically throwing out his clothes until customs officials finally gave up and let him pass. (When younger, Gogol sometimes signed himself off “0000,” four-zeros stemming from the four “o”s in “Nikolai Gogol-Yanovsky,” his full name. “The selection of a void,” suggests Nabokov, “and its multiplication for concealing his identity, is very significant on Gogol’s part.”)

Maybe I’d read too much Gogol to think up such a pairing, even though Gogol and the German-born Prince Albert (1819-1861) were actual contemporaries, both dying relatively young, each aged forty-two. Yet it was seeing Prince Albert with his bird-like nose, and glimpsing Gogol’s image in London’s Portrait Gallery—with his own famous beak—that had me recall The Portrait; and I’m having a déjà vu sensation here in Rome thinking about it, standing outside Ivanov’s old building, remembering how Prince Albert’s eyes used to stare out like the eyes that leapt out on Gogol’s poor young artist Chartkov, The Portrait’s (Take-2) protagonist.

Gogol has Chartkov rifling through dusty worn paintings one day at a cheap Petersburg art shop. There he stumbles across a portrait of an old man, with a gaunt, high-cheek-boned face and bronze skin. Most extraordinary of all were the eyes. After much deliberation, and bargaining with its owner, the young artist parts with his last few kopecks and staggers back with the canvas to his draughty studio in the grungiest part of town. Once there, says Gogol, “the two terrible eyes fixed directly on him, as if preparing to devour him.”

At nightfall, trying to doze on the sofa, Chartkov can’t bear the thought of those eyes staring at him like some terrible phantom. He tosses a bedsheet over the portrait. But the moonlight only intensifies its whiteness and ghostly presence, “endowing it with a strange aliveness.” As Chartkov falls asleep, Gogol’s quill springs into action. The white sheet is no longer there; the old man has stirred. Suddenly, leaning on the frame with both hands, he thrusts both legs out to free himself of his confinement. Chartkov attempts to scream yet has no voice. The old man steps down, takes out a sack containing packets of fabulous golden rubles. One pack drops to the floor; Chartkov runs over, clutches it, tries to prize it open but can’t. He cries out—and wakes up.

Chartkov’s heart pounded “as if the last breath was about to fly out of it.” Could it have been a dream?” he wonders. “My God, if I had at least part of that money,” he sighs. Awake, he removes the sheet and sees the old man still inside his frame, his “living, human eyes peering straight into him.” Sweat dripped from Chartkov’s brow, cold sweat. He wanted to back away from those eyes, “but felt as if his feet were rooted to the ground. And he saw—this was no longer a dream—the old man’s features move, his lips begin to stretch toward him, as if wishing to suck him out…With a scream of despair, Chartkov jumps back—and woke up.” “Could this, too,” Gogol asks, “have been a dream?”

Now, his heart is pounding so intensely, it’s on the point of bursting. Terrified, Chartkov dared look again at the portrait; the sheet was still over it. So perhaps it had been a dream after all? And yet, as he continued to look, the sheet began to move once again, hands fumbling under it, inside it, desperately trying to throw off the cover, doing so with menace and impatience. “Lord God, what is this!” Chartkov cries, not believing his eyes, and, crossing himself desperately, suddenly wakes up.

By morning, the room is bleak and gloomy; “an unpleasant dampness drizzled through the air.” It seemed “that amidst the dreams there had been some terrible fragment of reality.” Then a knock at the door heralds the arrival of the landlord and a police inspector, “whose appearance,” Gogol says, “as everyone knows, is more unpleasant for little people.” The landlord, a retired civil servant, “an efficient man, a fop, and a fool, who had merged all these sharp peculiarities in himself into some indefinite dullness,” wants the unpaid rent. Chartkov, with little else, offers him his paintings. But the landlord scoffs, uninterestedly. Meanwhile, the inspector examines the portrait of the old man. As he clumsily picks it up, its frame splits apart. One side falls to the ground along with a packet, wrapped in blue paper, with the inscription “1,000 Gold Rubles.” Chartkov, like a madman, rushes over, seizes the heavy packet.

His woes are over, or so it would seem. Now he has a fortune—as foreseen in his dream. He pays off the landlord, installs himself in a swanky bourgie apartment along the Nevsky Prospect, gets his hair curled, begins sporting fashionable tailored suits, dines at fancy French restaurants, and struts along the sidewalk admiring himself like the most elegant of dandies. Strangely, too, Chartkov’s reputation as a great artist soars. He gets a Petersburg newspaper to publish an article he’d written himself, about his own extraordinary talents, a brilliance worthy of any Titian or Van Dyck. Petersburg’s elite become mesmerized by a new genius in town, and flood him with commissions.

At first, his portraits glow with subtle brush strokes and masterful shading. But sitters want less, are thrilled by cliched images, by empty smiles and upper-crust stiffness. The shallower the portrait, the better—and the more he’s in demand. He’s rewarded with everything: money, compliments, handshakes and kisses, invitations to dinners, to glamorous soirées. Soon, says Gogol, “it was quite impossible to recognize in him that modest artist who had once worked inconspicuously in his hovel.”

The years pass, and slowly but surely the luster of riches and finery wears thin. Chartkov tires of churning out hundreds of the same portraits, of the same faces, whose poses and attitudes he knows now by rote. “His brush was becoming cold and dull, and he imperceptibly locked himself into monotonous, predetermined, long worn-out forms.” What’s more, “he was already beginning to reach the age of maturity in mind and years and already began to gain weight and expand visibly in girth.”

By midlife, Chartkov had become blasé, banal in his state of mind, banal in his state of brush. “Even the most ordinary merits,” Gogol writes, “were no longer to be seen in his productions, and yet they still went on being famous, though true connoisseurs and artists merely shrugged as they looked at his latest works.” He’d “touched upon the age when everything that breathes of impulse shrinks in a man,” says Gogol,

when a powerful bow has a fainter effect on his soul and no longer twines piercing music around the heart, when the touch of beauty no longer transforms virginal powers into fire and flame, but all the burnt-out feelings become more accessible to the sound of gold, listen more attentively to its alluring music, and little by little allow it imperceptibly to lull them completely. Fame cannot give pleasure to one who did not merit it but stole it. And therefore all his feelings and longings turned toward gold. Gold became his passion, his ideal, fear, delight, purpose.”

Still, one event shook Chartkov deeply, and “awakened all his living constitution.” When the Academy of Art invites him to judge a new work by a young Russian artist, an Ivanov figure, already being hailed a great genius, he’s skeptical. After seeing the canvas in the gallery, surrounded by hordes of visitors, he’s stunned: the purest, most immaculate conception hangs on the wall, a painting so modest, so divine that tears flow down the cheeks of onlookers. Chartkov is blown away, stands motionless, “open-mouthed before the picture.”

His whole being, says Gogol, “is reawakened in one instant, as if youth returned to him, as if the extinguished sparks of talent blazed up again.” The blindfold suddenly falls from his eyes, and he realizes he hadn’t heeded his wily old professor’s advice from long ago. He’d ruined his best years, neglected the long, arduous lesson of gradual learning. Instead, he’d become that dreaded species: a fashionable painter. (One wonders if John Partridge, Prince’s Albert’s depicter, ever felt the same way, ever regretted his life as a court artist, whipping off those fawning portraits of royalty and society people?)

Chartkov could no longer bear those lifeless pictures, the portraits of buttoned-up hussars and state councilors, of eternally tidied ladies; he orders them out of his studio. Then he remembers the strange portrait he’d purchased, which had kindled all his vainest impulses, and heralded his demise. A rage bursts into his soul. Bile rises up in him whenever he sees a work marked with the stamp of greatness. He begins to buy up great masterpieces, hauling them back to his room, where he tears them apart, shreds them, cuts them to pieces in a savage orgy of destruction that portends Chartkov’s auto-destruction, bizarrely mimicking Gogol’s own auto-destruction. A cruel fever, compounded by galloping consumption, eventually sees our artist off. “His corpse was frightful,” Gogol notes. “Nothing could be found of his enormous wealth; but seeing the slashed remains of lofty works of art whose worth went beyond millions, its terrible use became clear.”

***

In his epilogue to The Portrait (Take-2), Gogol tells us that the old man with those terrible eyes had been a dreadful moneylender, a loan shark who extorted Petersburg’s poor, sometimes extorting even Petersburg’s rich. Calamity befell upon everybody who took money from him. He possessed some dark curse, damning him and anyone he touched. Even the artist who painted his portrait was struck down by demons, managing to cast them off only by becoming a repentant hermit monk. The painting similarly imparted devilish forces, and tragedy afflicted everyone who owned it, who felt its burning eyes. At the story’s close, as the painting is about to be auctioned off, the painter’s son suddenly appears, demanding the thing be burned, destroyed at all costs—or else.

Gogol worked over The Portrait many times, adding and amending, chopping and changing, deftly touching it up in Rome, reshaping it into one of his finest stories, with some of his best writing; still only in his early thirties, he seemed to have reached the peak of his literary powers, a maestro of the shorter vein. His evocations of Chartkov’s dream phases are so vivid that they capture in prose exactly the blurring of Rapid Eye Movement sleep from wide-awake experience, the imagining of real life, sounding like we’re reading Chartkov in real time, only to find that Gogol wakes us up to the fact it had been a dream all along.

Gogol, meantime, tells us plenty about the role of the artist in our society, about the dichotomy between artistic integrity and everyday materialism, between the art of pure creation and the act of earning a living. It equally says a lot about Gogol’s own plight in the world, too, about his allegiances with “little people,” about how art for him ought to make the highest service toward the moral good. He knew that in a society dictated by money values and governed by shallow, buttoned-up people, genuine artistic passion will always be up against it. Artists like the young Chartkov (and Ivanov) are isolated and destitute, dedicated to their creation, yet fair game to be bought off, commissioned as hired hands, seduced by all the trappings of high society. (Ivanov never relented, of course, was never bought off, never sold out his great romantic dream for art, and that’s likely why Gogol admired him so.)

In 1844, two-years on from Gogol’s Portrait, we might recall Karl Marx in his Parisian garret, a young man not much older than a struggling Chartkov, pillorying, with Gogolian irony, “The Power of Money in Bourgeois Society.” Money, says Marx, “is the universal whore, the universal pimp of men and peoples,” the “inversion of all human and natural qualities.” Marx calls money a “divine power,” “as the estranged and alienating species-essence of man which alienates itself by selling itself.” Money turns one thing into another, inverts everything it touches, converts people and objects into their opposites, into “contradictory qualities” antagonistic to their own qualities.

As such, money “transforms loyalty into treason, love into hate, hate into love, virtue into vice, vice into virtue, servant into master, master into servant, nonsense into reason and reason into nonsense.” And a money tag transforms bad art into a good art, the rich artist into a veritable genius. With its implicit disdain for how money corrupts, The Portrait exhibits more than a hint of young Marx’s romanticism, cautioning us about wish-fulfilment, that we better watch out what we dream for in youth because we might get it later in life. Dreams, needless to say, are a motive force of our lives; yet in a society that conjures up canned dreams, they’re also dark places where danger lies to ambush, where manufactured dreams are available to anyone—at a price. Which reinforces something I suspect I knew all along laughing each morning at Prince Albert long ago: that Gogol’s Portrait is really a picture of ourselves.

Pingback: PICTURING GOGOL | andy merrifield