Gramsci saw the whole of the Italian “South” as a kind of goblin, as a character who got and keeps getting a bad rap, like Rumpelstiltskin. In late 1926, a month or so prior to his arrest, he was at work on a long essay about the Italian South, Alcuni temi della questione Meridionale—Some Aspects on the Southern Question. The piece was never completed; it was rudely interrupted; and while there’s a lot left dangling, there’s plenty for us still to glean. Gramsci was addressing his Marxist comrades, notably comrades from the north, in a tone that’s critical, enquiring, taking to task all camps, typically trying to get at the truth—warts and all. Gramsci chastised a Right northern bourgeoisie as well as a Left industrial proletariat, northern Marxists as well as southern liberals, workers from the north as well as a gentry from the south.

Point is that all this is voiced by a lad from the south. Gramsci’s political awakening occurred in the north, yet his cultural allegiances always rested with the south. He grew up in peasant society, spoke local Ghilarza dialect, and probably didn’t hear Italian itself until he reached grammar school; and then, in Turin, through his college professors. As a poor, set-apart kid, encountering official Italian was likely both a source of liberation and a lesson in officialdom, the tenor of a ruling class authority he was out to smash.

So part of Gramsci’s struggle was to invent not only a different kind of Marxism, but also a different kind of language, a different political register that spoke neither raw dialect nor elitist Italian. In a sense, amalgaming the two interested the linguist in him, mixing the language of the countryside with that of the city, reconciling the expressive powers of vernacular with the sobriety of reason, converting a commonsense into good sense; a Marxism neither flaky idealism nor iron-law materialism yet something else again—a concrete, authentic, philosophy of praxis sensitive to place, culture, and tradition. There’s a lot more there there in his Marxism.

We can witness this flowing through “Some Aspects on the Southern Question.” He’s especially skeptical of how his factory council comrades want to resolve southern “backwardness.” By smashing the capitalist factory autocracy, they say, smashing an oppressive state apparatus, a workers’ state would then smash the chains that bind peasants to the land. Taking over industry and the banks would swing the enormous weight of the state bureaucracy behind the peasants, helping them vanquish in their struggle against southern landowners.

Gramsci doesn’t buy into this northern patronage, into the communist “magical formula” (as he labels it). He doesn’t believe the solution to the “Southern Question” lies in the hands of a northern workers vanguard. Northern communists, he says, have more in common with their bourgeois antagonists, a lot more than they consciously appreciate. They’ve been “unconsciously subjected to the influence of bourgeois education, to bourgeois press, to bourgeois traditions.”

“It’s well known,” Gramsci says, “what kind of ideology has been disseminated in myriad ways among the masses in the north, by propagandists of the bourgeoisie: the south is the ball and chain which prevents the social development of Italy from progressing more rapidly; southerners are biologically inferior beings, semi-barbarians or total barbarians, by natural destiny; if the South is backward, the fault doesn’t lie with the capitalist system, but with nature, which has made southerners lazy, incapable, criminal and barbaric.”

Left-wing positivism has often reinforced southern inferiority: “science was used to crush the wretched and exploited, but this time it was dressed in socialist colors and claimed to be the science of the proletariat.” Factory workers and Marxist intellectuals, Gramsci says, have to rethink this approach so that the Left can become politically effective throughout all Italy. Proletarians and their leaders “must strip themselves of every residue of corporatism, every syndicalist prejudice and incrustation,” he says. They need to overcome distinctions between one trade and another, between factory workers and artisans, industrial laborers and toilers on the land, between the city and the countryside—between a north and south embedded in peoples’ heads.

Spatial antagonisms—urban versus rural, north versus south, etc.—tend to occlude basic class questions, says Gramsci, and one of the biggest problems here is organizing. In the south, urban forces are subordinate to rural forces, the city kowtows to the countryside. In the Mezzogiorno, the countryside is less progressive than the city; but southern urbanism, unlike its northern counterpart, isn’t industrial, and can’t be organized in the same fashion as a giant car plant; the culture and history of Naples is different from Turin and Milan. And yet, given the dominance of the industrial north, and the greater leverage of its factory workers and unions, the latter has to convince southern rural and urban working classes that they’re all brothers and sisters in the same struggle.

The schism between city and countryside, in other words, is much more nuanced than crudely meets the eye. Indeed, Gramsci warns about the ideology of appearances. “The relations between urban population and rural population,” he says, “aren’t a single, schematic type.” Figuring out their dialectical specifics, as well as fulfilling an educative and directive role, is the task Gramsci ascribes to “organic intellectuals,” a species of thinker and activist different from “traditional” intellectuals: the latter, he says, operate more conciliatory—lawyers, doctors, notaries, teachers, priests, bureaucrats, and technocrats—professionals who, wittingly or unwittingly, usually prop up the status quo rather than tear it down. Left organic intellectuals, on the other hand, feel the elemental passions of “the people” and become “permanent persuaders.” They critically explain the movement of history, as well as the working class’s interests in that movement. In Italy, as elsewhere, organic intellectuals help forge a “national-popular collective will.”

***

Gramsci’s health worsened toward the end of 1933. Sister-in-law Tatiana and longtime Gramsci friend, Piero Sraffa, a renowned economist at the University of Cambridge, made frequent appeals about getting him moved and better cared for. After Turi’s prison doctor also recommended a transfer, the fascist government eventually authorized Gramsci’s shift to Professor Giuseppe Cusumano’s health clinic in Formia, a coastal town 100 miles south of Rome. Although still under police surveillance, Gramsci could go out for occasional short walks, accompanied by an approved individual. Every Sunday, Tatiana journeyed down by train from Rome, and together they’d walk along the beachfront; sometimes brother Carlo came, and a few times Sraffa himself, from the UK.

Gramsci’s poor health, though, meant he couldn’t fully benefit from his newfound conditional liberty. A cleaner at the Cusumano clinic recalled her initial glimpse of the new patient: “small, hunchbacked, wrapped in a black Sardinian shepherd’s cloak, between two policemen.” “I was disappointed,” she said. “They told me Gramsci was the leader of the communists, a revolutionary, and I’d imagined him tall, imposing, not so small, minute, tired; but his eyes were clear, alive, penetrating, they dug into you. It was clear he was an extraordinary man.”

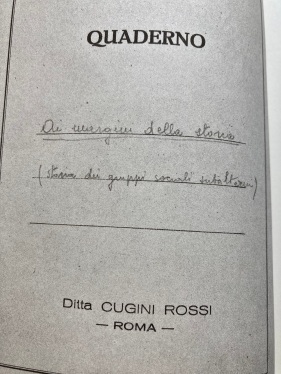

Significantly, Gramsci was now allowed access to all his notebooks at the same time—at Turi, he was only able to see five in one go. Thus he began recopying old raw notes, modifying them, expanding them here, deleting them there, collating them, grouping them together into “special” single topic themes. In July 1934, Gramsci started to assemble Notebook 25, Ai margini della storia [storia dei gruppi sociali subalterni]—On the Margins of History [The History of Subaltern Social Groups], bringing his scattered writings from Turi together into a 160-page composition notebook, larger-sized than he typically used before, and a different brand—”Ditta CUGINI ROSSI ROMA.”

Evidently, he’d anticipated a bigger project—on slaves and plebians from ancient Roman and medieval Italy, on peasants and proletarians, on subaltern social groups’ connection to history and economics, to commonsense and folklore, to spontaneity and intellectuals—on the potential for them acquiring “hegemony”; developing their own autonomous political consciousness; revolting against the bourgeoisie; taking their subordination out of the realm of civil society and politicking around the state, maybe one day becoming a state themselves. There was enough material here, Gramsci felt, to constitute an extended monograph, kickstarted with that essay on the southern question almost a decade earlier. He’d left the first ten-pages of notebook 25 blank, readied for an introductory text and a summary index that, with ever-failing health, he never managed to create. Hence Tatiana marked Quaderno 25 (XXV) “Incompleto.”

Gramsci was an original, a chip off the old block, the first Marxist ever to mobilize the term “subaltern.” He never knew it, of course, but he single-handedly invented a whole new discipline: “Subaltern Studies,” with its emphasis on the ignored and neglected in western history, as if it were the only History. Now, Gramsci’s southern question has enlarged to embrace the global south, a southern global imagination, those excluded “from historiography of the dominant classes, although protagonists of real history.”

In 2021, Columbia University Press thought Gramsci’s treatment of subaltern social groups sufficiently important to warrant English translation (by Joseph Buttigieg and Marcus Green), and a “critical edition” of notebook 25, combining allusions to subalternity from other Gramsci notebooks. The project would compensate for the short shrift Selections from Prison Notebooks initially afforded the topic—with no index entry for a thematic so personally and politically vital to Gramsci, the dark-skinned, hunchbacked goblin, a pariah from a culture different to the dominant. He empathized with subalterns, knew them, recognized them, because he came from them, recognized himself in them.

“Often,” Gramsci says, “subaltern groups are originally of a different race (different religion and different culture) than dominant groups, and they’re often a mixture of races…The question of the importance of women is similar to the question of subaltern groups… ‘masculinism’ can be compared to class domination.” Subaltern classes, he says, are portrayed “as having no history,” “people whose history leaves no traces in the historical documents of the past.”

Subalterns have to prize themselves free from the subjection dominant forces impose upon them. They also have to prize themselves free from their own passivity. This is hard, Gramsci admits, because “we’re all conformists of some conformism of another, always man-in-the mass or collective man”; we all belong to a particular social grouping that transmits, for better or for worse, its own uniform mode of thinking and acting. To that degree, one needs to be hard on oneself as well as on one’s antagonists; one needs to struggle against the world while struggling against oneself, internalizing at the same time as externalizing rebellion.

“When one’s conception of the world isn’t critical and coherent,” Gramsci says, “but disjointed and episodic, one belongs to a multiplicity of mass human groups.” The trick “is to criticize one’s own conception of the world,” to make “a coherent unity and to raise it to the level reached by the most advanced thought in the world.” “The starting point of critical elaboration,” he says, “is the consciousness of what one really is, and ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date which has deposited in you an infinity of traces without leaving an inventory.”

The subaltern, more than anybody else, needs to know themselves connected to the historical process, know themselves as being on the receiving end of this process, know how they’ve been undermined by that process, and sometimes how they’ve undermined themselves in that process. One problem is that even when subalterns rebel, “they’re in a state of anxious defense.” “Every trace of autonomous initiative, therefore, is of inestimable value.” (Gramsci captures here the perennial condition of the modern Left: in a state of anxious defense.)

The other problem is that when subaltern groups aren’t looked down upon, scorned and abused, they’re patronized, treated as “humble.” It’s a characteristic attitude, Gramsci says, of a lot of intellectuals, even well-meaning ones. For the Italian intellectual, “humble indicates a relationship of paternal protection, the ‘self-sufficient’ feeling of one’s own undisputed superiority; like the relationship between two races, one superior, the other inferior; like the relationship between adult and child in old schooling; or, worse still, like the relationship of a ‘society for the protection of animals’ or like that of the Anglo-Saxon Salvation Army toward the cannibals of Papua.”

It’s sensibility in stark contrast to Dostoevsky’s, Gramsci says, as depicted, for instance, in The Insulted and Injured (1861), a novel never terribly well favored by Dostoevsky afficionados, his first after Siberian exile. But Gramsci had spotted something in it that struck a suggestive political chord. “In Dostoevsky,” he says, “there’s a strong national-popular feeling, namely, an awareness of a mission of the intellectual toward the people, who may be ‘objectively’ composed of the ‘humble’ but must be freed from this ‘humility,’ transformed and regenerated.”

Gramsci doesn’t mention it by name, but this idea of “a mission of the intellectual toward the people” emerged in Russia during the early 1860s, expressed most fervently in the “Narodnik” movement. Young progressive urban intellectuals, dressed in simple peasant garb, fled cities and went “to the people,” canvasing across the countryside, inciting revolt against Tsarist rule. They lived amongst the people, merged with the people, taught them, learned from them, and tried to fight for their collective interests. Gramsci saw in the Narodniks a model for catalyzing revolt, a prototypical representation of the organic intellectual, somebody who could help the subaltern speak without ever putting words in their mouths.

***

The Cusumano clinic was a dreadful place for Gramsci. His letters indicate shoddy treatment. Tatiana claimed her brother-in-law’s health went further downhill. He had to endure incompetent medical care, she said, inedible food, and no hot water for bathing. He suffered the “neglect, indifference, indolence” of the clinic’s staff. Tatiana was damning. Adding to existing health woes, Gramsci developed a hernia, requiring the surgery he never got. His nervous and digestive systems were kaput. He was feverish, seized by tremors. Even holding a pen was a chore. Urinal infections meant frequently pissing blood.

And he couldn’t sleep: “The Cusumano family has arrived,” he told Tania (July 22, 1935). “Over my head there’s a continuous to and fro from five in the morning until midnight… I’m a sick person and every slightest rustle agitates me enormously. I will recover from many ailments and precisely from those which at the moment are the most tormenting.” “I am absolutely determined,” he added, “to leave the Cusumano clinic and as soon as possible.”

I was intrigued about this clinic in Formia, long since shutdown. I understood the building still stood, overlooking the beach, and so, one Sunday morning, early March, on an unseasonably blustery, rainy day, I got into my car and made the two-hour trek down from Rome. Waves crashed into Formia’s waterfront wall; walking the half a mile or so from the center of town, along via Appia Lato Napoli, toward number 30, necessitated a salty sea spray drenching. Then the former clinic appeared, a standalone, six-story cream structure, a lot smaller than I’d imagined, with decorative pink cornices, green shutters, and small balconies. Once it would have had a certain grandeur, an architecture suggesting 1920s construction. In Gramsci’s day, it would have felt almost new. In our day, it’s a condo apartment complex, opposite a gas station. Although occupied, most of the windows are shuttered up, maybe for the season, and overall the place strikes as in need of a little care and attention, a rehab and refresh.

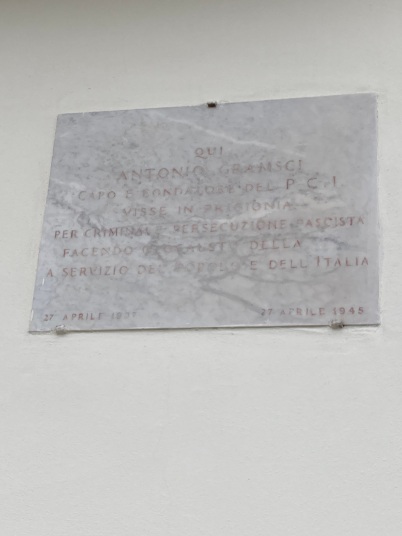

I peered through a glass main doorway, into a tired looking entrance foyer, with plant pots and ornately patterned brown tiling. Doubtless the exact same floor once walked upon by Gramsci, wrapped in his Sardinian shepherd’s shawl. A large arched window at the far end, with traces of its former splendor, opens onto sea, offering an impressive view; yet, again, today, everything seems worn and musty, its better days behind. At the upper right of the entrance doorway, on the outside wall, a faded marble plaque, inaugurated on April 27, 1945, the eighth anniversary of Gramsci’s death, commemorates his miserable Formia sojourn.

QUI

ANTONIO GRAMSCI

CAPO E FONDATORE DEL P.C.I

VISSE IN PRIGIONIA

PER CRIMINALE PERSECUZIONE FASCISTA

FACENDO OLOCAUSTO DELLA

A SERVIZIO DEL POPOLO E DELL’ITALIA

27 APRILE 1937 27 APRILE 1945

HERE

ANTONIO GRAMSCI

LEADER AND FOUNDER OF THE ITALIAN COMMUNIST PARTY

LIVED IN CAPTIVITY

FOR CRIMINAL FASCIST PERSECUTION

MAKING A HOLOCAUST OUT

OF SERVICE TO THE PEOPLE AND ITALY

The surrounding grounds, a parkland full of abandoned olive trees, has fallen into rack and ruin, with overgrown grass and weeds, rotting, upsized paddle boats, and rusty marine equipment. It’s inexplicable how rundown everything is. In other circumstances, it might have been a mini paradise by the sea. Gramsci and Tania would have strolled around this patch sometimes. “I’ve seen some little boys catching fish in the sea,” Gramsci said, in an undated letter to Guilia, one of only a handful written from Formia, “with a hollow brick (filled with air); they filled a small bucket with it.”

The letter is quoted on another plaque commemorating Gramsci, at a park along via Giuseppe Verdi—Parco di Gramsci—a few minutes on foot from the former clinic. The greenspace’s centerpiece is a large marble bust of the man himself, in his younger days, without glasses, looking like a Greek God, dating from April 27, 2000, the 63rd anniversary of Gramsci’s passing. There are two granite writing tablets below, again Greek-style. One says Gramsci was “locked up by the fascist regime, gravely ill, at the Cusumano clinic in Formia, from December 7, 1933 to August 24, 1935,” concluding with the infamous words of the public prosecutor at Gramsci’s mock trial: “For twenty years we must prevent this brain from functioning.”

The adjacent tablet cites his letter about the kids fishing on Formia’s beach, accompanied with words to son Delio, from a 1936 letter: “I think you like history just as I did when I was your age, because it deals with human beings. And everything that deals with people, as many people as possible, all the people in the world as they join together in society and work and struggle and better themselves should please you more than anything else… I embrace you, Papa.”

Gramsci’s Park, alas, resembles Gramsci’s old clinic: jaded and shoddy, falling apart. Maybe it’s just the inclement weather, but everywhere around seems desolate, uncared for, graffiti splattered. The parks furniture and kids’ playground need an overhaul. By all accounts, the site was in an even worse state of disrepair a decade ago. For a while, back then, it was closed for renewal. But the refurbishment hasn’t worn well, and today the park looks a lot like it did in those former days. One image, published in the local newspaper Latina24, from 2014, shows Gramsci’s bust scarily daubed with a swastika, and it reminded me of the desecration of Marx’s Highgate grave in 2019.

It’s hard to know what was being remonstrated here. Was it that local Nazis didn’t like Gramsci? Or was it that the perpetrators thought Gramsci a Nazi? Both are hard to square. Both disturb with their wanton ignorance—though, of course, Nazis aren’t usually known for their smarts. The other thing that disturbs is that the culprits probably hailed from the subaltern classes that Gramsci singles out; someone excluded, unemployed, alienated, having little going on in their lives, with dismal future prospects, and a present full of discontentment. Their resentment prefers lashing out rightward. You’d have thought we’d learned our lesson from the past.

Walking back into town, dampened by the weather and by what I’d seen, feeling a bit dismal myself, I began reflecting on Gramsci’s subaltern social groups, on what it might mean nowadays. A week or so prior to my visiting Formia, I’d read a piece in The New York Times (February 26, 2024), “The Mystery of White Rural Rage,” by Paul Krugman, about rural America, about the baffling political backlash of rural populations. Agricultural employment has declined and small-town manufacturing has all but collapsed. American farms produce five-times more than they did seventy-five years ago with two-thirds less employment. The US has become richer from agriculture, yet rural areas have become a lot poorer. Employment opportunities have dwindled and a loss of dignity around work sets the tone for many rural dwellers, the majority of whom are white.

Anger is voiced against federal government and urban America. Poor city minorities and immigrants have been favored over hard working white Americans, they say, even though federal programs helping poor rural areas—social security, Medicare, and Medicaid—are disproportionately financed by urban areas. Hence there’s actually a de facto net transfer from urban to rural areas. Paul Krugman wonders why, instead of supporting Joe Biden, who has generally been favorable to rural America, bilious rage gives the thumbs up to Donald Trump—“a huckster from Queens, who,” says Krugman, “offers little other than validation of their resentment.”

It’s a curious reinvention of Gramsci’s “southern question.” Only now the southerners in question are those not only geographical southern, but culturally southern, too, people from the periphery who feel that periphery inside them, their own peripheralization from the core, from the north, from urban areas, as if their history is getting overlooked. Occluded in the process are, as Gramsci had it, basic questions of class, of why poor “southerners” don’t identify with poor “northern” folk, yet instead endorse a rich northern real estate fraudster. It’s beguiling. The other point is how subalternity takes on different skin hues—populations who, to greater or lesser degrees, are now marked by outsiderness, by exclusion and neglect, a feeling that their history and culture isn’t acknowledged by the perceived powers that be.

Gramsci’s southern question essay hoped for a Left turn in southern sensibility. Yet current climes suggests otherwise, that certain subalterns value more the visceral bleat of the Right. Krugman reckons white rural rage “is arguably the single greatest threat facing American democracy,” and laments, “I’ve no good ideas about how to fight it.” Meantime, white rural working classes give gung-ho support to politicians who tell them the lies they seemingly want to hear. Gramsci knew about baffling reactionary politics, about how, sometimes, many subalterns end up voting for politicians and programs that go against their better interests. He tried to tell people the truth and got locked up for it.

Marxists once used to talk about “false consciousness,” the obverse of “knowing thyself.” For decades, false consciousness went out of fashion, yet lately it’s well and truly back in vogue, assuming an almost objective status, blurring reality and make-believe, so entrenched has it become in our society, so ubiquitous in our mass and social media, so commonplace in the misinformation sprouted by our politicians. All of it conspires to convey an implicitly distorted sense of reality, handy for vested political and economic interests—like it always did. A form of widespread brainwashing, where it’s easier to be believed for peddling lies than for telling the honest truth.

Gramsci emphasized the need for intellectuals to correct misconception, to persist in telling the truth, to go and voice it to the people. But maybe intellectuals have turned away from the people, just as the people have turned away from intellectuals. Maybe we’ve let the people down, retreated to our college campuses, given ourselves over to management committees and research assessments. We’ve been busier raising money rather than raising a ruckus. We’ve been bought off by the good life or else gotten complacent.

Or maybe a lot of us have simply gotten depressed about a Left always being in “a state of anxious defense,” forever on the backfoot, or more often entirely lame, and we’re happier sitting behind our desks writing stuff like this. Organic intellectuals have gone elsewhere for nourishment, turned traditional. Or perhaps the most effective “permanent persuaders” have been those on the right-flank, relentlessly inveigling people that lying is the winning ticket, that crank demagogues will really make things great again.

Notwithstanding, Gramsci continues to inspire, come what may. He inspires me, at least, and the countless people I’ve seen coming to the cemetery to pay their respects. He especially inspires in these dire circumstances because he was a Marxist who’d made dire circumstances something of a specialty. The idea that things might get better, that people matter, that not everybody is innately bad or a fool, that the truth will prevail in the end, is something he never ceased to endorse. It’s a belief-system that comes without guarantees, and often Gramsci made statements that were positive but then tinged them with doubts and caveats, with criticisms of criticisms. “Everything that deals with people,” we can remember him telling his son, “as many people as possible, all the people in the world as they join together in society and work and struggle and better themselves should please you more than anything else. But is it like that?”

I really hope it is…

Dear Andy,

Another fine essay on Gramsci. This definitely has to be made into a book at some point. We published (in 2009) an English translation of Antonio Santucci’s book on Gramsci. Joseph Buttigieg wrote a Nota for the book, and he and I had some correspondence so I could get this in English. Hard to believe he is the father of the current US Secretary of Transportation. Oh well, Kamala Harris’s dad was a radical too.

Gramsci is a person after my own heart. I tried to be something of an organic intellectual, by teaching working-class people, for example. It was remarkable how few others cared to do this kind of work. Krugman’s remarks on rural America are partly true, but naturally he has no idea what to do about this. But even the labor unions have abandoned the abandoned, in the dead industrial towns of the Midwest. In my hometown, where nearly everyone was in the working class, Trump reigns supreme. The factories closed, drugs took over, and hope is hard to find. In these places, where often there are few if any immigrants, people go on and on about the immigrant hordes ruining the nation. As for rural areas, they have been abandoned. What really has Biden done for them? Nothing. Yet, a person I know is busy in Iowa promoting, with some success, organic farming. And given that rural areas used to have a strong sense of mutual aid, it is ridiculous to think that this could not be revived. The left thinks of these places as “flyover” areas, to be avoided at all costs. Maybe they are hopeless, but nothing good will come of a left that thinks it is changing the world one conference at a time! It would be good if young people turned to the land and went there to try and build new communities. As I write these words, I think maybe I am going crazy to have such thoughts. But there are a couple billion peasants still in the world. They could revitalize agriculture not just where they are but in the places they are often forced to go. I wonder if people in rural areas couldn’t be convinced by a popular movement to embrace these people, welcome them to the land and work with them to make rural places vital once again.

Just some random and probably foolish thoughts. Inspired by what you have written and by what Gramsci said.

Take care, my friend,

Michael

ps How can the rural poor be the greatest threat to democracy? What about the billionaires and mega church leaders working day and night to create a rural poor as ignorant as can be imagined. Samoza once said he didn’t want thinking humans. He wanted oxen. True for all of our libertarian billionaires. They really are fascists.

LikeLike

Pingback: Andy Merrifield, ‘The Subaltern in Gramsci’ | Progressive Geographies