There’s something about James Joyce. Once you get into him, he becomes addictive, grabs you, inspires in you some obsessive devotion, a kind of fanaticism dedicated to the man and his works, a worship. When F. Scott Fitzgerald first met Joyce in person at a dinner party in Paris on July 27, 1928 (organized by Shakespeare & Company bookstore owner Sylvia Beach), he addressed his idol as “sir,” kneeling before him, suddenly announcing that, as a tribute to Joyce’s genius, to “St. James,” he was going to throw himself out of the window. Joyce managed to catch Fitzgerald, holding him back from falling, from disappearing over the apartment’s fourth floor windowsill, saying afterward: “That young man must be mad—I’m afraid he’ll do himself some injury.”

And then there was Samuel Beckett, one-time Joyce’s personal assistant (and suitor of Joyce’s daughter Lucia), who was so beguiled by his mentor that he wore the same battered tennis shoes, in the same size, a good three-sizes too small for Beckett! And the stranger in a Zurich café, who seized Joyce by the hand, exclaiming, “may I kiss the hand that wrote Ulysses?” Joyce responded, “No—that hand did a lot of other things, too!”

I plead guilty to my own Joycean obsessions. Off-and-on for forty-odd years I’ve been reading him, appreciating him, obtaining tremendous joy from his prose and probing insights he teaches us on the human condition. I make no claims as any expert of Irish literature, only as a self-avowed amateur, with no credentials other than an enormous admiration for the man. I’m not alone in this passionate embrace. Scattered around the globe, almost everywhere in the world, thousands of people, in numerous languages, dutifully meet and participate in assorted reading groups devoted to Joyce’s books, often reading them line by line, doing so for years on end, without fail. At the Venice branch of Los Angeles Public Library, a James Joyce reading group met every month to read Finnegans Wake, eventually finishing it in October 2023, twenty-eight years after they’d begun it.

Reading Joyce has been a no-strings attached labor of love for me, nothing instrumental, a quirky devotion, including an almost squirrel-like compulsion of collecting different editions of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. I’ve got dozens of different versions on my bookshelf: “corrected” editions and abridged editions, old editions and new “special” editions, anything and everything that might have a different cover. Each time I see a Ulysses or a Finnegans Wake in a used bookstore, in an edition or version I haven’t got, with a cover that’s novel to me, I nab it, shelve it under my ever-expanding collection. Curiously, afterward, I reread this newly acquired version, making fresh annotations in it, often discovering lines, ideas, and words I hadn’t noticed before, as if the new clear copy, perhaps with a different font, helped me see things anew.

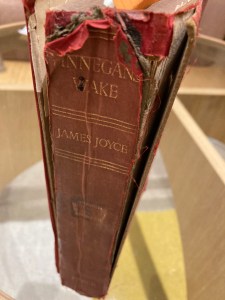

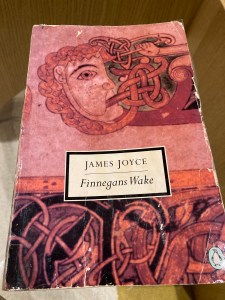

Pride of place is a 1940s Faber & Faber red hardback Finnegans Wake, a fourth printing of the text, the nearest I have to a first edition. Everything resembles the first edition anyway, a red hardback cover, quite plain. It’s all the more charming because it is literally falling apart at the seams, its pages dropping out. I love this copy but it isn’t my most affectionate version of Finnegans Wake. Dearest to my heart, is an ordinary Penguin publication, from 1999, with its Book of Kells cover and an introduction by the late John Bishop (of Joyce’s Book of the Dark fame), which I purchased at the “Murder Ink” bookstore on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

I bought it on my fortieth birthday, in the millennium year, a little gift to myself, when I lived around the corner on West 93rd Street. I remember six-years on reading with poignancy an article in The New York Times (December 20, 2006), reporting “Many Suspects Seen in the Death of a Mystery Bookstore,” as Murder Ink finally went out of business after thirty-four years of trading. The rent was increasing five percent, and the current eighteen thousand dollars a month was already crippling the small independent, devoted to crime and mystery fiction, yet not entirely. Jay Pearsall, the owner, lamented its closing. “When I see the books that I can’t order again, it’s hard. Whether it’s Finnegans Wake or Pat the Bunny, it seems impossible,” Pearsall said, “that we won’t order or sell those again.”

I also recall, after purchasing that copy of Finnegans Wake, meeting up later the same day with my friend, the writer Marshall Berman, himself a Joyce devotee—Stephen Dedalus’s “shout in the street” in Ulysses, after all, plays a pivotal role in Marshall’s own modernist masterpiece, All That is Solid Melts into Air. When I told Marshall I’d just bought a nice copy of Finnegans Wake, we went on to have a lengthy conversation about the relative merits of Ulysses vis-à-vis Finnegans Wake; Marshall always preferring Ulysses whereas I, despite also loving Ulysses, had a bit of penchant for Finnegans Wake.

Marshall liked the fact that Ulysses was a novel, challenging for sure, but its narrative could be read from start to finish, whereas Finnegans Wake was something else again, neither a novel nor readable in English. Above all, Ulysses brought together twin themes that preoccupied Marshall’s Marxist imagination, that animated his scholarship: it’s not only preeminently an urban book, it’s equally a book about urban everyday life. With this unity (and wholeness), Ulysses expressed the kind of democratic modernism that lit Marshall’s fire, the opposite of the oppressive, top-down modernization espoused by the likes of Robert Moses and Le Corbusier; Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s nighttime (and nightmare) book, would never speak to Marshall in the same way.

Ulysses voiced Marshall’s 1960s generation’s modernism, taught them where to look, how to find nourishment in a place where few modernists at the time ever dreamed of looking: in the everyday street. This is the life that Joyce’s Stephen points to with his thumb, “the apparently inchoate random shouts that drift in from the street.” Each time I pick up this edition of the Wake, with great nostalgia I think of the late Marshall, of Murder Ink, of New York’s Upper West Side, of my younger self, and of a past life gone forever.

***

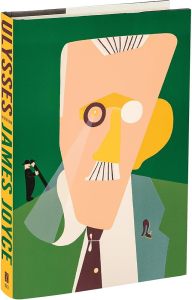

The most recent acquisition in my expanding Joyce library is a massive, blockbuster brick of a text of Ulysses, coupled with the strikingly vivid artwork of the Spanish artist Eduardo Arroyo, released by New York’s Other Press in 2022 at the hundredth anniversary of Ulysses. Arroyo wanted to illustrate Ulysses twenty-five years ago, but Joyce’s grandson, Stephen Joyce, the writer’s last living relative, had blocked it.

When Stephen died in 2021, Arroyo had his chance. Yet it had it be done posthumously, on his behalf, because the artist himself had passed away in 2018. All the while, Arroyo had privately pursued his Joycean passion, illustrating Ulysses with his brightly colored, surreal images, some almost pop art in their depiction. Joyce’s offbeat eighteen episodes have found suitably offbeat graphic representation. The net result is a rather beautiful specimen.

The publisher’s preface relates the story of Arroyo’s Ulysses, of the artist’s fascination with the Irish writer. In the late 1980s, Arroyo suffered a serious, near-death illness. But over a long recovery period he said his health ordeals were immeasurably aided by his work illustrating Ulysses. He had the intention of using his paintings to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Joyce famous day, but that wasn’t to be. It was one of Arroyo’s dearest projects, alas something he never saw come to fruition, yet he would have surely been delighted had he seen Other Press’s offering.

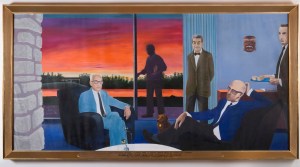

Arroyo is important for me, too, because he embodies another one of my little Joycean obsessions, helping define what my blogs in the future, those to follow over the next few months, will really be all about: a dialogue between Joyce and Marx. The artist was a chip off the old block, a Joycean drawn to Marx, a Marxist drawn to Joyce. I find the encounter inspiring. Since the late 1950s, after fleeing Franco’s fascist Spain, Arroyo moved to France, where he embraced French critical thought. He was on friendly terms with the philosopher Louis Althusser and his creative imagination was animated by Althusser’s 1960s Marxism. It would culminate in 1969 with one of Arroyo’s best-known canvases, “La Datcha,” a group portrait, neo-Soviet Socialist Realist style, of French maitres à penser, the most eminent structural and post-structuralist scholars of the post-war period.

The painting, executed with Gilles Aillaud, was a satire, with a touch of David Hockney’s Californian house motif thrown in: a late afternoon interior, a setting sun, illuminating a seated Claude Levi-Strauss and Michel Foucault, with Jacques Lacan looking on and Roland Barthes doing the honors, acting as a waiter, bringing on a tray of petit fours. Meanwhile, a ghostly silhouetted presence lurks on the outside terrace, beyond the large glass sliding door: it’s Louis Althusser, a reluctant guest or intellectual pariah, or maybe both, a Groucho Marxist not quite wanting to belong to any club that has him as a member. Decades later, in 1991, Arroyo would give us another neo-figurative parody, and the title of this brilliant and intriguing artwork squares the circle for me: “The Marxist Brothers’ Cabin, or Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.”