I don’t usually get invited to these things. I’m standing in the delightful grounds of Rome’s Villa Wolkonsky, the British Ambassador’s residence, a stone’s throw away from the Basilica San Giovanni in Laterano, full of imposter syndrome. It’s a gorgeous summer’s evening, mid-June, and I’m here as a so-called “plus-1,” the guest of a guest, to celebrate the King’s birthday—that King being Charles, the current British monarch. Everybody knows it’s not his real birthday—well, I think everybody knows—which is in November; but any excuse for Rome’s elite to have a good old bash, a rollicking time, is never forsaken. Apparently, for a long while, it’s been a British royal tradition to stage an al fresco commemoration of a monarch’s birthday, in mid-summer, usually around the solstice, when there’s a better than average chance that, in Britain at least, it won’t rain.

There are hundreds of people here, decked out to the nines, sipping champagne, prosecco, beer, and white wine, all on the house—diplomats and employees from Rome’s numerous international organizations and missions, as well as dignitaries from the Italian government. It’s the biggest “public” event of the year, a showcase for Britain, with giant Union Jacks hanging around and projected against walls. It’s hobnobbing with anybody who is anybody in Rome. I’m a fly on the wall and can’t help myself from taking photographs, snapping away at everything and everybody, at the goings on, at the marvelous garden that envelops us, at all the beautiful people around me. I make small talk with the people I meet, chatting as if I was one of them; little do they know I’m here by default, that it’s really my wife who’s the guest, and she had to get special permission for me to be allowed in.

I keep it to myself that I’ve zilch interest in British royalty, whether it’s the King’s birthday or whatever; and I’m not terribly concerned about the copious amounts of free booze on offer, either—thank the British taxpayer (none present!) for that—nor the cuisine, which mercifully is Italian. I chat with the guests and ask them, in passing, if they knew anything about the history of the place. A few knew that during the early 1940s, the villa was the wartime headquarters of the Gestapo. I enquired about whether they knew about its older Russian past, and if they’d ever heard of a writer called Nikolai Gogol.

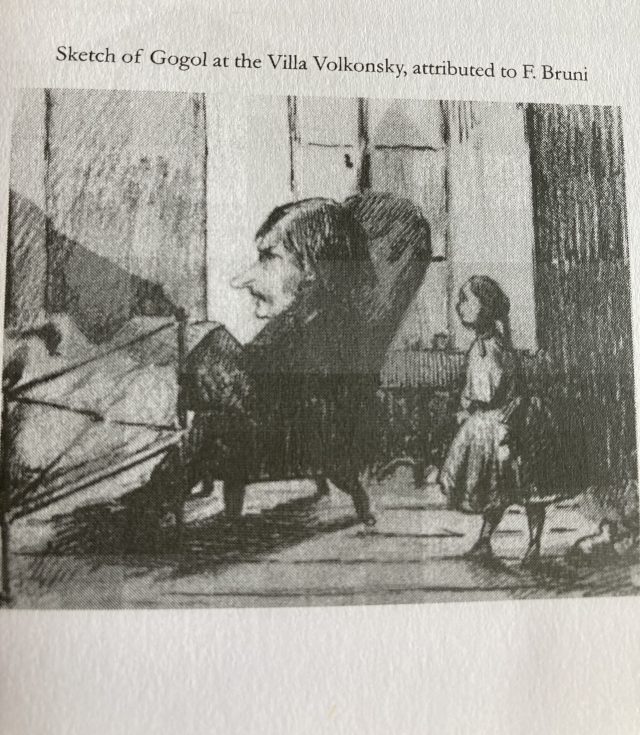

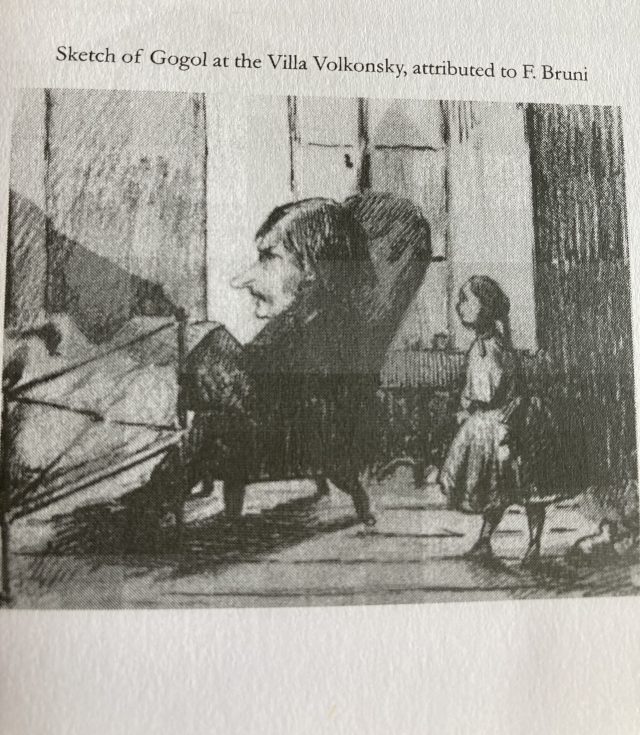

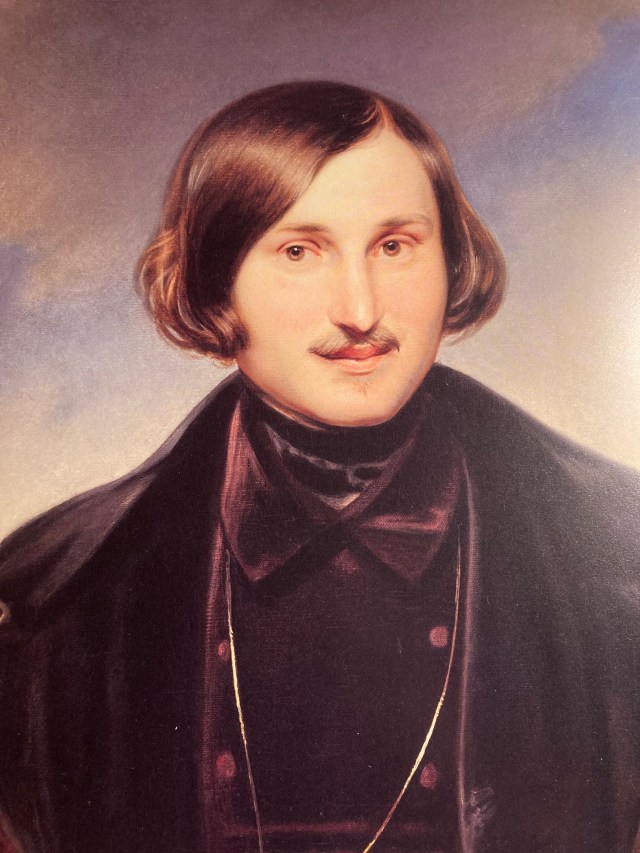

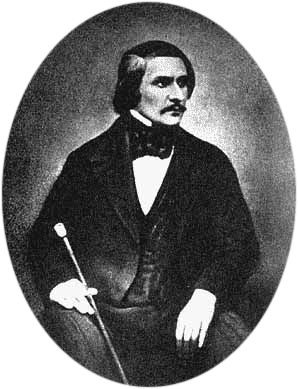

No, not really, most people said. I mentioned that the writer used to hang out here; that he was the guest of the Russian princess Zinaida Volkonsky, the eponymous founder of the villa, the woman who organized the landscaping, had the original villa built in the 1830s. This smaller property, now dwarfed by the much larger, grandiose house, the current home of the British ambassador, has a little parapet on top of one side, and on this little parapet Gogol once sat, looking over the nearby Basilica, and composed Dead Souls. There’s a pencil sketch from the early 1840s of him, sitting on the parapet’s low wall, wearing in hop hat, with the San Giovanni Basilica in the near distance. In those days, there was a clear, unbroken view of it.

Elsewhere in the villa’s grounds, Gogol lay down on grass, marveling at the bright blue Roman sky. He’d nestle up against the wall of what is the villa’s most distinctive feature: the thirty-six spans of a majestically ruined Roman aqueduct, dating from Nero’s time, from the First-Century A.D, traversing the villa’s ground. It’s a sight to behold. Under one of its arches, the princess created a cool little grotto for her friend, the famed writer Gogol, who worked there during the summer. Ordinarily, unlike this evening, Villa Wolkonsky is an oasis of peace and quiet in the incessant humdrum of the Eternal City.

***

Zinaida Volkonsky was the wife of Tsar Alexander I’s personal assistant, his aide-de-camp, Prince Nikita Volkonsky. It’s a long story of how she ended up in Rome, but she arrived here in February 1829. A year on, Zinaida purchased five-hectares of agricultural land on Esquiline Hill and proceeded over the next few years to create her very own enchanted magic kingdom, studded in banksia roses and purple coils of wisteria, lined with hedges and scores of different species of plants and trees (reputed to be near two hundred today). Meanwhile, she commissioned the architect Giovanni Azzurri to build a simple villa within three bays of Nero’s aqueduct, becoming the nucleus of the whole property, Zinaida’s summer retreat. (In the winter, she rented an apartment in the Palazzo Poli, at the back of the Trevi fountain.)

She also rearranged ancient statues and artifacts reclaimed from the tombs that were embedded in the aqueduct. “The villa itself,” wrote one early visitor, Fanny Mendelssohn, sister of the composer, “isn’t a palace, but a dwelling house built in the delightfully irregular style of Italian architecture. Roses climb up as high as they can find support, and aloes, Italian fig trees and palms run wild among capitals of columns, ancient vases and fragments of all kinds…The beauty here is of a serious and touching type.”

After the princess’s death in 1862, Alexander, Zinaida’s son (named after Tsar Alexander I), inherited the property, enlarged it, and excavated more of the Roman tombs in the ground. In the 1880s, he sold off a lot of the land to the Campanari family (Nadia Campanari was a descendent of Alexander’s), who built for themselves the larger, more regal mansion, the centerpiece of today’s villa, and Zinaida’s house became the servant’s quarter. In the early twentieth century, the villa went through a somewhat checkered period. In the 1920s, it was owned by the German government, home to their Italian ambassador until 1943. Until the end of the Second World War, the Gestapo ran the place; its torture chambers were housed in the main Villa’s basement. In 1947, two-years after war’s end, the British embassy rented the property and its grounds from the Italian government (after a Zionist bomb had destroyed the British embassy at Porta Piazza), and in 1951 Villa Wolkonsky—its “V” now transformed into a “W”—was purchased by the Brits as the official home of the British Ambassador to Italy, remaining so ever since.

Princess Volkonsky was a fascinatingly brilliant woman. Born in Dresden into one of Russia’s oldest aristocratic families, young Zinaida became the Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen of Prussia, assuming close relations with her husband’s boss, Tsar Alexander I. Alexander and Zinaida maintained a lively correspondence with each other and it was rumored they were onetime lovers. (A bust of Alexander haunts the gardens of Villa Wolkonsky today.) When she was in her twenties, Zinaida moved to Russia, settling in Moscow in 1822. Before long, bored as simply a housewife, her mansion along Tverskaya Street began hosting literary and musical salons, fast assuming notoriety—Pushkin was a regular. Zinaida adored the celebrated poet; he called her “the queen of music and of beauty.”

According to Zinaida’s biographer, Maria Fairweather (see The Pilgrim Princess: The Life of Princess Zinaida Volkonsky), Zinaida shone in the salons of Moscow and St. Petersburg. Her many talents and lively intelligence were infectious, drew admirers and followers from the arts and political life. She was the life and soul of the party, and soirées modeled themselves on the salons of pre-revolutionary Paris, with marked liberal and progressive leanings, embracing European enlightenment thought. Evenings staged readings and political discussions, performed poetry, songs, and theater, played games of charade. The princess became a veritable magnet for Moscow’s artistic circles and brains community. She was rich, beautiful, and smart, with literary talents of her own, as well as a singing voice apparently as sweet as a nightingale’s. She played an accomplished piano and harp, too, composed music and later befriended Rossini. University types and philosophers likewise began partaking, among whom were historians and critics like Stepan Shevyrev and Mikhail Pogodin, both close to Gogol.

The sudden death of Tsar Alexander from typhoid in 1825 changed things. While the last years of his reign had disappointed many liberals—serfdom, after all, was still operative and basic freedoms were thin on the ground—the incoming emperor Nicolas I was a lot more oppressive, obsessed with order, peddling a mantra of orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationality. As a counter, Zinaida participated in the Decembrist oppositional movement, coined after the attempted revolt against this new Tsarist regime, in St. Petersburg on December 26, 1825. Some of Zinaida’s friends and former associates would be exiled or imprisoned, occasionally executed—her brother-in-law Decemberist activist, Sergei, spared death, was shipped off to Siberia.

“For me,” she wrote Prince Peter Viazemsky, a close friend known since childhood, “Russia has been defiled and bloodied. I can’t bear it here, I feel stifled. I cannot, I do not wish to live peacefully in this place.” Her salons soon became clandestine gatherings of Decembrist sympathizers, conducted in the shadow of suspicion; Tsarist spies closely monitored proceedings. Russia began to feel like a prison for her, and she explored ways out, exit routes. Italy became an obvious answer, a country she’d visited often in her childhood, Rome especially.

Antagonisms with the Tsar were compounded by Zinaida’s religious beliefs, her turning away from Russian Orthodoxy in favor of Catholicism—she was a recent convert—all which prompted accusations that she was really a Jesuit agent. Thus, on February 28, 1829, Zinaida had had enough: she quit Russia for good, returning only twice for short visits, but never living there again. She exited with her elder sister Madeleine, assorted household servants, as well as Stepan Shevyrev, whom she convinced to leave his academic position and become the personal tutor of Zinaida’s son, Alexander. Punitively, the incumbent Tsar refused permission for Zinaida’s husband to travel. He would have to remain in Moscow. “What bliss,” Zinaida would nonetheless write in her journal, “to be streaming toward Italy.”

One of her first friendships in Rome at the Palazzo Poli was the popular Roman poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, who, for a while, lived practically next door, at via Poli, 91. (It’s more than likely that Gogol initially met Belli at one of Zinaida’s salons at the Palazzo, a tradition she continued to pursue with vigor in Rome.) Another early guest at her Palazzo apartment was Prince Viazemsky. Other notables were Victor Hugo, Stendhal, the American novelist James Fennimore Cooper, and Walter Scott, who, recovering from a stroke, fleeing another damp and dreary Scottish winter, stopped by, enchanting his host. Then, in June 1837, another vagabond man of letters arrived, Nikolai Gogol, with a letter of introduction to Zinaida penned by Prince Viazemsky, their mutual friend, a sort of uncle figure for Gogol, ensuring him fast-track entry into the princess’s inner court. Zinaida was thrilled; Gogol already had a reputation of a writer of genius.

The rapport between the two was immediate. Zinaida seemed one of the few women, besides his mother, with whom Gogol felt entirely at ease. He and Zinaida had plenty in common: both were deeply spiritual, each suffered periodic bouts of depression, oscillating between melancholy and excess, and both were idealists and impassioned lovers of Rome, living and breathing Italy. In 1837, the year of Gogol’s arrival, the pairing shared another event, the devastating breaking news of Pushkin’s death, at the age of thirty-eight, mortally wounded in a duel, passing away two-days later as Prince Viazemsky held a vigil around the poet’s bed. “All the joy of my life has disappeared with him,” Gogol told his friend Pletnev from Rome. “I never undertook anything without his advice. I never wrote a single line without imagining him before me—my present work [Dead Souls] was suggested by him. I owe it entirely to him. I can’t go on—I am broken-hearted.” (We know, of course, that for Gogol it was something of a case of Samuel Beckett’s: “I can’t go on. I’ll go on…”)

Gogol was a regular at Zinaida’s apartment near the Trevi fountain, and, especially, at the Villa Wolkonsky, whose gardens became one of his cherished spots to write in the whole of Rome. Zinaida’s villa soon had an added attraction for Gogol, on account of one of the princess’s guests, which revived Gogol’s spirits: a young prince called Iosif Vielhorsky, whose father was an old family friend of Zinaida’s and wanted his son, recently diagnosed with tuberculosis, to winter in Rome at the villa.

In December 1838, Gogol, hardly thirty himself, met the young prince, four-years his junior, and they rapidly fell head over heels for each other. They were inseparable all winter. Gogol was completely in love with the handsome, serious, and studious prince, who’d been at work compiling a bibliography of Russian history. The prince reciprocated Gogol’s affections, a rarity for the writer. But his health took a turn for the worst over the following spring. Gogol, grief-stricken at his partner’s rapidly failing health, came to live temporarily at the villa, at Zinaida’s behest, and he passed many hours at Iosif’s bedside, tending the sick young man. He later wrote about it, his only openly gay piece of writing, unfinished, barely three-pages long, a poetic and poignant account of his “Nights at the Villa.” (The manuscript fragment was only discovered in the archive of Pogodin after the historian’s death in 1875, and for a long while lay buried, apparently censored because of its explicit content.)

“I’m now spending sleepless nights at the bedside of my sick and dying friend Iosif Vielhorsky,” Gogol wrote Maria Balabina (May 30, 1839). “Without doubt you have heard of him…but no doubt you didn’t know his beautiful soul or his beautiful feelings or his strong character (too firm for his tender years) or his extraordinary soundness of his mind, and all this is prey of inexorable death; and neither his youthful age or right to life (doubtless a beautiful and useful one) will save him. Now I live his dying days, watch his minutes. His smile or his expression when it brightens for a moment are epochs for me, an event in my day which passes monotonously.”

“They were sweet and languid those sleepless nights,” Gogol began Nights at the Villa. “He sat sick in a chair. I was next to him. Sleep dared not touch my eyes. Silently and involuntarily he seemed to respect the sanctity of my night vigil. It was so sweet to sit beside him, to look at him. It was already two nights since we had said to each other: thou. How nearer he became to me after that! He sat still meek, quiet, submissive. God, with what joy, with what cheerfulness I would have taken on his illness, and if my death could have brought him back to health, with what readiness I would have rushed to it.”

“At ten o’clock I went down to him,” Gogol continues, ratcheting up the intimacy of his descriptions. “I had left him three hours earlier to rest a little…He was sitting alone, the languor of boredom expressed on his face. He saw me. He waved his hand slightly—‘you are my savior!’ he said to me. They still echo in my ears, those words. ‘My angel, did you miss me?’—‘Oh, how I missed you!’ he answered me. I kissed his shoulder. He offered me his cheek. We kissed. He was still shaking my hand.”

Gogol seemed to have had an epiphany that final night beside Iosif, “my life was strangely new then,” he says. “It is difficult to give an idea of it,” he says: “a charge, a fleeting fragment from my youth,” he writes, grappling to define it, “coming back to me, when a youthful soul seeks friendship and brotherhood among his young peers, and a friendship resolutely juvenile, full of sweet, almost infantile trifles, intermittent signs of tender affection, when it is sweet to look into another’s eyes, and when one is ready to make sacrifices…And all these feelings, so sweet, so young and fresh, which inhabit an irretrievable world—all these feelings returned to me. God! Why? I looked at you, my sweet young flower!” But the reality of death stared Gogol full in the face, as that young flower withered before him. “Was it necessary for this fresh breath of youth to envelop me suddenly, only to sink again into the vast cold where my feelings become numb, so that with even more distress and despair I see my life vanish. Thus the dying fire casts one final flame, illuminates the dark walls with a flickering glow, to then disappear forever and…”

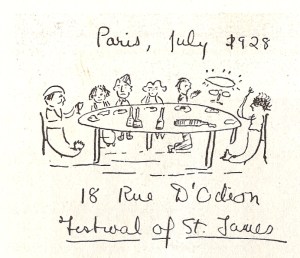

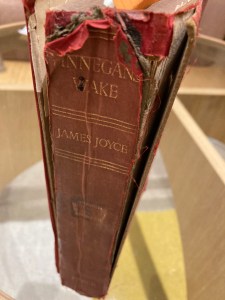

Here Gogol’s manuscript trails off, ending with an “and.” Was it intended as a longer work? An autobiographical account of his friendship and homosexuality, hitherto kept under wraps, even if he never disguised it? Yet this wasn’t a fecund “and” like the flowing “the” of James Joyce, figuring at the end of Finnegans Wake, which duly marked a beginning, a rebirth, an eternally reoccurring universe; nor was it the affirmative “yes” concluding Ulysses. Rather, Gogol’s “and” fades away into negativity, into oblivion, and marks a punctuation, the closure of a chapter of life, perhaps the conclusion of his youth, now irretrievable. Only the inexorable passage into middle-age awaited him.

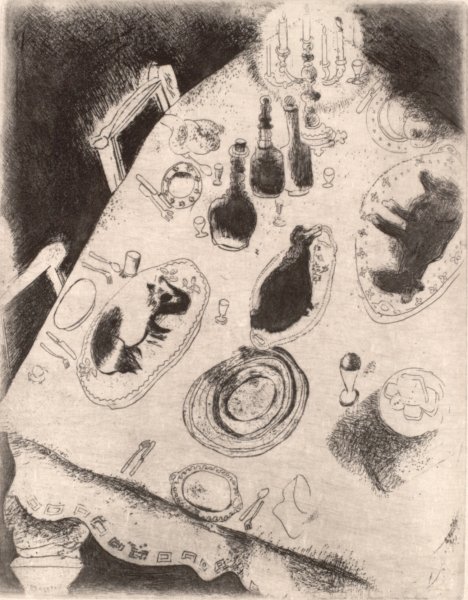

He’d henceforth bury himself in the distant land of his imagination, provincial Russia, its poshlost world of philistinism, of “bogus profundities, crude, moronic dishonesty” (Nabokov’s words), epitomized by the inscrutable Chichikov. The atmosphere of Dead Souls is full of poshlost, dreary banalities created in the tasteful bliss of Villa Volkonsky. Pushkin always said Gogol was the master craftsman who brought banalities to life, making them readable and enjoyable, worthy literary subject matter. But when Gogol read aloud early draft chapters of Dead Souls to Pushkin in St. Petersburg, rather than laughing joyfully as per usual, Pushkin became gloomier and gloomier, until, completely somber, uttered in an anguished voice: “My God, how sad our Russia is!”

After Iosif’s death on June 2, 1839, the proximity between Gogol and Princess Volkonsky dissolved. Iosif’s last hours were fraught. Zinaida said she saw the young man’s soul leaving his body, “and it was a Catholic soul.” There seemed to be then some attempt on her behalf to convert Gogol to Catholicism, but, offended, he’d have none of it. Indeed, “I will begin by saying,” he later wrote Shevyrev, “that your comparison of me to Princess Volkonskya with regard to religious exaltation…I will tell you that I came to Christ by the Protestant path rather than Catholic.”

Zinaida made a last-ditch effort to inveigle Gogol over to the church of Rome, in front of his dying friend, which caused a rift between her and the writer. Afterward, Gogol fell into a deep depression. “A few days ago,” the maudlin writer told Danilevsky, “I buried my friend, one whom fate gave me at a time when friends are no longer given—I mean my Iosif Vielhorsky. We have long been attached to each other, but we became united intimately, indissolubly and absolutely fraternally, only during his illness, alas. The man would have adorned the reign of Alexander II. The rest of those who surround him haven’t a grain of talent. The great and beautiful must perish, as all that is great and beautiful must perish in Russia.”

It took a while before Gogol and Zinaida made up, repaired their relationship, though it never would assume the previous level of intimacy; she always said this was the moment when the gloomy Gogol began his “spiritual education,” spending hours on the villa’s terrace, gazing at the sky, and at the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano. He and Zinaida undertook their own private religious mania, eventually parting their spiritual ways, their fanaticism taking on radically different forms. He, Maria Fairweather notes, “began to see his work as part of a process of Russia’s redemption…she of her special mission in the general regeneration of the world.”

A decade after Gogol’s passing, his “Overcoat” took on a dramatic twist. One winter’s day in February 1862, Zinaida was making her way home on a particularly bitterly cold Roman day. She spotted a beggar woman shivering on the street. Pitying her, Zinaida offered her petticoat and continued on. When she returned home, thoroughly chilled to the bone, Zinaida caught a cold herself, which turned feverish; several days on, she was gone, aged seventy-three.

***

Gogol loved Villa Volkonsky, but it was hard for me to comprehend this, to appreciate it fully, during the night of the King’s birthday, this deep past, the story of Gogol and the princess at the villa. Yet the more I read about his time there, the more I felt an inexorable urge to return, to see the place under calmer circumstances, in a quieter, more reflective mood, as Gogol would have experienced it. More particularly, I wanted to stand in the Villa’s grounds, get inside the original villa, if I could, discover Gogol’s grotto, if it still exists, look out at the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, as he had looked at it, look out over Rome, over Russia, up at the sky.

Over the proceeding months, I inveigled my wife to pull a few strings. She said she’d get in touch with Fiona, a colleague she knows at the British Foreign, Commonwealth Development Office, explaining my request. Fiona told my wife I should reach out to Terry, the villa’s Residence Security Manager, which I did, and, in time, all was arranged: on a gorgeously sunny, mild November afternoon, I stood at the iron-grilled entrance of the villa again, passing soldiers from the Italian military guarding the outside. At an internal sentry post, I was buzzed in through two gates, the second slowly opening as the first slowly closed. Terry greeted me on the inside. He said he was born down the road yet sounded like he’d been raised in London’s east end. Terry explained he couldn’t show me around as something had cropped up, but instead one of the Italian security guards, Giovanna, speaking excellent English, would supervise my tour.

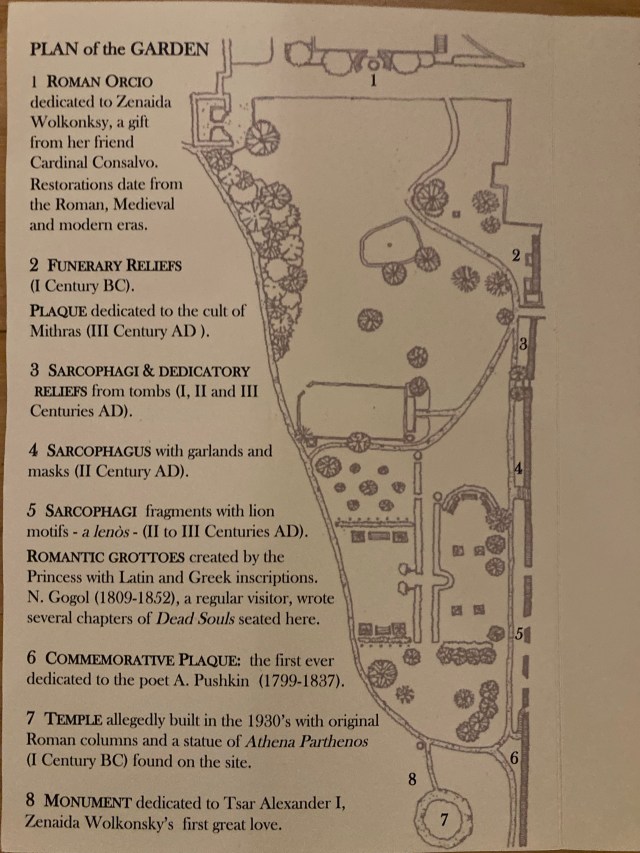

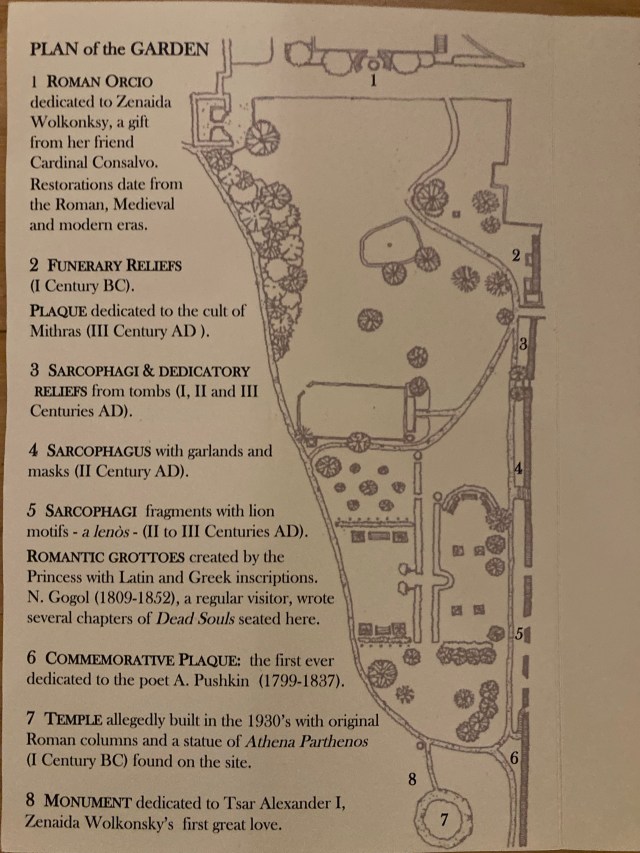

Giovanna, in her late fifties, was a delight, telling me, apologetically, that she’d been on the job at the villa for only two days, having worked for over thirty on security at Fiumicino airport; it’s the same contract company deployed at the villa (ADR Security). She didn’t know anything about the villa’s history, nor about Gogol, but said she was excited to walk around with me, happy to be out of her office confinement. Both of us followed the informative “Plan of the Gardens,” a little map and guide Terry had equipped us with, produced by the UK government. Without further ado, we were off on our afternoon’s exploration, and what an afternoon!

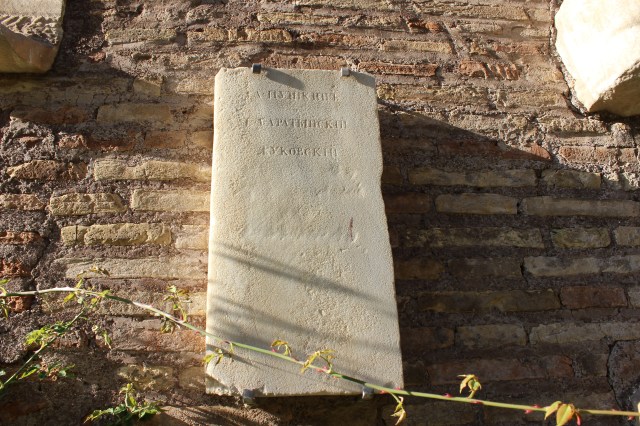

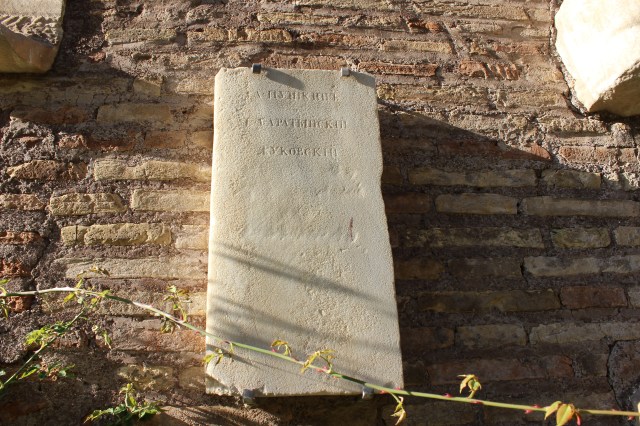

Alas, I couldn’t enter Zinaida’s original villa, Terry said, because it is occupied by British diplomats, who live inside the converted apartments, and, as private residences, the building was off-limits to me. At first, my heart sank but soon I realized the gardens themselves were a cornucopia of treasures, especially Gogol’s grotto. Created by the princess, with its Latin and Greek inscriptions, the granite bench had Gogol sit scribbling lines of Dead Souls, in peace and tranquility, in the freshness of his orange-colored niche. A headless, life-sized statue of a woman stood in the middle (point to note: most, if not all, of the thousands of the ancient statues scattered around are headless). Needless to say, thrilled, I took plenty of photos. Nearby, to the left, adorning Nero’s aqueduct, were fragments of lion motifs, little sculptures dating from the Second and Third Centuries A.D. A bit further along from Gogol’s grotto, also on the aqueduct’s wall, was a marble plaque in Russian commemorating Pushkin, something I never knew existed, beautiful in its simplicity, glistening in the magnificent light enveloping the gardens.

I felt very privileged: a private viewing of these wonderfully preserved artefacts, of the pristine green lawns in their radiant glory—with turf apparently shipped in from Britain, and, in a far corner, near the temple (built in 1931), we came across that bust of Tsar Alexander I, looking a bit ruined yet still remarkably stately; the “Plan of the Gardens” says he was Zinaida’s “first great love.”

I passed a lovely hour in the grounds, and in Giovanna’s company, who told me she was born in Sardinia though grew up from an early age in Ostia, a working-class coastal town (site of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s murder) a half-hour or so away (traffic permitting). Giovanna seemed pleased when I mentioned that my last book was on the Sardinian Antonio Gramsci. As we headed toward the gate, the villa’s resident cat, Elizabeth, joined us (no guesses after whom she’s named), and before long I had passed through the security gates again, exiting onto via Ludovico di Savoia.

Five minutes later, zipping along on a Lime scooter, I was back home at my apartment, shaking my head in wonderment, in disbelief that I live here, in Rome, and just up the road, quite literally, had been where Gogol wrote a good chunk of Dead Souls. It was kind of amazing, and for a while I reflected on this amazement. On that stone seat, surrounded by beautiful gardens, in a romantic grotto nestled in Nero’s aqueduct, not far from here, Gogol sat, and there he wrote. I thought about what the American critic (and Gogol fan) Edmund Wilson had said when visiting Rome in the mid-1940s, a century after Gogol’s time, marveling in letter to another Gogol fan, Vladimir Nabokov, about how Gogol invented Chichikov “in clear Italian light—all that world of Dead Souls seems so far away.”

In a sense, it couldn’t have been truer. In another sense, thinking about it now, having seen what I’d seen, having felt it, perhaps the provincial Russian estate of Manilov in summer is closer to the Villa Wolkonsky than you might think. “Over the master’s house,” Gogol wrote, “were strewn, English-fashion, two or three flower beds with bushes of lilac and yellow acacia. Five or six birches in small clumps raised their small-leaved tops here and there. Beneath two of them could be seen a gazebo with a flat green cupola, blue wooden columns and an inscription: THE TEMPLE OF SOLITARY REFLECTION.”

Was Gogol thinking of Zinaida and her villa when he had Chichikov address Manilov’s wife? “‘Madame, here’, said Chichikov, ‘here is the place—and with that he put his hand over his heart—‘yes, it is here that the agreeableness of time spent with you will abide! and believe me, there could be no greater bliss for me than to live with you, if not in the same house, then at least in the nearest vicinity. Oh! that would be a paradisal life!’ said Chichikov, sighing.”

Somehow, in this bliss of the villa’s paradisal life, Gogol created the scoundrel Chichikov, the very definition of mediocrity, “neither too fat nor too thin, nor could he be described as either old or young.” His arrival caused no commotion in the town, says Gogol, nor anything special, “except for a few comments exchanged between two peasants standing by the entrance to a tavern opposite the inn, which, as a matter of fact, concerned the carriage rather than the occupant.” Yet Chichikov’s real forte resided in the fact that he is a deceiver and fraud, a cagey conman who’d have functioned effortlessly in our own times, which might be Gogol’s deeper point. Chichikov’s lies and deceptions would gladly make our world go around.

“The newcomer,” says Gogol, “seemed to avoid saying too much about himself, and, if he did, it was only in general terms and with marked modesty.” In his conversations with the town’s dignitaries, “he displayed great skill at flattery.” After a while, everybody who makes his acquaintance heartily agreed that he is “an extremely pleasant fellow”—even those who seldom have a kind word for anyone. “Such was the general impression made by the newcomer,” writes Gogol. “It was quite flattering and lasted until a strange peculiarity came to light. But we are soon to learn about this matter, which all but threw the entire town into confusion.”

Chichikov identifies the vicinity’s largest landowners, and one-by-one pays them a visit. He politely butters them up, and they wine and dine him and he’s full of compliments and not without a certain charm. When he raises the matter of dead souls to Manilov, the latter is speechless: he “opened his mouth and his pipe dropped to the floor. He remained with his mouth gaping for several minutes.” It’s another “dumb scene,” resembling the finale of The Government Inspector. Manilov hadn’t heard anything stranger, “more unusual than any that had ever reached human ears before.” Why would anybody want to buy dead souls? The souls in question are serfs, and every landowner who has an estate of any significance has a posse of serfs laboring for them. The richer the landowner, the more serfs they own, the more “souls” they possess, an emblem of wealth and standing in the region.

Yet these souls must be documented and are subject to a poll-tax. The tax system operative in those days was desperately skewed, because the squires themselves were exempt from paying taxes: it was the serfs who paid up! All the landowners did was assume responsibility, collecting taxes from their serfs, and then sending them off in accordance with the number of living serfs at the time of the last census. If the serfs died before the next census, landowners themselves remained liable for their poll tax. Thus, selling a dead serf liberated them of the burden of having to pay, and the new owner became responsible for payment. As such, why would anyone be stupid enough to want to buy “dead souls” and become liable for their poll tax? It seemed utterly bizarre, preposterous, hence Manilov’s gaping mouth, his dumb scene. It isn’t clear to anybody, and it’s only much later, near the end of the first part of the finished Dead Souls, that Chichikov’s motive becomes clearer.

So it goes that Chichikov does the rounds of the local squires, driving a hard bargain, acquiring their dead souls at a peppercorn price. That is until he encounters Nozdrev, a wily, ruffian squire, an uncouth, aggressive, and crooked landowner, a lying businessman; it takes one to know one. Chichikov had met his nemesis. By then, he had purchased hundreds of dead souls and, in the eyes of the town’s elite, is a proven big shot, a rich gent who is planning to snap up a large estate, somewhere nearby, where his apparently living souls would graft. When the legal exchange is signed and sealed at the town hall, nobody mentioned that the listed souls were in fact all dead, and nobody apparently cared.

And yet, when Chichikov attempts to obtain Nozdrev’s dead serfs, the latter smells a rat. “Why d’you want ’em, then?” he enquires. Chichikov hadn’t been confronted like this before and didn’t know how to respond. He claims he wants to marry somebody and needed the souls to emphasize his social standing, to convince the bride’s father of his worth. “You’re lying!” Nozdrev says. “You’re a liar, friend!” And so he was. “I know it very well,” Gogol has Nozdrev exclaim, “you’re a monumental fraud.” Right again. Chichikov quickly realizes it’s a grave error to have set eyes on this character Nozdrev; he’s set to scupper Chichikov’s best laid plans. “He will gossip, lie, and spread rumors,” muses Chichikov. “It wasn’t good at all…his business wasn’t of a sort that could safely be entrusted to a man like Nozdrev.”

It’s all true, because bit by bit we discover Nozdrev effectiveness at spreading false news about Chichikov. Lies becomes a liar’s downfall. Nozdrev doesn’t only spill the beans about those acquired souls being in reality dead—not false, of course—but that Chichikov is really after the governor’s daughter, that he plans to abduct her, which is not true. Busybodies soon arouse the whole town and before long, “everything was astir,” Gogol says. It took a little more than an hour before the fake news to run rampant, to assume verisimilitude. So it became fact that Chichikov planned to elope with the governor’s daughter. “Amplifications, additions, and revisions were added to all this,” says Gogol, “as it trickled down to the humbler parts of town.” Who needed social media with hearsay like this!

“No one actually knows who Chichikov really is.” Even Gogol himself starts to wonder who this person is he’s created; and then, near the book’s end, we find out, in a sort of author’s confession. “I haven’t chosen a man of virtue for my hero,” admits Gogol. Our narrator is tired of positive heroes, he says, of virtuous men, who usually figure as hypocrites anyway, “and now I feel the time has come to make use of a rogue. So let’s harness him for a change.” Is Gogol talking about us, even about himself? Maybe I’m Chichikov, he says at one point. Chichikov is a serial loser that seems to succeed by taking everybody in. He hops from one failing to another, yet seems to gain esteem each time, finding his way through it all, showing at least one talent: resilience, overcoming blows with his amazing drive to succeed, believing the lies he tells and the yarns he spins. He’s a man of our age, all right!

Entering middle-age, Chichikov concocted the hairbrained idea of buying up dead souls, knowing that estate owners would be only too happy to let him have them, releasing them of their per-capita taxes. “If I offered, let’s say, a thousand rubles for the lot,” Chichikov reasons to himself, “I could get a mortgage from the National Treasury of about two hundred rubles per soul, which would bring me around two hundred thousand rubles!” We might say that Chichikov hatches a scheme to revalorize dead labor. That’s the way I like to view Dead Souls, as something akin to what Marx used to call dead labor. For that’s what dead souls essentially are, living-labor that created value, yet now have expired, becoming dead labor, no longer value creating—or are they? Because, here, we can see how a title to dead labor is in fact something that helps accumulate capital.

“The over-worked die off with strange rapidity,” Marx said in Capital. “But the places of those who perish are instantly filled, and a frequent change of person makes no alteration to the scene.” When Marx spoke about “dead labor” he wasn’t always, despite this quotation, speaking literally. More usually, dead labor for him represented past labor accumulated in machinery and technology, those acts of labor embodied in means of production that now set in motion living labor—an actual human workforce. Marx said these instruments of labor “confront” the worker during the labor process and come to dominate, “soaking up” living labor; dead labor thus sets the rhythm and dictates of the conditions of living labor. Marx’s prose in Capital is graphic: “dead labor, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor.”

Chichikov is vampire-like in his thirst for dead souls, for dead labor—which, for him, came to dominate living souls, dominate in the sense that instead of owning real capital he could valorize fictitious capital, much handier as a pure financial asset than any living soul. “Best of all,” Chichikov says, “is that the commodity to be transacted is too unusual to raise anyone’s suspicions.” He knows all-too-well how the art of the deal reigns. We’ve exhausted the virtuous man, Gogol reminds us; virtue doesn’t seem to get you far in this world.

Near the end of Part 1 of Dead Souls, Gogol’s narrator intervenes again, addressing us, his readers, taunting us, challenging us, posing questions of us and about the book we’ve just read, as our narrator had recounted—as Gogol had written it. It’s a strange intervention, self-exoneration. “The reader ought not blame me,” he says, “if the people we’ve met so far aren’t exactly to their taste: blame Chichikov, for we must follow him wherever he decides to go. “What triumphs and failures he’ll experience, how he’ll cope with even more difficult obstacles, how great will be the stature of the characters who’ll appear in the narrative as it gains momentum, how its horizon will expand, and how it’ll acquire lyrical overtones—this the reader will discover later.”

But Gogol doesn’t give us a chance to find out: in the intervening years—the five years that would pass since Part 1 of his novel—he’d destroy much of its continuation. Instead, he leaves us with Chichikov hurtling out of town in his carriage, fleeing the gossipers, the rumor-spreaders, watching the houses, the walls, the fences, and the streets skipping up and down as they recede “and God alone knew whether he would see them again in his lifetime.” And then the tops of pine trees float away in the mist, the sound of church-bells fade, and, finally, the endless horizon opens up. “The whole road is flying,” Gogol signs off, famously, “everything is flying…And you, Russia—aren’t you racing headlong like the fastest troika imaginable?…And where do you fly to, Russia? Answer me!”

*Coda: In 1984, Russian TV audiences had the chance to watch Mikhail Schweitzer’s marvelously other-worldly rendering of Dead Souls, a lot filmed in soft focus. Shown in five-parts, Gogol himself starred—well, a disturbing lookalike actor played by Alexander Trofimov, narrating his own book from Rome (we know it’s Rome because of the rooftops glimpsed out of the open window, together with the sound of church bells). There’s a deliciously camp and risqué (for Soviet TV) scene, early on in the first episode, of a boot fetish lieutenant preening and admiring his polished leather high footwear; it’s a genuinely hilarious extract of the close of chapter VII in Gogol’s actual text.

When everybody at the inn is asleep, a single light remains on, as the lieutenant from Ryazan is mesmerized by his pair of new boots, inspecting them in the mirror, unable to take them off and go to bed. “The boots were so wonderfully constructed,” Gogol writes, maybe revealing his own boot mania, “that he kept lifting a foot again and again, to examine the beautifully shaped heel.” In Schweitzer’s film, this scene becomes even funnier because he has Chichikov, in an adjacent room, peer through a secret crack in the wall, eavesdropping on the lieutenant’s private fetish; Chichikov seems moderately turned on by his peep show. (Chichikov himself wears mascara.) One can imagine Russian audiences rolling about with laughter, chinking glasses of vodka, amazed at what they were watching on the box…

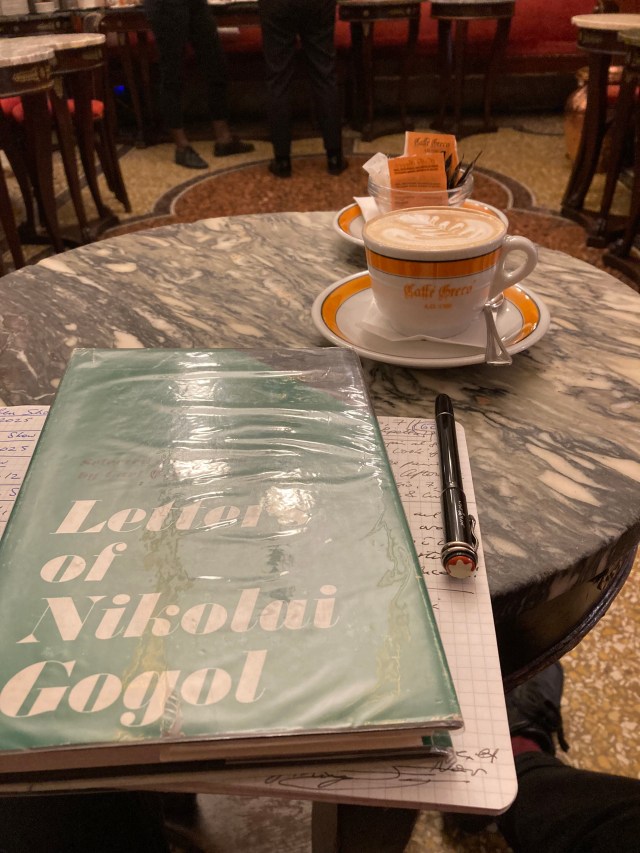

This pursuit for pens has assumed a private passion, replacing my former habit of worming in used bookstores. My exploration of cities becomes a pretext for a quest for a vintage fountain pen. I’ve found some real gem Montblancs over the years, and often not as expensive as you might imagine with such a luxury brand, several from Rome’s wonderful Borghetto Flaminio Flea Market, a little north of Piazza del Popolo. The used Montblanc market is populated by a markedly different consumer than the business types who purchase pens new at glitzy high-end boutiques, and for whom Montblancs are status symbols rather than passions about writing. Part of the joy of the pursuit for the used pen is the thrill of anticipating how it might write; it’s also the expectation of finding something, or of it finding you, as Breton might have said, of it happening at a bargain in a neighborhood you’d previously not known.

This pursuit for pens has assumed a private passion, replacing my former habit of worming in used bookstores. My exploration of cities becomes a pretext for a quest for a vintage fountain pen. I’ve found some real gem Montblancs over the years, and often not as expensive as you might imagine with such a luxury brand, several from Rome’s wonderful Borghetto Flaminio Flea Market, a little north of Piazza del Popolo. The used Montblanc market is populated by a markedly different consumer than the business types who purchase pens new at glitzy high-end boutiques, and for whom Montblancs are status symbols rather than passions about writing. Part of the joy of the pursuit for the used pen is the thrill of anticipating how it might write; it’s also the expectation of finding something, or of it finding you, as Breton might have said, of it happening at a bargain in a neighborhood you’d previously not known.