Gogol was passionate about food, reached obsessive proportions with it—in the portion sizes he consumed, in the elaborate descriptions around the dinner table in his stories. Zolotarev speaks of Gogol’s “stupendous appetite.” He and Gogol dined together often in Rome, tucking away at big dinners. Yet if another of Gogol’s friends happened to enter the restaurant, Gogol would stick around, eat with them, ordering the same meal again. Friends marveled at how such a modest body could put away so much food.

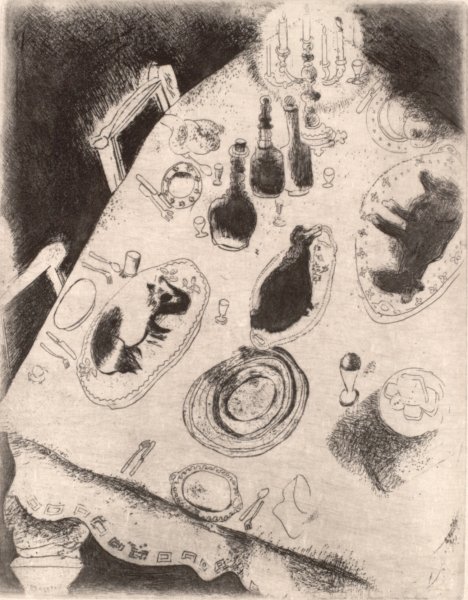

When Pogodin visited Gogol in March 1839, he and other friends spied on the writer at his regular haunt, the Falcone, near the Pantheon; Gogol apparently ate there most nights. Hiding in a backroom, they heard him order “macaroni, ravioli, and broccoli,” Pogodin recalls. “The waiters went running all over the place, fetching this and that. His face all aglow, Gogol took the dished and ordered still more. Now before him stood green salads piled high, flagons filled with pale liquids. There was agrodolce, spinach and ricotta ravioli, melanzane impanate, pesto chicken wings, zuppe, frittura mista. An enormous plate of spaghetti was brought before him, and thick steam rose from it when they removed the lid. Gogol tossed a lump of butter onto the pasta, liberally powdered it with parmesan, assumed a pose of a priest about to offer sacrifice, seized a knife and dug in. That’s when we flung open the door and rushed in, laughing, ‘Ah-ha, so your appetite’s gone, and your stomach’s all upset?’”

It’s clear that Gogol loved food, good food, hearty food, nothing fancy, homely cooking. He was passionate about eating and cooking, about dining with friends, about entertaining friends around food, about preparing meals for them—“I’m mad about good food,” he had his rogue Khlestakov say in The Government Inspector, “what else is life for except to pluck the blossoms of pleasure?” “More than anything,” Khlestakov’s manservant Osip says of his master, “he likes warm hospitality and good grub.” Gogol’s characters speak for their author, whose mind seems as frequently on food as that other rogue, Chichikov, who muses about his next meal as much as amassing dead souls. Food crops up so often in Gogol’s writings that it almost becomes a character in itself.

Part of Chichikov’s delight in visiting provincial estates is how he might satisfy his belly, how he might feed his face. In fact, Gogol toys with his readers with Chichikov, writing “the author admits that he is quite envious of the appetite and the stomach of this type of human.” It’s a far cry from prissy urban aristocrats who daintily pick at their food with old silver forks, popping a pill before eating; Gogol’s heroes are hearty eaters like Chichikov, ordinary and middling rural and provincial folk. “No, gentry have never aroused his envy,” says Gogol’s narrator. “But he is envious of certain persons of intermediate status who at one way station will order ham, at the next suckling pig, at a third a slice of sturgeon or salami with garlic, after which, as though they hadn’t eaten a thing, they’ll sit down at any time and have a fish soup with eels and roe and everything with it, which hisses and gurgles in their mouths, followed by all sorts of pies—well, these people have an enviable, heaven-sent gift indeed!”

“Got any suckling pig”” Chichikov asks a peasant woman at an inn. “’Right’. ‘With horse radish and sour cream?’ “With horse radish and sour cream’. ‘Bring it here then!’” When Chichikov dines at Sobakevich’s estate, he knew he’d met his culinary match, his gastronomic equal. “This one’s no novice when it comes to eating,” Chichikov thinks, “he helped himself to about half of a saddle of mutton and proceeded to gnaw it clean and suck dry every last bit of bone…The saddle of mutton was followed by round cheese tarts, each larger than a good-sized plate; then a turkey, about the size of a calf, stuffed with all sorts of things—eggs, rice, liver, and God knows what; all of which formed a heavy lump in the eaters’ stomachs. When they rose from the table, Chichikov felt himself about forty pounds heavier.”

Gogol hadn’t finished with food by the time he worked on Part 2 of Dead Souls, before he threw much of it in the fire. What survives as drafts feature food, and Chichikov is still munching his way across provincial Russia, still dining with provincial gentry, freeloading as ever. On one occasion he’s the guest of an obese foodie, Piotr Petukh, who eats himself and invitees out of house and home. Good job he lives in the cheaper countryside, Chichikov muses to himself; in Petersburg or Moscow, his generous hospitality would fast render him a pauper.

“The servants kept coming and going with remarkable speed,” writes Gogol, “constantly bringing something in a covered dish from which the sound of sizzling butter could be heard…Chichikov ate virtually twelve pieces of something and was thinking, ‘Well now our host isn’t going to add anymore’. Quite wrong: without a word, Petukh put on his plate a rack of veal, with kidneys, spit-roasted, and what a calf, too. ‘I reared it on milk for two-years’, said the host. ‘I looked after it as if it were my own son’. ‘I can’t’, said Chichikov. ‘Try it first and then say I can’t’. It won’t go down. I’ve no room’.” Still, Chichikov does try it and, rather inevitably, found room, “when it seemed that no more could be crammed in.”

Our hero went to bed with his stomach “taut as a drum.” And even then, lying there, he could hear his host Petukh talking in the kitchen with his chef about next day’s lunch, making plans for another feast, giving precise instructions about its preparation. “’Make the fish pie with four corners’, Petukh said, sucking his teeth and taking a gulp of air. ‘Put the sturgeon’s cheeks and dried spine in one corner, put the boiled buckwheat in the second corner, with mushrooms and onion, and some sweet milk and the brains and a bit of this and that, you know what…And make sure it is browned on one side, you know, and a bit less done on the other side. And bake the underneath so that everything is absorbed, so that all the taste comes through, so that it all, you know, not crumbles but melts in your mouth, like snow, so that you don’t notice!’ As he said this, Petukh smacked his lips and chomped.”

“And to garnish the sturgeon,” he adds, “cut the beets in the star shapes with smelts and milk-cap mushrooms, and add some, you know, turnip and carrot and broad beans and a few other things, so we have a garnish, as big a garnish as possible. And put a bit of ice into the pig’s belly to make it swell up nicely.” “And Petukh ordered many more dishes. All that Chichikov heard was ‘and fry it and roast it and let it stew nicely’. When Chichikov got to sleep, turkey was being discussed.”

This is hilarious, deadpan humor, written clinically and matter-of-factly; but it’s Gogol at his comic best, the master of satire, its darkest. (I’ve always thought it a pity that André Breton never included Gogol in his masterly collection of surrealist black humor, Anthologie de l’humour noir.) Like Petukh, Gogol is obsessed by food, but his parodies of his characters’ obsessions seem equally a parody of himself, of his own obsessions, because he’s able to see through them, recognize them, pull tongues at himself. One of his weirdest tongue pullers is Diary of a Madman, where even the dogs have their minds’ fixated on food. About having nothing to eat, one says: “I must confess that would be no life for me. If I didn’t have woodcock done in sauce or roast chicken wings, I don’t know what would become of me…Sauce goes very well with carrots or turnips, or artichokes…” Remember, Gogol’s eponymous madman hears dogs talking to each other in human language.

But Gogol’s catalogue of gastronomic delights also exhibits real insight into food, into its preparation and meaning in life. He fretted about noses, especially his own, another obsession; and yet without a sense of smell, there’d be no sense of taste, nothing to salivate about. And Gogol lets us sniff the culinary gorgings he presents for us. For good reason did Nabokov say that “the belly is the belle of his stories, the nose their beau.” Perhaps not unsurprisingly as well, Gogol not only loved to eat; he took enormous satisfaction cooking for others, for his friends, finding in Italy a culture with a deep sensitivity and appreciation of food, of its conviviality, one of the joys of collective life, pure and simple, like eating cabbage soup around the rural Russian kitchen table.

In Rome, meanwhile, he’d mastered the art of how to prepare baked macaroni, something of a house specialty when friends came over to via Sistina. He was fanatical about his macaroni, ritualistically make masses of it, piping hot, sizzling from the oven, drooling with copious dollops of butter and grated parmigiano. He’d never skimp on making it as creamy and delicious as possible, with calories galore. Gogol’s spirits would rise whenever he had the chance to serve up his macaroni to friends. “Opening the lid, with an especially bright smile for everyone at the table,” Pogodin remembers, “he’d exclaim: ‘Now fight over this, people!’”

The only problem was that while Gogol loved food, food didn’t always love him. He suffered over it, suffered some mix of constipation and diarrhea, compounded by (and related to) his arch-complaint: hemorrhoids. Was this prompted by overeating? Too much of the wrong foods? Too much fat? Too much butter and cheese? Gogol would pile on the butter, devour parmesan, indulge in the most indulging foods—and afterward complain about his stomach. Go figure…

Was it a genuine nervous stomach? Or just Gogol at his most hypochondriacal, always super-sensitive about his own health? “I’m afraid of the hypochondria,” he wrote Prokopovich from Geneva (September 19, 1837), “which is changing me and is right on my heels.” “My stomach is nasty,” he says, “to an impossible degree; and although I eat very moderately now, it absolutely refuses to digest. After my departure from Rome, my hemorrhoidal constipation began again, and would you believe it, if I have no bowel movement during the whole day I feel as if my brain had some kind of cap pulled over it, which befogs my thoughts and prevents me from thinking. The waters didn’t help me at all, and now I see that they are terrible rubbish, I just feel worse, my pockets are light and my stomach heavy.”

You have to know who your real friends are to write them letters like this.

Elsewhere, to Pogodin from Naples (August 14, 1838), he says: “my hemorrhoidal disease has turned all its force on my stomach. It’s an unbearable disease. It’s drying me up. It tells me about itself every minute and hinders my work.” Gogol seemed trapped in a vicious cycle of real ailment and imagined ailment; the latter hypochondria triggered the former, and the two probably fueled each other. As Gogol wrote a few years earlier (1836), from Paris: “my doctor found symptoms of hypochondria in me, resulting from the hemorrhoids; and he advised me to amuse myself…there are a multitude of places for walks…enough for a whole day’s exercise—which is essential for me now.” Sometimes, says Gogol, “I feel awful crap in my stomach, as if someone had driven a whole herd of horned cattle in there.”

***

In an insightful essay, “The Hunger Artist: Feasting and Fasting with Gogol,” published in The Global Gourmet (June 28, 2008), the food scholar Darra Goldstein assesses Gogol’s digestive torments. Her theory is that Gogol suffered from what today has been diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), “which presents itself in a number of different ways,” Goldstein says. “Some people endure constipation,” she says, “others diarrhea; some, like Gogol, suffer from both. In all cases, IBS causes great discomfort and distress and can be disabling.” “Emotional conflict or stress is often believed to trigger the condition,”Goldstein says, “though most likely IBS results from both stress and improper diet.”

Gogol’s IBS might have been triggered by the fattiness of his diet, by all that cheese and butter, by all the rich food he seemed drawn to; his nervous reactions and hypochondria sought only to make compound matters. He seems to realize this himself, writing to Pogodin from Rome (October 17, 1840): when his stomach plays up, he says, “the nervous disorder and irritation increased terribly; a heaviness and pressure in the chest which I had never before experienced grew strong. Fortunately,” Gogol goes on, “the doctors found that I haven’t consumption, that this was an extreme irritation of the nerves and a stomach disorder which stopped digestion. This didn’t make me feel any better…A painful anguish which has no description was combined with this. I was brought to a state that I absolutely didn’t know where to turn, where to find support. I couldn’t stay calm for two minutes in bed or in a chair or on my feet. Oh, it was terrible.”

“There’s still no cure for IBS,” notes Goldstein, “and apart from recommended moderation in diet—something Gogol seems to have been temperamentally incapable of—there is no real treatment.” Moderation around food was especially hard for Gogol, thinks Goldstein, doubtless correctly, as “his illness, his gut feelings, fed his art. His source of torment—his appetite—became his inspiration, his muse, transforming into literature the hunger that affected his whole being. His gourmandizing bespoke something beyond a mere physical urge; his hunger was existential, not easily satisfied.” All of which strikes as a more wholesome and accurate assessment of Gogol’s gastric literature.

I say this because it’s suggested that Gogol’s obsessions with food are really transferences of his repressed obsessions with sex. Gogol was a strange man, for the most part a-sexual though with evident homosexual tendencies; yet there’s nothing repressed about his obsessions with food. It is what it is. Nabokov made the same point of Gogol’s nose fetish, locating it as much in Russian folkloric history and culture as in psychology and psychoanalysis.

To that degree, Gogol’s foodie manias reflect the experience of growing up, of a rural upbringing—quite the reverse of anything repressed: these Russian festivals and village fairs from his childhood, source material for his early Ukrainian stories, abound with food and drink, and toast life’s pleasures. If anything, they were more collective “blow-outs,” what François Rabelais in sixteenth-century France called “ripailles.” This medieval tradition had its own vitality in the Russian rural provinces, defined seasonality and collective memory, the good fortune of being alive, that you can enjoy it, if only for a day. Who knows or cares about tomorrow?

What took place weren’t simply meals shared by the townsfolk but celebrations of conviviality and appetite, celebrations of terrestrial life itself. Affirmed was abundance and generosity, gorging and over-indulgence in the absence of moderation. Three-cheers to excess! It’s surely not too far removed from how Gogol implicitly used his prodigious food and feast scenes. Food, for him, was more anthropology than sexology, something more personally cultural and historical. Food gave Gogol, the writer, insights into the Russian psyche, into everyday cultural life, especially everyday provincial life. (Food never figures in the same way for an urban Petersburg gentry; there it really does become something repressed.)

A meal, in this provincial context, could be something soothing, an act of diplomacy, a moment when you sit around the dinner table, perhaps with an enemy. When the two Ivans—once dear friends, neighbors so close and intimate they were like brothers—had their great tiff, falling out over a trifle, with one Ivan calling the other Ivan a “goose”—the town tried to reconcile the quarrel by organizing a sumptuous dinner. Food was taken as something placatory, a ritual that could bring people together.

“I will not describe the courses,” Gogol’s narrator says, before going on to describe the courses: “I will make no mention of the curd dumplings with cream sauce, nor of the dish of pig’s fry that was served with the soup, nor the turkey with plums and raisins, nor the dish which greatly resembled in appearance a boot soaked in kvass, nor of the sauce, which is the swan’s song of the old-fashioned cook, nor the dish which was brought in all enveloped in the flames of spirit.” Still, even this great feast couldn’t bring the former friends together, such was their animosity toward one another; even food couldn’t make this little world less gloomy, says Gogol, at the end of his story.

Gogol was a great populist when it came to food, a democrat who wanted to share his meals with others, with friends, who enjoyed cooking for others, and dining out amid people, oftentimes with “the people.” (He rarely dined alone.) This was particularly so in Rome, where he was fond of the more plebian, down-to-earth taverns, rubbing shoulders with the common folk. The Russian historian and memoirist, Pavel Annenkov, who wrote an early Pushkin biography, remembers visiting Gogol in Rome in the 1840s. “My friend Gogol took me to the famous Lepre tavern, where at mealtimes, at long tables, crossing the filthy floor, a diverse crowd gathers: painters, foreigners, abbots, citizens, farmers, and princes join in a general conversation, devouring the very dishes that, in truth, thanks to the chef’s long experience, are impeccably cooked.” (Annenkov lived with Gogol for two months in Rome and in his reminiscences said that he copied large sections of Dead Souls, listening and trying to follow Gogol’s rapid-fire dictation.)

Interestingly, at the same time as Annenkov was visiting and dining with Gogol in Rome, he was also engaging in a lively dialogue with a certain Karl Marx in Paris. The twentysomething Marx and Annenkov (1813-1887) were practically contemporaries, and seemed to find agreement in their criticism of anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Annenkov met both Marx and Engels in Brussels in the spring of 1846, witnessing a fierce public debate between Marx and Weitling. Later, in December 28, 1846, from Paris, Marx wrote Annenkov a very long letter in what Marx admitted was his “bad French,” addressing the defects of Proudhon’s Philosophie de la misère. Annenkov told Marx on January 6, 1847, that “your opinion of Proudhon’s book produced a truly invigorating effect on me by its preciseness, its clarity, and above all its tendency to keep within the bounds of reality.”

When Annenkov published his reminiscences of an Extraordinary Decade, 1838-1848, he was perhaps the only man alive to have rubbed shoulders with both Gogol and Marx. Turgenev called Annenkov “a master at crystallizing the specific character of a period.” That extraordinary decade, of course, was to produce not only dramatic political upheavals throughout Europe, but also, and maybe not uncoincidentally, texts like The Communist Manifesto (1848), as well as some of Gogol’s best short stores, especially “The Overcoat” (1842).

No matter where he went, whether eating high or low, Gogol was forever fastidious about his food. Annenkov remembers he often asked Orillia, Lepre’s legendary old waiter, rumored to have been in Moscow with Napoleon’s army, to change any dish he didn’t find to his liking. Fyodor lorden (always lower case “l”), a Russian engraver friend of Gogol and sometime via Sistina neighbor, recalled that at the Lepre (“hare” in Italian) “you could meet people from all parts of the world; at every other table another language was being spoken, of which Russian reigned over the rest, outmatching them in the noise of loud arguments.” By all accounts, the Lepre was the cheapest and most democratic of Rome’s trattorias, with one of the best cuisines. (In the 1850s, a decade on from Gogol, Herman Melville, a regular, marveled at the quality and price of a full meal: nineteen-cents.)

Nothing remains of the Lepre today. There are no images (apart from a painting of a mother with her two daughters, lunching heartily at an establishment thought to be the Lepre), and no physical remnants left inside the courtyard of the Palazzo Maruscelli Lepri, where the Lepre was located—via Condotti, 9-10, exactly opposite Caffè Greco. The palazzo itself was constructed in 1660 for the Maruscelli family, who sold it later in the eighteenth-century to the Lepri family, wealthy Lombard merchants who’d settled in Rome a century prior. But the Lepris fell on hard times during the nineteenth-century, and the marquis, on the verge of financial ruin, began renting out rooms in the palazzo’s courtyard. The family’s cook had always dreamed of opening his own restaurant and offered to feed the marquis and his entire family for five sous each, provided they let him open a small trattoria in the kitchen on the ground floor of the building. The marquis agreed.

The trattoria, inaugurated as “Trattoria della Barcaccia”—on account of the “Fountain of the Barcaccia” [Longboat] facing the Spanish Steps—later changing its name to “Trattoria della Lepre,” quickly became one of the most famous eating houses frequented by tourists and émigrés. The Lepre was famous for another reason, because it’s reputed to have served supplì, the famous Roman street food, its first recorded mention in Roman history, in 1874, when the deep-fried, golden and crispy risotto rice croquettes, filled with mozzarella, minced beef and tomato sauce, were listed on the Lepre’s antipasto menu. It’s the sort of snack Gogol would have doubtless wolfed down.

Gogol lapped up the tavern’s raucous atmosphere, its culture and honest cuisine. Before long it became a surrogate members club for Russian expats, especially Russian painters, where they could listen to articles from the Russian press read aloud. It was at the Lepre where Gogol first heard and appreciated the Romanesco sonnets of Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, voiced by the renegade poet himself, in Roman dialect, in the speech of Trasteverines—i trasteverini. Belli satirized the clerics and the popular classes of his day, castigating the hypocrisy of the former and the passivity of the latter. His verse, unpublished in his lifetime, was rooted and voiced in the language of his chosen constituency: the unflinching everyday reality of Rome’s underclass.

(Anthony Burgess, a fan, translated some of Belli’s sonnets, putting them into Mancunian slang in his 1977 novel, Abba Abba, emphasizing cultural translatability if not literary accuracy. Burgess said “Belli was the great master of the dialect and scholarly recorder of Rome’s filth and blasphemy.” Abba Abba, a fictional account of Belli meeting the English poet John Keats, another Rome denizen, presented seventy-one of Belli’s Roman sonnets in its second part, translated by J.J. Wilson, a pseudonym for Burgess himself—his full name is actually John Anthony Burgess Wilson. Burgess wanted to call his novel Belli’s Blasphemous Bible, but publishers Faber & Faber, fearing libel, balked, talking Burgess out of it.)

Gogol was privileged to hear Belli reading at the Lepre and expressed his enthusiasm in his letters. He wrote Maria Balabina (end of April 1838): “Not one event takes place here without some witticism or epigram being made up by the people. But you probably haven’t happened to read the sonnets of the present-day Roman poet Belli, which, however, one must hear when he reads himself. In them, in these sonnets, there is so much salt, so much totally unexpected wit, and the life of present-day Trasteverines is so faithfully reflected in them that you will laugh, and the heavy cloud which so often floats down on your head will float away together with your tiresome and annoying headache.” High praise indeed!

Gogol sang Belli’s praises in 1839, on a Roman steamboat bound for Marseille, when he encountered the French literary critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve. Gogol seemed to have made a big impression on Sainte-Beuve, who felt compelled to write about his maritime brush with the Russian writer, about his conversations, reviewing at the same time the recent French publication of Gogol’s Cossack novel, Taras Bulba: “Monsieur Gogol told me of having found a true poet,” Sainte-Beuve recalled, “a popular poet, called Belli, who writes in the language of trasteverines, but makes sonnets follow and form poems. Gogol spoke to me in depth and in a manner to convince of the original and superior talent of this Belli, who rests so perfectly unknown to all travelers.”

Sainte-Beuve commented “it is doubtful that any Frenchman had ever read one of Monsieur Gogol’s original productions; I, in this case, was like everyone else. I can, however, claim the advantage of having met the author in person, and I had, after his precise and strong conversation, rich in observations of morals, grasped a foretaste of what must have been original in the works themselves. And Monsieur Gogol, in effect, seems to attach himself before all else to the fidelity of morals in the reproduction of the true and of the natural, whether in the present time or in the historical past; the popular genius preoccupies him, and no matter where its look reveals itself, it pleases Gogol to discover and study it.”

It was at establishments like the Lepre where Gogol consumed popular history, quite literally, keeping his eyes peeled for popular geniuses, for artists such as Belli. But like many things with Gogol, this didn’t last forever. The Lepre was his favorite only for a while, until he switched to the Falcone not far away. “I no longer dine at the Lepre,” he told a friend, “where you don’t always find quality ingredients. Better is the Falcone,” he said, “near the Pantheon, where the mutton rivals those from the Caucasus.”

Thinking of food as ever.

***

Indeed, thinking of food, I decided I needed to get out into Rome myself, needed to see traces of Gogol’s culinary world, remnants of his dining dens. It’s late July, a hot and sunny afternoon; Rome is inundated with its summer tourist season. Everywhere seems insanely busy. Today, I look like a tourist myself, dressed in shorts and baseball cap, armed with a camera; an intellectual tourist with a mission. I’m standing outside Gogol’s old apartment again, at via Sistina number 125, about to follow the path he likely took to dine. I begin the steady climb toward the Spanish Steps, then down the steps, past la fontana della Barcaccia, immediately accessing via Condotti. Soon the Caffè Greco appears to the right, shuttered, closed for its habitual summer recess.

Facing are numbers 9 and 10 via Condotti, a regal looking five-story building, once the Palazzo Maruscelli Lepri, with its grand entrance arch still remaining, leading you into a darkened courtyard. Gogol would have walked through this doorway, into this darkened corridor, on his way to the Lepre, situated somewhere inside. I’m lucky today, because the doorway is open. So I wander in, take a nose around; the portiere doesn’t seem bothered by my taking photos. There’s absolutely nothing remaining here of any popular eating place, zilch remnant. The tone of the present Palazzo resembles the rest of via Condotti, these days super-upscale and wealthy: Gucci is to the left, Bulgari is to the right, each either side of the entrance arch. Would Belli have pulled tongues at this in his verse? Would the flamboyant Gogol ever have worn Gucci?

I continue along Condotti, toward via del Corso, which I head down, southward. I’m on my way to Gogol’s other favorite eating joint, the Falcone, at Piazza dei Caprettari, not far from the Pantheon. It’s incredibly crowded, uncomfortably so, and I dodge people along the pedestrianized section of Corso, watching out for scooters and bikes. I make a right turn, walk southwest. The Falcone was fifteen minutes away from the Lepre. I’m not sure which route Gogol would have taken, but have a hunch he would have wanted to stroll past the Basilica San Lorenzo in Lucina. I go down via di Campo Marzio, onto via della Maddalena. In the 1840s, there’d be no need to avoid the Pantheon; you could walk in front of it unjostled, unharrassed by crowds of people: you could stop, briefly, admire, look on in awe. Those days have passed.

A couple of minutes east of the Pantheon is the Piazza dei Caprettari; on one corner is number 56, the Falcone. I never realized the site is next door to my beloved Roman pen store, the Antica Cartotecnica, which has repaired some of my old fountain pens with patient, artisanal care. Such a low-tech, independent, labor-of-love enterprise is a rarity in the center of any capital city, That’s the good news. The bad news is that there’s no more Falcone, nothing left of it, replaced by a fancy looking new restaurant called “Idylio.” Its three-course lunch menu starts at seventy euros. The restaurant, headed by the acclaimed Italian chef Francesco Apreda, has one Michelin star, and is run in conjunction with the nearby Pantheon/Iconic Rome Hotel. Gucci-clad Gogol might’ve loved to dine here, devoured probably great cuisine; at someone else’s expense, though. (“Idylio,” incidentally, is a short poem that idealizes peaceful rural life, focusing on everyday simplicity and beauty.)

It’s hard to know whether my Rome is more or less interesting than Gogol’s. Things change, have to change; he knew that, I know that. So much of Rome’s physical landscape remains, however, has hardly changed, and I’m conscious I can walk streets Gogol walked through, am surrounded by buildings that surrounded Gogol. Nothing has been razed and rebuilt—it is impossible to knock anything down in much of Rome, given its strict historic preservation laws, just as it’s impossible to build anything new. The route I’ve just taken is comparable to Gogol’s, and I feel blessed to be able to follow in his footsteps.

When it comes to content, to what lies within, Rome’s central city fabric has been flattened by mass tourism; almost everything that was once “popular” with Romans themselves has been wiped out. The center is less diverse, culturally and socially, largely emptied of popular characters, of struggling artists and poets, of émigré dissidents arguing over politics, of a cheap fare nourishing them alongside the city’s working classes. Am I disheartened? Not really. I’m just glad to be here, in a Rome that today is what it is. Gentrification has taken place. Yet compared to the other big cities I’ve lived in—London and New York especially—it hasn’t wiped out everything. My old pen store, after all, neighbors a Michelin star restaurant and where else in the world would that be the case?

To hear Belli’s verse, in its modern day incarnate, you’d have to journey elsewhere in the city, somewhere peripheral, marginal. For the moment, I’m off walking again, in what is still an eminently walkable urban environment, not despondent in the sunshine. I head across town, across the Tiber, over the Ponte Garibaldi, into Trastevere. I’m off to see the last trace of Belli, of the poet himself, a prominent statue of the man in his very own piazza—Piazza Giuseppe Gioachino Belli—posthumous immortalization. Belli was born on September 7, 1791, and died, aged seventy-two, of a sudden apoplectic fit, on December 21, 1863. He led a bizarre double-life: a shadowy clandestine writer of vernacular verse, hanging out in rough and tumble dive Roman taverns by night, reading his obscenities aloud; by day holding down a respectable job, a theatrical censor in the papal court.

Belli’s statue has a commemorative wreath on it; I’m not sure why. The poet dandy is dressed in a suit and waistcoat, his greatcoat wide open and flowing. He’s donned in a distinguished looking top hat. But the structure looks a bit worse for wear, maybe a bit unstable, because it is wrapped in a supporting brace, perhaps heralding some kind of renovation. Still, it’s a wonderful re-creation of the poet; up close you can see that his smart garb is shabby, rumpled, though his gaze is vivid, wistful. Head dipped, he’s lost in thought, crafting some risqué line in his head. The statue was consecrated in 1913 and is dedicated to Il Popolo di Roma—to “the People of Rome”—who are lovingly evoked at the back of Belli: a half a dozen or so grizzled and gnarled figures, Trastevere’s working populace, the subject matter of his sonnets. I snap away at their faces, worn but not worn-out, faces still somehow beautiful, authentically real.

It’s often said that Belli’s poetry dealt with Rome’s six “Ps”—pope, priests, princes, prostitutes, parasites, and the poor. Here we have the poor, the forgotten people in history that Gogol once spoke about—though here they’re not entirely forgotten. We could imagine these characters snuggled around the Lepre, with Gogol lurking somewhere in their shadow, smiling, laughing at the elemental verse of his poet friend, feeding Gogol’s stomach with “proper” words and scoff: “Yeah, when it comes to cooking, lard’s best…puts hairs on your chest! With bacon it’s a dream, with rarebits it’s the business, chicken too, and roasted meat, and as for stews and sauces, works a treat.”

‘Now, Doc, this fever what I’ve got,’ I went;

‘it means I have to watch out what I scoff?’

He goes, ‘One’s fine when eating wholesome stuff,

my man—one has to eat, mm? Excellent!’

So I eats, whole, some stuff, just like he said:

whole cantaloup, whole cheese, whole loaf of bread,

salami, watermelon and a hen…

Sod it, he should’ve spoken proper when

he came that day to brandy words about:

‘Scoff top-notch tucker pal, but don’t pig out’.”