Some days, the music seems over for Main Street GB, for the great British High Street. And when the music’s over, in the immortal words of The Doors, “turn off the lights.” British High Streets have had their lights turned off long ago. We’ve canceled our subscription to the resurrection. Few joyous sounds are heard. A stroll down the local High Street isn’t so much a jaunt along Easy Street as a plunge into “Hard Times,” something Dickensian, full of bleak houses. Indeed, COVID sealed the already-precarious fate of High Street commerce. Long-range entropy turned into sudden catastrophe.

Store closures, bordered up premises, dreary, disheveled streets, with dreary, disheveled people, worn down by life’s hardships, strike as the order of the day. Under a typically gray British sky, everything becomes even more depressing, if that’s possible. Those businesses still in business, like the ubiquitous array of High Street chains—Boots, W. H. Smiths (surely the dreariest store in the land), Superdrug, etc., etc.—hardly raise one’s spirits. They’re about as inspiring as a stick of celery in a lonely field.

Well before COVID, the British High Street was on the rocks. Yet after successive lockdowns, estimates reckon 11,000 stores have gone under, tipping a lot of High Street retailing over the edge. Unit vacancies currently stand at around 16 percent. The bulk of the casualties are chain outlets, unsurprising given that for decades chains have colonized our High Streets everywhere. They’ve monopolized and driven out smaller businesses. They’ve been pretty much all the High Street commerce we’ve had. But in killing off the competition, they overextended; and now, overextended, they’re downsizing, leaving people with no alternative. Save thrift (charity) stores. Up to 18,000 more stores, restaurants, and leisure outlets could fold as major retail groups like Debenhams, Topshop, and Dorothy Perkins collapse. Meanwhile, Marks & Spencer, with reported losses for 2020/1 of over £200 million, have axed over 100 of its stores nationwide; more closures are imminent.

House of Fraser (owners of Debenhams and Topshop) have also shut over 100 stores, including their London flagship at the iconic art deco building on Britain’s prime High Street, Oxford Street. Billionaire Mike Ashley’s Sports Direct bought House of Fraser in 2018 but has struggled ever since. According to one business commentator, “House of Fraser stores are drab, staff levels are low, and service terrible.” It’s pretty damning. Stores have failed to adapt to consumer demands, critics say, for both an in-house and online consumer experience. And now they’re paying the price (“What Does the Closure of House of Fraser’s London Flagship Mean for the UK High Street?” Retail Gazette, November 23, 2021).

Retail analysts reckon further troubles are in store for the British High Street. The challenge is how to reinvent it, how to make High Streets and city centers less reliant on chain retailing, maybe even less reliant on retailing tout court. In the meantime, the predictable and boring High Street we once knew is soon destined to become a whole lot worse: deserted, boarded-up, jobless. For decades, we’ve been in a grip of a Hobson’s choice, between a sterile wilderness, on the one hand, or a dead wilderness, on the other. Alternatives have been throttled by market forces, by a lack of imagination and political will. Identikit Britain needs a new value system for its cities and towns.

***

Growing up in Liverpool in the 1970s, I remember a time when you couldn’t get a decent cup of coffee anywhere on the High Street. This was very troubling for me, a wannabe French surrealist shacked up in gloomy Garston. Those surrealists used to drink a lot of coffee. They liked to talk and hang out in cafes. And with all that caffeine inside them, afterward they liked to walk the city streets. In those streets, they said, you could discover novelty and chance encounter. That’s the meaning of life in the city, they said, novelty.

A bit later, I read Jane Jacobs. Jacobs drank more gin than coffee. She particularly liked her local—New York’s “White Horse Tavern,” along the same Greenwich Village Hudson Street block she lived. Jacobs didn’t much like what planners had done to cities both sides of the Atlantic, nor what they were to mastermind. They peddled the silly idea that functional separation was the way forward, that spaces should have mono-uses—work here, residence there, leisure someplace else. Jacobs said this destroyed the mixed land uses and diversity that made neighborhoods vibrant, that brought life to cities of all shapes and sizes.

Decades on, weird things happened to our cities. Since Margaret Thatcher, we’ve not had much planning, even of the sort Jacobs dissed. The “free” market has decided things. And the free market soon discovered coffee. We have more places nowadays to drink coffee than the surrealist could ever have imagined. We know something’s up when Whitbread, the brewery group, started shutting its High Street pubs and diversified into coffee, supplying us with a Costa Coffee on every street corner—or on every other street corner, next to every Co-op, with a Starbucks and Caffè Nero close by. The surrealists can get their caffeine rush. But where, after supping, would they wander, seek out that novelty and fleeting delight?

Once the famine, lately the feast, an orgy of sameness. Steadily but surely, up and down the country, in that free market economy, our big cities and little towns have become alike. Predictable chain stores dominate, too ubiquitous to mention. When Whitbread acquired Costa in 1995 for £19 million, it had 39 stores. When Whitbread went on to sell Costa to Coca-Cola in 2018 for £3.9 billion, there were thousands of stores—in fact, 2,700 as of 2021. Since the pandemic, though, Costa-Cola has slashed 1,650 jobs, amid store closings and staffing purges nationwide—including 40-odd closures on mainland China. (I remember a few years ago flying to Australia, waving goodbye to a Costa at my Heathrow gate, only to be greeted by another Costa hours later, stepping off the plane at Dubai.)

Maybe it’s just me, but there’s something about the taste of chain store coffee; Costa’s, like all the rest of them, has a sharp metallic bitterness about it, only ever tasting one way, irrespective of the store, irrespective of who makes it. Little wonder most people want to drown that bitterness with masses of milk and sugar, or with frothy cream and chocolate and Lord knows what else. Personally, I like to think coffee drinkers might opt for a less reassuring sterility of taste and place if they were given the choice. Perhaps it’s too late. Perhaps they’ve already been conditioned into knowing only that taste. Which, of course, was the chains’ principal objective in the first place.

I’m old enough to blame it on Thatcherism. Planning was bad, but no planning is worse. Though let’s be clear: it’s not like there hasn’t been any planning; more that our local authority planners have been bought off by those same big chains. They’ve had their pockets lined and political ambitions anointed. They’ve granted planning permission where they shouldn’t have, given it for anything and to anybody who’ll bring commerce to town, kowtowing to big chains most of all, offering them the kinds of tax breaks and rent holidays they’d never dare offer struggling independents.

Our local politicians and planners believe big chains are the most economic reliant, the most economically resilient. Famous last words. It’s a warped understanding of monopolistic economics, and of what a rich urban culture should be all about. Meanwhile, honest planners haven’t been very imaginative, or have given up too depressed. They should’ve read more French surrealism. And more Jane Jacobs. Nor has the free market been very free. Our cities are arenas for high yields only, for gleaning land rent, for making property pay any way it can. People are priced off the land. Only rich companies can afford to stay put. And then they leave.

***

Surrealism has been on my mind penning these words because I’ve just visited a big exhibition at London’s Tate Modern gallery: “Surrealism Beyond Borders.” Many years ago, I swore I’d never go to another museum to see another Surrealist exhibit. I’d seen hundreds. They’d usually been curated pretentiously, smacking of pomposity and self-importance. They never captured the surrealism that I carried around in my head. Catalogues, compiled by art critics, invariably stressed fantastical juxtapositions and counter-hegemonic practices, liberational assemblages and strategies of defamiliarization—academic jargon destined for Private Eye’s “Pseud’s Corner.” Usually, too, these exhibitions of artworks by artists that hated conformism and predictability were colossally conformist and predictable, and such was the Tate’s. Still, inexplicably, I went, somewhat predictably.

The exhibit, initially unveiled at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in late 2021, was vast, spanning eleven large rooms of the Bankside gallery, with paintings, drawings, photos, pamphlets, and films of surrealisms from around the globe, beyond a Paris-centric identity: from Osaka and Bogota, Mexico City and Cairo, Haiti and Havana, Mozambique and Korea. Points of transnational convergence were highlighted, shared political allegiances; shared fears, too, about the state of world, about colonialism and war, about exile and authoritarianism, about civil rights and the plight of the creative artist in repressive societies. Those concerns never seem to die out entirely.

The collection was also keen to place greater emphasis on surrealist women artists, like Leonora Carrington, Kati Horna, Frida Kahlo, Françoise Sullivan, Dorothea Tanning, and Remedios Varo; and on non-white males, like the voodoo-Afro-Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (with a Chinese father), and the American trumpeter, poet, painter, and black power activist Ted Joans, whose “Long Distance” exquisite corpse drawing game, produced over 30 years and pasted together from 132 collaborators on three continents, concertinas to over 35 feet in length, unfolding as almost the backbone of the whole exhibition. “Jazz is my religion,” said Joans, “and surrealism my point of view.”

While much of “Surrealism Beyond Borders” left me cold, typically dissatisfied, walking out the door, I knew, like other Surrealist exhibitions I’d seen, it didn’t leave me with nothing: I’d had an encounter of sorts, getting me daydreaming about something. Besides all else, it made me think that those surrealist painters, photographers, and writers had much more interesting lives than ours, more experimental, more tumultuous lives; and they lived in more interesting places, more alive cities. I still dream of a piece of their action. But changing our way of seeing cities is more vital now than what changes our way of seeing a painting in an art gallery. The surrealists tried to make art-form a life-form. They drew on dreams and desire in conscious life. They wanted each to mutually inspire, to conspire as a new reality. The unconscious and conscious were to come together somehow, to encounter one another, to find a home in the city.

Encounter here meant more than mere meeting or rendezvous, more than a simple get-together; a complex get-together, perhaps, an interesting encounter, a contradictory, even conflictual encounter, an encounter that stimulates, that enlivens the senses, that teaches. That’s what cities ought to be, surrealists said: sites of encounter, sites of “superior events,” as Breton put it. That’s how urban dwellers could prosper, could feel more alive, be less bludgeoned by drudgery. Surrealists wanted people to inhabit a landscape of dream and desire, and Surrealism built this dream house in the ashes of the dominant order, out of disgust and distrust of this order; and so should we.

Surrealism rings out like a public payphone waiting to be randomly picked up. Its call needs to be answered, its message passed around; its sound needs to resound, to echo beyond the museum walls. It needs to drift into the streets, out onto the High Street, where it’s really meant to be. Surrealism needs to find a voice again, become a soundscape, like a Ted Joans poem, played to jazz, to Monk, or to an Archie Shepp horn. At the Tate, one of the few highlights for me was watching Joans in action, reading aloud to Shepp’s tenor sax, in William Klein’s film of the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers. Shepp, a self-avowed communist (as well as poet and playwright), idolized Charlie Parker before finding his own innovative voice in the early 1960s playing with the legendary avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor. If only our cities could resemble in form and content the lyrical atonal notes of tracks like “Lazy Afternoon.”

The surrealists were wont to shock and exaggerate and André Breton particularly like to invoke Lautréamont’s exaggerated verse to shock most. Breton loved Lautréamont’s Maldoror (1869), a poetic flight of fancy, the epic odyssey of Maldoror, “the prince of darkness,” whose bizarre hallucinations became Surrealist touchstones: “the fortuitous encounter on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” Refrains like these, intending to provoke outrage, reveled in encounters between absurd things that were very hard for ordinary folk to get their heads’ round. Yet the message was brought to earth later by Thomas Pynchon, himself no stranger to the genre. Pynchon said he’d discovered Surrealism in the 1950s and took for it “the simple idea that you could combine inside the same frame elements not normally found together to produce illogical and startling effects…but any old combinations of details will not do.”

But the contrasts between the ideals of “Surrealism Beyond Borders” and the London cityscape are stark; and it’s impossible to get that contrast inside the same frame. Exiting the Tate Modern that day, I crossed over the Thames on Norman Foster’s Millennium Bridge (co-designed by sculptor Anthony Caro), intent on a Surrealist dérive around central London. (On opening day, in June 2000, Londoners nicknamed this structure the “Wobbly Bridge,” as the slender ribbon of steel swayed alarmingly in the cross breeze blowing off the river.) Directly ahead is St. Paul’s Cathedral. Passing along St. Paul’s Churchyard, I’m headed west on Ludgate Hill. Already those chains are in abundance. There’s Côte Brasserie (higher end faux French restaurant chain), Sports Direct, McDonald’s (practically facing St. Paul’s), and Wagamama (fusion Asian food chain). Walking along, I’m greeted by Costa Coffee, Greggs (the dreadful British bakery chain, with 2,000 outlets nationwide), and Pret à Manger.

Ludgate Hill is lined with “TO LET” signs both sides of the street, flagging the ubiquity of office and retail vacancies. As I approach Farringdon Street, Leon (fast food chain) is on the corner, near Holland & Barrett (vitamin, nutrition supplement and health food chain). Over Farringdon Street, there’s Marks & Spencer, more empty stores with “TO LET” signs, Boots, Sainsbury’s Local, and then KFC. It’s a motley array of sameness. No matter where you go, whether you’re in central London or central Bury, these chain outlets are all absolutely the same everywhere: same store furniture, same colours, same layout, same menus, same décor, same shelf stock, same staff uniform, same smell, same feel, same same.

Turning right up Fetter Lane and another Holland & Barrett, with Pizza Express opposite. For a while, retailing disappears. Few people are about. The street is desolate. Fetter Lane becomes New Fetter Lane with office space on each side of the street, many new, sleek glass buildings. Their height, while medium rise, is too tall for the narrowness of the street, so everything feels enclosed. The space is dead. Defoe would have walked these same streets, as would his sympathetic, eccentric flâneur, H.F., as would Moll Flanders (Newgate Prison, after all, is just around the corner). Plague notwithstanding, these streets would have been more bustling then, more intensely alive, densely populated by people and dwellings, neighborhoods not yet emptied out by office space—by now-redundant office space. These streets were coffined even when their offices were alive with occupants.

Now, there’s around 58 million sq. ft. of empty office space in London. Commercial property specialists suggest that with flexible work trends and remote working—the future long-term trend for around half of the UK’s workforce—unused commercial office space will continue to grow. Few businesses now want to commit to long-term leases; over 60 percent of the office space providers offer reduced rates or rent holidays. As of March 2022, weekly London office occupancy was 31 percent, compared with 63 percent pre-pandemic. Lights on, nobody at home. Soon, too, these lights will turn off. (Even so, with the prevalence of cranes in the City of London, offices are plainly still getting built, and still, unbelievably, gaining planning approval.)

It’s hard for pedestrians not to feel the disconnect here, the way Jean-Paul Sartre’s protagonist Roquentin felt it in Nausea: a human being encountering cold inanimate objects, objects everywhere around you, that tower over you, that provide the context of your life—objects you must live with yet are somehow cut off from you, beyond you, against you. They make you shudder with that feeling, with the nausea that overcomes you, that alienated subjectivity. It’s the landscape of money and finance, of High Street chains that enchain, that flatten life, that reduce much that surrounds us to a passive one-dimensionality. It brings on nausea. Or, rather, as Roquentin mused, “it is the Nausea. The Nausea isn’t inside me,” he said. “It is everywhere around me…It is I who am inside it.”

New Fetter Lane opens out onto High Holborn, and I turn left headed west, passing Wasabi (sushi chain), over Gray’s Inn Road, encountering more office buildings, then Caffè Nero, another Greggs, and a (public) street sign with a McDonald’s “M” on it, attached to a lamppost, giving directions to the said hamburger joint. Then Dorothy Perkins, Superdrug, another Boots, and another Leon; soon another McDonald’s sign, similarly positioned on the public byway (how do they get away with it? Maybe because there’s no mention of McDonald’s by name, nor any image of their food), Blackwell’s (chain bookstore), and another Pret à Manger. I cross the bottom of Red Lion Street, passing another Pizza Express, just before Procter Street, I’m greeted by another Pret à Manger, hardly 400 yards from the previous one. Crossing Procter Street there’s another Superdrug, another Caffè Nero, New Look (clothes chain) and another Costa Coffee on the corner of Kingsway, next to Holborn Tube Station, with another Wasabi on the other side of the street.

Over Kingsway comes another Sainsbury’s Local and another sign for McDonald’s. I decide to walk up Southampton Row, headed north now, passing a batch of vacant stores, looking like they’ve been vacant since well before the pandemic. There’s a lot of litter swirling about and the landscape is worn and forlorn. I cross over Vernon Place, with another Sainsbury’s Local to my left, and another Holland & Barratt to my right, then Ryman (stationary chain). Soon Taco Bell, facing which is another Costa Coffee, and McDonald’s. Russell Square appears immediately to my left and after a little while I turn right onto Bernard Street, encountering another Pret à Manger and Tesco Express, before joining the south end of Marchmont Street, opposite Russell Square Tube Station.

Now, in the heart of Bloomsbury, for the first time on a foot journey nearing 3 miles, things get more interesting. I head up Marchmont Street, with the Brunswick Centre on the right (a concrete, high-density, modernist housing structure, built between 1965—73), and the Marquis Cornwallis pub appearing to my left. Just afterward comes Marchmont Street’s Post Office, lined outside by a large fruit and vegetable stall, my first glimpse of anything fresh. Immediately following it also my first glimpse of anything independent: “Bloomsbury Building Supplier,” a locally owned hardware store and paint and plumbing supplier. It’s been around here for thirty years, probably more. I know this because, in the mid-1990s, I used to live around the corner, on Coram Street, and the hardware store was already well established then, frequented by me included. Not far away, on the other side of the street, is Alara Health Food and Organic café, another independent and longstanding feature of the block. Ditto “Gay’s the Word,” an independent LGBT bookstore, set up by a group of gay socialists in 1979, still miraculously hanging on.

There are other wonderful independent bookstores along Marchmont Street: SKOOB and Judd books, the latter being one of my all-time favs, dear to my heart when this was my neighborhood. It’s still run by the same two guys, now a lot grayer. SKOOB, nestled in the Brunswick Centre, 50 yards off Marchmont Street, is a more recent arrival. I remember it years ago at Sicilian Avenue, off Kingsway; and Judd Books was called “Judd Street Books 2” then, since the original Judd Street books was on nearby Judd Street, a little farther north, just south of King’s Cross Station. That location always felt peripheral to me; the owners agreed, eventually amalgamating their stock in the Marchmont Street premises, retaining the Judd Street name but later dropping “Street.”

Marchmont Street was the London street I loved best. It was where I wanted to live, on it or nearby. It didn’t only have bookstores and cafés; it also had an arts cinema, “The Renoir,” still has it, in the Brunswick Centre, a stone’s throw from my apartment. The neighborhood was my little utopia for a while. If anything, the changes taking place there over past decades, rather amazingly, have probably been for the better. The street hasn’t lost its charm. Independents have been able to flourish, despite rising rents. This is a segment of London I know intimately, and it was always the intended terminus of my walk across town. I confess it, like the philosopher Louis Althusser “confessed” about his “reading” of Marx’s Capital, his “guilty” reading. He was no innocent reader, and neither am I, similarly reading central London’s landscape with intent, like Althusser read Marx’s landscape in Capital, unpacking meaning, probing absences and presences, sights and oversights, the visible and the invisible. I could never be an innocent flâneur, a casual stroller through town, mimicking the casual reader strolling through a text. Instead, there’s too much interrogation going on, too much critical investigation, so I confess my crime, my guilty reading, my partial eying of the cityscape around me.

Marchmont Street, for me, was the nearest thing in the UK that resembled anything Jane Jacobs evoked in Death and Life of Great American Cities. Here, I thought, were some of the inspiring qualities of her “intricate street ballet,” ebbing and flowing in its “morning rituals,” in its “heart-of-the-day” and “deep night” ballets. Marchmont Street likewise exhibited mixed-use diversity and clientele—young and old, students and bohemians, Asian kids and families, tourists and locals, yuppie professionals and poorer working classes, blacks and whites, gays and straights—out in public in a central London street. A real rarity. A community center, a hardware store, a launderette, a dry cleaner, a post office, a bakery, a dentist, a newsagent, three hairdressers, a health food store, a Halal food store, two pubs, a betting shop, several cafes (independents as well as a Costa), three bookstores, a Waitrose supermarket (nearby in the Brunswick Centre), a cinema, together with Chinese, French and Indian restaurants, all relatively happily share the space of one small neighborhood block.

In bygone days, a café called Valencia served as my surrogate living room. It’s still around today, though with a bit of garish makeover since my residency. I used to sit there for hours, up on a stool overlooking a window, drinking coffee, losing myself, trying to find myself, all the while watching the world go by outside. Inside, I felt a part of this outside action; detached from it, anonymous, sufficiently absent, yet absolutely present. I surveyed the crossroads, the junction with Tavistock Place, monitoring things to the west and east, everything to the north; and, turning around, I could glimpse stuff to the south as well. I could see all, from this panoptic patch on planet earth. Sometimes, while I sat, I thought I didn’t have to go out into the world anymore, because, here, the world sort of came to me. I’d sip cappuccino, stare out the window, listen to the radio, feel the pulse of neighborhood life going about its daily round. I spent so much time there that its owners—two Egyptian brothers—used to give me a present every Christmas.

Those café days along Marchmont street convinced me that the Surrealists and Jane Jacobs knew what they were talking about when they talked about cities. One feature Jacobs insisted upon was that cities need hearts. If we open our ears, we can hear that heart beating, a human sound, like music. There’s a natural anatomy to urban hearts. Big cities usually have more than one heart, just like they have more than one High Street, one Main Street. Yet always these hearts will beat at busy pedestrian intersections. “Wherever they develop spontaneously,” Jacobs said, hearts “are almost invariably consequences of two or more intersecting streets, well used by pedestrians.” They’ll have corner stores or corner cafés, corner pubs or corner public squares. Hearts thrive off diversity not homogeneity. Rich people and rich businesses see city hearts as profitable financial investments, as organs to pump up and artificially inseminate. Under their watch, cities might look pregnant with possibility. But their real hearts have become sclerotic.

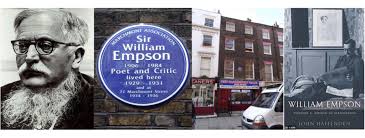

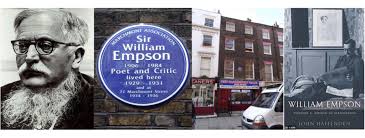

Nevertheless, on odd occasions, by some minor miracle or another, streets like Marchmont Street cling on to life, continue to have beating hearts. They retain diversity, manage to hold on to street spontaneity, to a certain kind of urban ambiguity. Things that shouldn’t co-exist do co-exist. Perhaps it’s no irony that one of our prophets of ambiguity, the poet and literary critic William Empson (1906-1984), twice opted to live along Marchmont Street; once between 1929-1931, and again between 1934-1936, at number 65, in a second-floor apartment now commemorated by a blue memorial plaque. Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity, published in 1930 at the tender 24-year-old—precociously begun as a Cambridge University undergraduate–became a landmark in poetry criticism and was likely fine-tuned and finished off at his Marchmont Street abode.

Whether deliberate or subconscious, Empson said that the best poetry makes the best and subtlest uses of ambiguity. So should the best and subtlest urban planning and design. Maybe, then, we can conceive Empson’s critical and creative treatise about poetry as a manifesto about the form and functioning of our cities. At its best, the city is a sort of poetic text, with the same rhymes and rhythms, same ambivalences and ambiguities as those of the best literary refrains.

Whether deliberate or subconscious, Empson said that the best poetry makes the best and subtlest uses of ambiguity. So should the best and subtlest urban planning and design. Maybe, then, we can conceive Empson’s critical and creative treatise about poetry as a manifesto about the form and functioning of our cities. At its best, the city is a sort of poetic text, with the same rhymes and rhythms, same ambivalences and ambiguities as those of the best literary refrains.

For many people, city life is ambiguity, a constant struggle between the realm of necessity and the realm of freedom, a balancing act between working and living, an active tension and perpetual contradiction. Marx himself devoted much attention to this ambiguity, to how the two collided in the socialist imagination, and how the Good Life involves liberation as well as livelihood. In Volume Three of Capital, he says the realm of freedom begins only where the “mundane considerations” of necessity cease. Freedom begins, in other words, when basic needs for food and shelter are satisfied. A shortening of the working day, he says, is a prerequisite for making people freer and happier, for enabling ordinary folk to undertake more edifying activities that the world of work usually denies.

All kinds of aesthetic and creative endeavors might thereafter be released, even if it’s just having more time to paste postage stamps in an album or chase butterflies in a field (which Breton loved to do at his home in St.Cirq Lapopie). Thus, sensual stimulation—pleasure, adventure, experiential novelty—is also a basic human need, Marx thinks, even though it’s a category invariably commandeered by the idle rich, by the independently wealthy. Marx, however, insists that sensual stimulation is a right for everyone, not just for an entitled minority, who buy or inherit their privileges, who monopolize them at the expense of everybody else.

Marx always held this ambiguity between freedom and necessity in creative tension. He seemed forever torn between a workerist, Promethean vision of life, and an Orphean passion for play and pleasure. He tended to favor the former later in life and the latter in his youth. He knew, needless to say, that the two realms needed conjoining, that ethics and aesthetics had to co-exist. Yet he never quite figured out how to conjoin the two Marxes in his Marxism. Maybe for good reason: not only did he say he wasn’t a Marxist, but he equally rejected utopian thought because it tended to favor one over the other: either a dour, closed, anti-human system or a self-realization based on “mere fun” and “mere amusement.”

That said, Marx never positioned himself in the center, never chose compromise. Instead, he challenges us to imagine critical and radical forms of an Open Society, a society where people might work (necessarily, without surplus time) and be free, feel at once whole and more alive. He roots for a social and physical environment where the possibilities for human passion might heighten; where our senses—seeing, feeling, hearing, smelling, tasting, desiring, and loving (all Marx’s words)—blossom as “organs of individuality” and “theoreticians in their immediate praxis.”

Here the city comes into its own as a life-form and life-force, as a normative social space, where civic and cultural spaces, High Streets and backstreets exist to promote and give scope to intense human experience and diverse human activity. In them, people might inhabit and participate in a more wholesome reality, a bit like a busy local farmers’ market, where, al fresco, crowds congregate expectantly and the countryside encounters the city in all its ambivalence, like the fruit and veg being sold: misshapen, frequently dirty and battered, yet invariably flavorful and of high-quality. Products are unalienated, just as direct engagement with producers is unalienated, just as the space itself expresses an honest clarity. Above all, everything tastes, and in our contemporary processed age that’s saying plenty. Items on sale are the kind of products dumped by big chain supermarkets, whose stock are perfectly formed, mass-grown specimens, utterly devoid of dirt and flavor, like big chain cities.

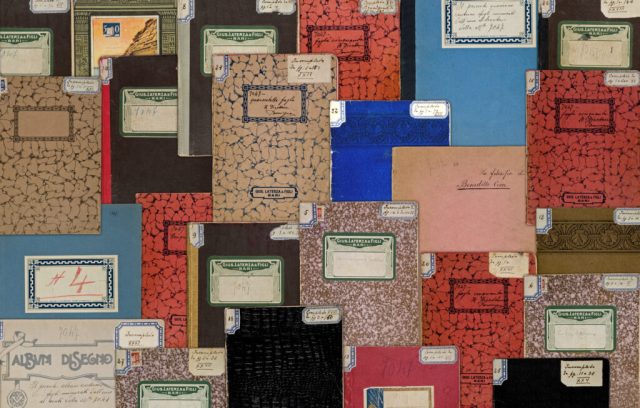

A farmers’ market isn’t, of course, the only possible paradigm for wholesome urban space. Maybe another is the flea-market, something cherished by the Surrealists, especially by André Breton. Remember, early in Nadja, Breton wandering around Paris’s great open-air marché aux puces at Saint-Ouen? He loved doing it every Sunday afternoon, he said, best of all with a friend. A little beyond what’s now the Boulevard Périphérique, not far from the Porte de Clignancourt, Saint-Ouen’s flea-market has been around since the early 1870s, when ragpickers, clochards, and bric-à-brac dealers, deemed insalubrious by the bourgeois powers-that-be, were evicted from central Paris.

They soon installed themselves and their makeshift street bazaar in the northern periphery’s no-man’s-land zone and have been there ever since. The flea-market thrived as a venue where Parisians could hunt down trouvailles, find antique oddities, upscale garbage, arcane wares (fossils, taxidermy, rusty old mechanical devices, etc.), as well as the occasional period treasure and artistic masterpiece—all at a price you could haggle over. For the surrealists, Saint-Ouen epitomized a site of the chance encounter, with objects and people; surprises lurked around every corner and under each pile of junk. The surrealists would unearth here the artistic throwaways and ready-mades they’d make legendary.

In Nadja, Breton describes how, one Sunday, he and Marcel Noll visit Saint-Ouen. “I go there often,” says Breton, “searching for objects that can be found nowhere else: old-fashioned, broken, useless, almost incomprehensible, really perverse objects in the sense I mean and love.” At bazaars like Saint-Ouen, Breton says he delivers himself to chance, revels in circumstances “temporarily escaping my control,” gaining entry “to an almost forbidden world of sudden parallels, petrifying coincidences, and reflexes peculiar to each individual, of harmonies struck as though on the piano, flashes of light that would make you see, really see.” Breton was a man who once gave one of life’s great directives: “Expect all good to come from an urge to wander out ready to meet anything.” In a beguiling passage in Nadja, he says “I almost invariably go without specific purpose, without anything to induce me but this obscure clue: namely that it (?) will happen here.” (The point of interrogation is Breton’s own. What is the “it” in question? Who knows? Can anybody know? That’s Breton’s point.)

Several years later, in Mad Love, he recounts another trip to Saint-Ouen, this time with sculptor Alberto Giacometti, on “a lovely spring day in 1934.” “This repetition of the setting,” he qualifies,” alluding to Nadja, “is excused by the constant and deep transformation of the place.” There’s enough novelty going on, Breton hints, that you’ll never exhaust your visits, never walk through the same waters twice. Saint-Ouen is constantly changing, is the source of constant change, even to this day, and always there’ll be “the intoxicating atmosphere of chance.” “It is to the recreation of this particular state of mind,” he puts it in Mad Love, in Giacometti’s company, “that surrealism has always aspired.” “Still today,” says Breton, “I am only counting on what comes of my own openness, my eagerness to wander in search of everything, which, I am confident, keeps me in mysterious communication with other open beings, as if we were suddenly called to assemble.” “Independent of what happens, or doesn’t happen, it’s the expectation that is magnificent.”

In these passages, Breton touches on some of the grand themes of the Surrealist movement: an openness to novelty and chance; a celebration of adventure, of plunging into the unknown, somewhere unforeseen, impossible to anticipate in advance, someplace where an encounter happens—an “it,” as he calls it. Meanwhile, the expectation of finding something, some new novelty or discovery, some trouvaille, is just as important as actually finding it, as actually realizing the expectation. And, finally, for Breton, such above traits are distinctively human traits, putting us in “mysterious communication” with one another. We need this mysterious communication somehow, and we’re prepared to assemble around it. There’s a generosity of spirit here, and one question we might ask ourselves now is: are we already picking up that ringing surrealist public payphone?

It probably sounds bizarre but maybe the thrift (charity) stores we’ve seen burgeon up and down the land, even before COVID, are the closest things we might encounter to the surrealist flea-market. Don’t they touch on the same sort of serendipitous experience? As businesses fold on the High Street—failed independents, runaway chains—thrift stores have moved in, occupying empty units, becoming a ubiquitous presence everywhere; a predictable external sight, perhaps, yet an internal adventure for everyone who crosses their threshold. Some people hate thrift stores: they smell musty, of body odor, and they’re full of trash, and you never know who’s worn those clothes. Others, seemingly the majority of people, love them. Maybe because of our deep-down yearning for novelty, maybe it’s that which is borne out in thrift stores? The human need for experiencing the unexpected? You’re not sure what you might find in each visit, what shirt or blouse or jacket lurks on the rack, what record or DVD or used book, what household ware or piece of furniture; and at what price, something cheap, something designer, something you never thought you wanted and had no intention of ever going out to buy. And even if you find nothing, you’ve been stimulated, were expectant.

Indeed, you enter each store with a sense of expectation. A bit of adventure to the usual everyday mundanity. Of wanting to dig around stacks that don’t resemble anything you’d find in a chain store. You already know what you might find there, in an environment that’s anodyne and sterile, uniform and highly organized, programmed; that offers no real choice with its rows and rows of stuff, piled high. No serendipity, no novelty, no surprise. Nothing is left to chance. The atmosphere is oppressive, the staff alienated. Not so with the thrift store. A welcome antidote to the predictability and sterility of the High Street. A relief to pass time in a more friendly, relaxed, and informal ambience, where people freely chose to be in, to work in. Besides, isn’t it a good thing for the environment that those items are getting recycled, that there’s less waste? And because thrift stores are registered charities, aren’t they generally supporting a good non-profit cause, as are the people who shop there? Worlds removed from businesses answerable to shareholder greed.

But thrift stores are ambiguous, too. If they didn’t exist, there’d be gaping holes along the High Street. Isn’t that good? Yes and no. There are more than 10,000 thrift stores in the UK; others seem to sprout every day, almost overnight. Charities receive mandatory 80 percent relief on business rates if their premises are “wholly and mainly” used for charitable purposes. In many instances, local authorities, keen to keep footfall on the High Street, desperate to fill vacant units, have topped up this relief to 100 percent, basically meaning big, rich multinational charities like Oxfam are exempt from paying business rates. The little entrepreneur who wants to start up her café business in the empty spot next door won’t get off as lightly, will be compelled to pay the market rent as well as the going business rate. That way, the proliferation of charities along the High Street guarantees market rents will never go down, even with an over-supply of retail rentals. Charities effectively mask capitalist failure without ever resolving the causes of this failure. And unlike an independent business, who pay salaries to any employee, charities benefit from volunteer labor. They thus offer novelty on the High Street without ever offering paid work on the High Street.

Yet maybe the future of the High Street isn’t about paid work anyway. Nor about conventional retailing, conditioned by the laws of exchange-value. Maybe it’s more about entertainment and leisure, about use-value, novelty, and human encounter rather than strict monetary, financial encounter. Since COVID, some local authorities have balked at offering full rate relief to charities. There have been other appeals, too, to abolish rate relief entirely, to get charities to cough up fully on business rates; it’s a rebate that’s effectively worth around £2 billion each year. (Even if the rate were only 50 percent, £1 billion might accrue for other uses, be put into a national fund that could support regional small businesses, especially in distressed areas.) Is there another urban strategy that might nurture thrifts alongside independent activities, like artisanal pop-up stores, temporary art galleries, and attic sale activities?

Can’t the High Street be pedestrianized on certain days and hours to encourage more regular street markets and farmers’ markets, pop-up events, and street dining. The pedestrianization of Soho, which shuts off its 17 streets to vehicles between 5pm and 11pm to accommodate outdoor dining, offers a remarkable vision of a “hospitality recovery plan” (as Westminster City Council calls it). Sitting on chairs around tables from adjacent restaurants and cafés, Soho streets bustle with people. An amendment to dining laws, announced this year in the Queen’s Speech, has made road closures and outdoor leisure a permanent feature of some of central London’s neighboring High Streets.

Can’t empty commercial units also be rezoned, converted into affordable housing, bringing people to live in town centers, at the same time as doing away with uniform opening hours, so that central spaces might be alive at all hours, not just at pub hours at night. Some independents might close after lunch and reopen later in the early evening, stay open late, a feature, for instance, of the smallest, most provincial French towns, which tend to come alive at evening time, when in Britain their counterparts are deserted and already dead. Mightn’t we do away with uniformity altogether, put a ban on chains (get bold!), instigate commercial rent control, and induce people to experience a more obscure clue: namely that it (?) will happen here; yes, happen even on your High Street.

Why can’t central government empower local authorities to empower local, independent businesses? Real empowerment, I mean—empowerment of ideas. Many people, lacking money capital, have capital inside their heads awaiting realization. That’s the alternative. That’s the opportunity. Cities and small towns have lacked any sense of participatory democracy for a long while, and chains are a sure way to foster disempowerment in work and in urban life. Our retreat to online shopping is merely a symptom of High Street alienation. Yet it isn’t hi-tech urban design that’s at stake; more low-budget city acupuncture, of finding new ways to recreate old stuff, of poking into things meticulously and lovingly to enable sociability, like at the flea-market—not rolling in roughshod with the bulldozer and a new Tesco superstore.

It’s more about nurturing street space, developing floor-space, re-energizing vacant units. The essential thing is to construct a human space in which experiential communication can be most effectively transmitted. Streets are communicating vessels, after all, capillary tissuing, where exterior and interior worlds constantly interchange and flow into each other. Physicality morphs into sociality, and vice versa. The more we stay passive objects, in a wilderness of sameness, of mono-space, the less we actively participate in the production of our own life, and the less we get out of this life. Could there ever be a sense that curious objects might induce curious people to one day create curious cities?

Whether deliberate or subconscious, Empson said that the best poetry makes the best and subtlest uses of ambiguity. So should the best and subtlest urban planning and design. Maybe, then, we can conceive Empson’s critical and creative treatise about poetry as a manifesto about the form and functioning of our cities. At its best, the city is a sort of poetic text, with the same rhymes and rhythms, same ambivalences and ambiguities as those of the best literary refrains.

Whether deliberate or subconscious, Empson said that the best poetry makes the best and subtlest uses of ambiguity. So should the best and subtlest urban planning and design. Maybe, then, we can conceive Empson’s critical and creative treatise about poetry as a manifesto about the form and functioning of our cities. At its best, the city is a sort of poetic text, with the same rhymes and rhythms, same ambivalences and ambiguities as those of the best literary refrains.