I was in New York recently, where I once lived, some twenty-years back, there to visit my old friend and mentor, my old university teacher—and now he is old—an 88-year-old David Harvey, the world-renowned Marx scholar. I hadn’t seen him for a while and was keen to catch up, to hear his news and tell him some of my own, about my life in Rome, about my work on Gramsci. Ever so brilliant, it’s good to get some tips from David, some inspiration, a little encouragement, as well as a bit of critical feedback. As usual, too, in his company, we did a lot of talking and eating, some drinking, and together we rode the East River ferry over to Brooklyn and back, just for the fun of it, on a bitterly cold afternoon. It’s one of David’s favorite Big Apple past times; he does it alone most days; during Covid lockdowns, he said, it was an al fresco lifeline.

David is always working on some book or another and his latest is The Story of Capital, another iteration bringing Marx alive, of showing how the great bearded prophet can still help us understand our very troubled world. “The duty of the author,” says David in the book’s “mission” statement, “is to create an audience rather than to satisfy one. When Marx wrote,” he says, “most workers were illiterate. The audience he sought to shape was comprised largely of self-educated artisans in the throws of transformation into industrial labor. Marx sought to teach them that another world of laboring and living might be possible…In this book,” David says, “the perspective of the emancipated worker will be our helpmate and guide.”

During our conversations, we got onto the subject of Gramsci and his friend Piero Sraffa, whom David remembers from his undergraduate days at St. John’s College, Cambridge in the mid-1950s, whose grounds were next to Trinity’s, where Sraffa had a research fellowship. These days, David forgets plenty of things he did last week, but he vividly remembers seeing Sraffa well over half a century ago. He still holds the image of a middle-aged man standing, hands behind his back, staring at a twentysomething David and his pals playing tennis. Sraffa bizarrely held his gaze, appeared rather odd, like another eccentric Cambridge type. Afterward, wondering just who was this strange character staring at them, he was informed it was non-other than Piero Sraffa, the famous Italian economist, friend of an even more famous economist, John Maynard Keynes, and of an equally eccentric (and famous) philosopher called Ludwig Wittgenstein—and, of course, Sraffa was Antonio Gramsci’s final friend, an ever loyal friend, the only friend Gramsci had at the end of his life, one of the last people to see Gramsci alive. There he stood standing, looking at a young English Geography undergraduate who, decades later, living in New York, was destined to become a famous interpreter of Karl Marx.

David spoke about Sraffa’s economics, about his stellar reputation, about him never publishing much, about his magnum opus, The Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities, from 1960, a rather slim deal, barely reaching 100 pages, filled with as many simultaneous equations as actual written text. Sraffa was, by all accounts, a brilliant mathematician and logician, with a razor-sharp mind. Wittgenstein, himself no slouch at the intelligence stakes, said that after talking with Sraffa he felt like a tree that had just had its branches hacked off, pruned for its own good.

Yet, as a writer, Sraffa seemed forever blocked, finding it difficult to lay words down on the page, no matter what the language, whether in native Italian or adopted English. (He’s reputed to have begun The Production of Commodities in 1926!) He knew this, too, was painful aware of it, confessing to Gramsci’s sister-in-law Tatiana (August 23, 1931) that “in the past Nino [Gramsci] always chided me for having too many scientific scruples, saying that this stopped me from writing anything: I have never been cured of that illness.” Ironically, Sraffa sometimes threw this judgment back in Nino’s face, criticizing his work on the history of Italian intellectuals, joking that his friend was likewise crippled with those same “scruples,” wanting to read everything before he could say anything.

And Gramsci admitted as much to Tatiana (August 3, 1931), in a tone not unreminiscent of Piero’s: “you must remember that the habit of rigorous philological discipline acquired during my years at the university imbued me, perhaps excessively, with methodological scruples.” Tatiana didn’t contradict her brother-in-law: “you used to rebuke Piero constantly for his excessive scientific scruples that prevented him from writing anything; it seems that he has never cured himself of this illness, but is it possible that ten years of journalism have not cured you?”

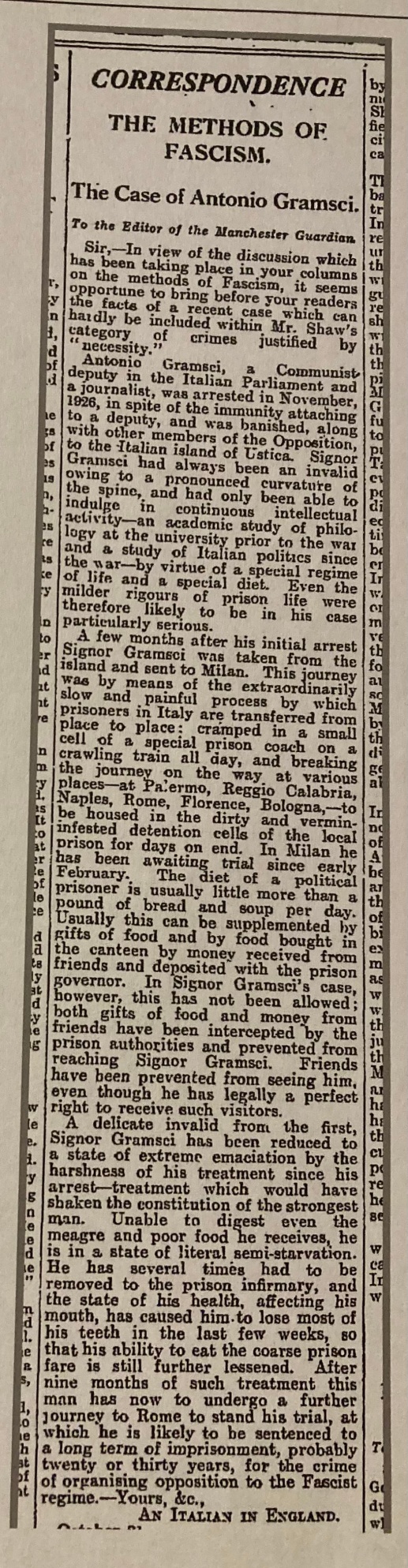

With Tatiana, Sraffa was the gossamer thread that connected Gramsci to the outside world. He co-managed Gramsci’s bureaucratic and administrative affairs; regularly visited his friend in confinement; picked up the tab of his friend’s medical bills (like the costs of Formica and Quisisana clinics); brought the criminality of Gramsci’s brush with fascism to international attention. Sraffa was instrumental in getting a letter, “The Methods of Fascism: The Case of Antonio Gramsci,” published in the Manchester Guardian (October 24, 1927), penned by “an Italian in England.”

Piero and Nino exchanged ideas, criticized one another, encouraged each other; Nino often used Piero, seven-years his junior, as an intellectual sounding board, as a trusted interlocutor, asking for advice, for suggestions, whether his friend could chase up a source, a book or journal, a magazine or newspaper article, could he confirm this fact and that, find out some precise detail about Croce’s historical studies, if Machiavelli ever wrote anything about economics, or David Ricardo about philosophy. Sraffa opened an account at a Milan bookstore, Sterling & Kupfer, from which Gramsci obtained unlimited numbers of books, as many as he was allowed on the inside.

Sraffa secured Gramsci a subscription to the Manchester Guardian, which Gramsci read with intent, practicing his English, preferring the northern broadsheet to the London Times: “London stands to Rome as Manchester to Milan,” he told Tatiana (January 26, 1931), “and the difference appears also in the weekly publications. Those of London are too full of weddings and births of lords and ladies and by comparison I still prefer pages about the cultivation of cotton in northern Egypt.” Gramsci asked Tania to write Sraffa, telling him: “I am making rapid progress in reading English; it is much easier for me than German. I read fairly rapidly.”

Sraffa, meantime, became an intermediary between Gramsci and the exiled PCI leadership, bivouacking in Paris; and he made trips to Moscow to see Gramsci’s wife and sons, relaying family news in both directions. Sraffa spent the summer of 1930 in the USSR visiting Giulia in a convalescence home. In August, he was joined by his Cambridge economics colleague Maurice Dobb, a party member, and together they did a series of guided factory tours.

Sraffa never renounced his political independence, was never a card carrier. He was “a communist without a party,” he said, a Marxist who hardly ever mentioned Marx, a radical who turned himself into a reserved English gent, as discreet in his public life as he was in his private life. The Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities is the epitome of such discretion, fascinating, as Sraffa’s other Cambridge colleague, Joan Robinson, said, “by the crystalline style in which it is written.” (David also remembers Joan Robinson at Cambridge, decked out in a Chinese jacket and red star Mao cap.) Without explicitly stating it, Sraffa justified Marx’s labor theory of value, that the rate of exploitation is more fundamental than the rate of profit on capital.

The Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities also quietly shredded neoclassical economic theory, pulling the rug from beneath the feet of bourgeois orthodoxy, demonstrating the tautology of its supply and demand nostrums. That the rate of profit is measured by the productivity of capital is a meaningless nonsense, Sraffa said, something that sent you round in vacuous circles: you have to know the level of prices to know the value of capital, and you have to know the rate of profit to know the level of prices. Supply and demand explains nothing, grips onto nothing, fetishizes everything. Sraffa sticks to his Marxian guns, agreeing with Marx (and Ricardo) that the prices of commodities are proportional to the labor-time required to produce them. The real nub of economic theory, he said, is value, the rate of exploitation of labor.

Sraffa was brilliant at revealing how prices relate to value. He offered an ingenious solution to the “transformation problem” in Marxist theory, using algebra to work out the conversion of commodity values into market prices, calculating how the rate of exploitation is related to the rate of profit on capital, a puzzle Sraffa reckoned was more analytical than actual. The real economics of capitalism, he said, functioned precisely as the Marx of Volume One of Capital had posited it. The equations, said Sraffa, qualifying his own contribution, “show that the conditions of exchange are entirely determined by the conditions of production.”

***

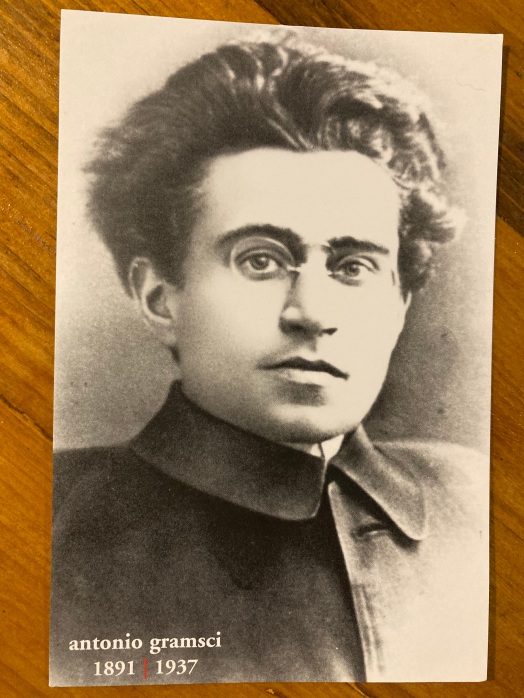

Gramsci and Sraffa first encountered each other in 1919, in Turin, via an intermediary, Umberto Cosmo, who’d actually taught Sraffa Italian at high school; Cosmo went on to hold a professorship at the University of Turin where Gramsci became one of his brightest literature students. When Gramsci founded the magazine L’Ordine Nuovo [The New Order] on May Day 1919, Sraffa joined its editorial team and soon their friendship thrived. Sraffa reported on economic affairs and penned several important articles on labor struggles in the US and Britain. (His name, though, never figured as author, nor was Sraffa ever listed on the magazine’s masthead.) L’Ordine Nuovo ran as a “weekly review of socialist culture”; “its only unifying sentiment,” Gramsci said, “arose out of a vague passion for a vague proletarian culture. We wanted to act, act, act.”

The paper sought to transcend sectarianism, promote open discussion, the exchange of ideas, and actively encouraged comradely disagreement and debate. No Party vehicle, never slavishly following any official line, its perspective, said Gramsci, was autonomous and international. In April 1924, he and Sraffa voiced their own pointed disagreement about how to fight fascism. “From an old subscriber and friend of L’Ordine Nuovo,” Gramsci cued Sraffa’s contribution, “we’ve received the following letter.” “I stand by my opinion,” Sraffa began, “that the working class is totally absent from political life. And I can only conclude that the Communist Party, today, can do nothing or almost nothing positive.”

Workers these days, Sraffa said, don’t see concrete problems as political problems: they present themselves as something resolvable “individually” and “privately,” as actions done purely “to preserve job, pay, house and family.” As such, said Sraffa, “I don’t think that a relaxation of fascist pressure can be secured by the Communist Party; today is the hour of democratic opposition, and I think it is necessary to let them proceed and even help them. What is necessary, first of all, is a bourgeois revolution, which will then allow the development of a working-class politics.”

The Communist Party “commits a grave error,” Sraffa said, “when it gives the impression it is sabotaging an alliance of oppositional forces”; it’s “only afterward, after the fall of fascism, that the Party will have to distinguish itself as the party of the masses; and certainly the Southern question and unity of the working classes and peasants will be in the forefront. But not today.” Its function for now, Sraffa concluded, signing off simply as “S.,” “is that of a coach-fly”—after La Fontaine’s fable, where a group of horses dragging a heavy load up a steep hill has a fly hovering over them; the fly believes it’s his own effort that makes the horses’ arduous ascent successful.

In his tart response, Gramsci said “this letter contains all the necessary and sufficient elements to liquidate a revolutionary organization such as our party is and must be. And yet, this isn’t the intention of our friend S., who even though he isn’t a member, even though he’s only on the fringes of our movement and propaganda, has faith in our party and considers it the only one capable of permanently resolving the problems posed and the situation created by fascism.” Our friend S., Gramsci said, treads on dangerous ground, reducing the efficacy of a powerful oppositional force. He dissolves its impact, relegates it to another reformist entity—to another passive non-force—which was part of the problem in letting fascism grow in the first place.

“Our friend S. doesn’t adopt the viewpoint of an organized party,” said Gramsci. “So he doesn’t perceive the consequences of his views or the numerous contradictions into which he falls.” What is required is a leading light, a beacon, Gramsci said, “a role of guide and vanguard,” and that’s precisely what the Communist Party offers—or should offer; “an organized fraction of the proletariat and of the peasant masses, i.e. of the classes which are today oppressed and crushed by fascism… If our party doesn’t find for today independent solutions of its own to Italian problems, the classes which are its natural base would turn over en masse toward other political currents.” Our friend S., in sum, “hasn’t yet succeeded in destroying in himself the ideological traces of his democratic-liberal intellectual formation, normative and Kantian rather than dialectical and Marxist.”

***

That strange figure David saw all those decades ago harbored something deep: he was one of the last people to see Gramsci alive twenty-years earlier. He and Gramsci met a final time at Quisisana clinic on March 25, 1937, in Rome, exactly a month and two days before Gramsci’s passing. With ever declining health, Gramsci had obtained yet another transfer, ridding himself of the Formia clinic, arriving at Quisisana on August 24, 1935, where, in northern Rome, he would conclude his days—not far from where this end had begun on November 8, 1926, on that long night of his arrest. When Sraffa came in March, Gramsci knew he was due to be released on April 21; he’d been considering his future, what he’d do as a free man, where he’d live. He and Sraffa discussed it.

Two options presented themselves to Gramsci: either emigrate to the USSR, rejoin his wife and sons, repair their relationship, and continue to pursue his political activities; or else return to Sardinia, retire, and try to recuperate his health in his native village. It seemed the former option was preferable to Gramsci, because Sraffa already had documentation from the Soviet authorities that would enable the process. At their meeting, Gramsci said he also had an important message he wanted his friend to convey to the PCI leadership in Paris, a piece of advice, a recommendation about its strategy, about what it should do after the fall of fascism, which, like Gramsci, appeared on its death throes.

Gramsci’s position had now taken on a new turn, evolving since his disagreement with Sraffa a decade or so prior. No longer did he believe there could be a direct passage from fascism to socialism. Some interim position, a tactical transitional phase would be necessary, and here the only realistic option, he said, was to develop a “Constituent Assembly,” an alliance between the PCI and other anti-fascist parties. Thus his message to the PCI: “The Popular Front in Italy is the Constituent Assembly.” Pass it on.

The record indicates that, as ever, Sraffa was loyal to his friend. He immediately communicated Gramsci’s message to Togliatti, through the intermediary Mario Montagnana, Togliatti’s brother-in-law, a member of the PCI Central Committee in Paris. Years later, in a letter dated December 18, 1969, addressed to the labor historian Paolo Spriano, Sraffa declared: “I remember with certainty one of the last times I visited him at the Quisisana in Rome, Gramsci asked me to transmit his urgent recommendation that the policy position of the Constituent Assembly be adopted; I reported this in Paris.”

What did Party bigwigs make of Gramsci’s recommendation? It’s hard to tell. Negatively, likely, incredulously, probably; maybe Gramsci was proposing something that further isolated him from Togliatti et al., from those men at the top? Was it a volte-face by the Party’s co-founder? Had the fascists softened him, eventually destroyed his brain, finally stopped it from working? Or had his terrible ordeal and sufferings made him acutely aware of the gravity of the situation—one in which the Party’s cushy leadership, safe and sound in a distant city, had little real inkling? Maybe Gramsci’s affirmation of a Constituent Assembly mimicked the pragmatism of Soviet’s New Economic Policy (NEP), when, in 1922, Lenin insisted on a little dose of free market capitalism to help stimulate the ailing communist economy, allowing state enterprises to operate on a profit basis.

Or maybe it was simply Gramsci’s savvy realpolitik, a leaf out of the playbook of his hero, Machiavelli. Now, the most efficacious immediate strategy of Gramsci’s party, of the Modern Prince—which, remember, is no longer a superior individual leader but the popular masses wedded to the party—is that of the wily fox not the roaring lion. Thirteen-years on, Gramsci knew all-too-well the traps and snares out to ambush the lion, understood them because he’d fallen for them. Now, he recognized that the struggle for post-fascist hegemony required a period of consent, of incorporation and inclusiveness—not of direct oppositional assault. Had Sraffa been right all along?

On the other hand, maybe this just harked back to the so-called “dual perspective,” something Gramsci had outlined in notebook 13 on Machiavelli, discussing it with his fellow inmates at Turi prison as early as 1930. It was really all about the ebb and flow of political action, the vicissitudes and vagaries of doing politics, where force and consent, fortune and virtue change, blow in the wind, and any Modern Prince needed to anticipate in which direction it breezed. After fascism’s demise, and prior to the proletariat seizing power, Gramsci thought there’d likely be an intervening, transitional period; the Party should take this into account. He didn’t see any absolute separation between the moment of consent and the moment of force, between reform and revolution: it wasn’t about two forms of “immediacy,” Gramsci said, “which succeed each other mechanically in time.” Rather, the two co-exist and represent two ways of fighting, provided they’re dialectically conjoined.

The important thing, Gramsci said, “is seeing them clearly: in other words, accurately identifying the fundamental and permanent elements of the process.” He again illustrates the point through Machiavelli, his favored man of thought and action, a partisan and creator, “an initiator” who spoke to Gramsci “in the future tense” (as Althusser said), Italy’s first Jacobin. “Machiavelli neither creates from nothing,” Gramsci said, “nor does he move in the turbid void of his own desires and dreams. He bases himself on effective reality” (emphasis added). And so, perhaps, now, in 1937, near the end of his life, offering it as a sort of last political will and testament, Gramsci recognized that the most effective reality was the “Constitutional Assembly,” something politically “conjunctual” rather than “organic.” The Modern Prince, Gramsci knew, just as the old Prince of Machiavelli knew, that in politics you’re judged by only one criterion: success.

***

Interestingly, a fellow inmate of Gramsci’s at Turi prison, another political prisoner, was a former railway worker and Party member called Athos Lisa. Lisa (born 1890) was almost an exact contemporary of Gramsci’s and remembers the two-week stint of morning lectures Gramsci gave prisoners in the autumn of 1930. Lisa’s “Report” on Gramsci’s political views in prison formed part of a memoir, kept secret in Lisa’s lifetime, and only discovered by his widow after Lisa’s death in 1965, tucked away in the bottom of his desk drawer. (An English translation of this “Report” appears as an “Annexe” to Perry Anderson’s book version of The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci.)

Lisa’s “Report” claimed Togliatti concealed Gramsci’s message about the Constituent Assembly, passed on by Sraffa, because the PCI was peddling its own illusions that a socialist revolution was just around the corner, and that the Party was the only opposition to fascism. Togliatti, in other words, rejected Gramsci’s views. But Lisa made it clear that, for Gramsci, the Constituent Assembly wasn’t a permanent state of PCI Being, only a temporary waystation toward a more distant goal, and this goal remained steadfastly communist, an affirmation rather than dilution of Gramsci’s militant politics.

He was still fully committed to overthrowing the capitalist state, through military organization and violence, if necessary, through revolution. The Party needed to create hegemony in the classic Leninist sense, laying the groundwork for its “war of position,” developing the conditions for the decisive moment of struggle when heavy hammer blows could be inflicted on the bourgeois state apparatus, shattering it irrevocably; and a new form of government would succeed it, a socialist state—an “integral state,” Machiavelli had called it.

Under Togliatti’s watch, the PCI buried Gramsci’s view not because of its reformism but because of its revolutionary thrust, going much further to the Left than anything the Party was really envisaging, notwithstanding its anti-capitalist bluster. For that reason, said Lisa, Gramsci announced his lecture series as “a punch in the eye” to the PCI’s official line. What’s more, after the fall of fascism, Gramsci said that Italy must purge itself of its reactionary past, that every fascist minister should be banished from the state apparatus, for good, excluded from ever practicing government anywhere, in any capacity, at all times.

As history had it, in 1946 a Constituent Assembly became political reality in Italy, took over the helm of government, yet with a bitter twist—with a punch in the eye, if you will, to Gramsci. To be sure, almost every politician and prefect who’d served under Mussolini remained in office somewhere, and their careers prospered, including Enrico Macis, the infamous Judge of the Special Tribunal who’d sentenced Gramsci to his slow prison death. (Between 1927 and 1943, this Special Tribunal had passed over 4,500 sentences, totalling around 28,000 years of imprisonment, including 42 death sentences, of which 31 were fulfilled.) And, incidentally, in that same 1946 government, was Gramsci’s former PCI running mate, Palmiro Togliatti, who became Minister of Justice. The PCI’s rightward drift was assured, had commenced early, silently and unabatedly, and would continue its slide until eventual dissolution on February 3, 1991.

***

“Dear Friend,” wrote Tatiana to Sraffa on May 12, 1937, “I waited so long to answer and to describe our great misfortune in detail… I want you to write to me whether you think it useful, or, rather, absolutely necessary, that you put Nino’s manuscripts in order.” “I thought it best to put off sending anything,” Tatiana said, “in order to find out whether you are willing to take charge of, and revise, this material, with the help of one of us in the family.”

“The cremation has already taken place,” Tatiana told Sraffa, almost matter-of-factly. “Nino suffered a cerebral hemorrhage the evening of April twenty-fifth.” That day, she said, he seemed his usual self, maybe even more serene than he had been of late. He ate his dinner as usual, soup with pasta, a fruit compote, and a bit of sponge cake. Then he left to go to the bathroom. But he was brought back in a chair, carried by several clinic nursing staff. He’d had a seizure, lost control of the whole of his left side, and collapsed on the floor, managing to crawl to the bathroom door to cry out for help. He was put back into bed and attended to by assorted doctors.

Nino lost all sensitivity and mobility on his left side, Tatiana said, and became very weary. The doctors applied leeches to bleed him yet he started vomiting and breathing with difficulty. The patient’s condition, doctors said, was “extremely grave.” “I was forced to protest violently against the priest and sisters who came in,” Tatiana told Sraffa, “so that they left Antonio alone.” Then he seemed to settle and breath more easily. “But twenty-four hours after the attack,” Tatiana said, “the violent vomiting began again, and his breathing became terribly painful.” “I kept watch over him all the time. But he took a last deep breath and sunk into a silence that never could change.” The doctor confirmed Tatiana’s deepest fears, that he was gone, that it was all over, at 4.10am on April twenty-seventh; the sisters came to carry his diminutive body to the mortuary chamber.

Rome’s Police Chief issued the following notice that same day: “I report that the transportation of the body known as Antonio Gramsci, accompanied only by relatives, took place this evening at 19:30. The hearse proceeded at a trot from the clinic to the Verano cemetery where the body was deposited to await cremation.”

“Carlo and I were the only persons present,” Tatiana said in her letter to Sraffa, “except for the numerous police guards who followed the body out and watched the cremation. Now the ashes have been deposited in a zinc box, laid inside a wooden one and set in a place reserved by the government…I will request authorization to transport it.”

***

Tatiana miraculously smuggled Gramsci’s manuscripts out of the Quisisana clinic, Lord knows how, and Sraffa’s friend, Raffaele Mattioli, Managing Director of the Banca Commerciale Italia, helped her use a safe deposit box at the bank’s Rome head office, to preserve the notebooks, keeping them out of the dirty maulers of the fascist authorities. Later, they were mailed to the USSR, arriving in Moscow in July 1938, a little more than a year after Gramsci’s death. At the Quisisana clinic, a memorial plaque was put up in the deceased communist’s honor, yet has since been removed: the clinic’s owner, Giuseppe Ciarrapico, who died in 2019, aged 85, had requested it in his will. In recent times, the plot has thickened and now Left and Right tussle around the legacy of Gramsci at Quisisana.

Ciarrapico himself was a former senator in Silvio Berlusconi’s Popolo delle Libertà [The People of Freedom] party, a redoubtable fascist and multimillionaire embezzler, convicted several times for financial misdemeanors, helping himself in the early 2000s to 20 million euros of public monies. Along with an array of health clinics (like the Quisisana), Ciarrapico owned bottled water plants, restaurants, air-taxi services, publishing houses and newspapers, and was President and owner of A.S. Roma football club, which he’d acquired in 1991. A nasty character, of a nasty family, who still own Quisisana.

In December 2023, the cold case of getting a plaque installed at Gramsci’s death site reopened. After a presentation of the agenda at Rome city council, incumbent Democratic Party (PD) Mayor Roberto Gualtieri said he was committed to the proposed plaque, born out a petition organized by the leftist newspaper Il Manifesto, with over 2,500 signatories. The Quisisana clinic confirmed it was “largely satisfied” with the favorable vote for affixing a commemoration, likely something erected on the inside rather than on the outside. “The vote,” commented the first signatory, Erica Battaglia (PD), “allows for a faster and more inclusive process to give just memory to one of the most important political and philosophical thinkers of the twentieth century.”

After I returned from New York, I was curious if there’d been any activity at Quisisana, any hint that a plaque might go up somewhere soon? And so off I went again on another little Gramsci adventure, visiting another site of his buried past, riding a Lime rental bike the four miles or so from my Monti home, journeying beyond Villa Borghese, to the clinic that today is known as Casa di Cura di Quisisana, in the smart bourgie neighborhood of Parioli.

Along via Gran Giacomo Porro, Casa di Cura di Quisisana is plush with its marble pillared rotunda entrance. Flanked by luscious palm trees, it looks more like the glitzy casino at Monte Carlo than any healthcare institution; the mind boggles comparing it with what the British National Health Service (NHS) could ever serve up. The security guard at the reception paid me no attention as I waltzed in, faking authority, looking like I knew where I was, where I was headed, and I ventured toward the clinic’s pleasant little café to the left, with bright sunshine flooding through its windowed back wall. I ordered an obligatory espresso, which I drank, as you do, in a couple of gulps standing at the bar. Then I sat down, surveyed the surroundings, looking at the crucifixes adorning the walls, at the well-heeled people coming and going. I’ve no idea whether the clinic was as upscale in Gramsci’s day, whose costs were borne by Sraffa. What I do know is that Gramsci was under constant police surveillance here, and never left the premises.

On one wall I noticed a framed photograph showing Quisisana under construction, with its scaffolding gaping, and I couldn’t help noticing the date—1926—ironically the year of Gramsci’s arrest. As I sat there, I held my own private communion: I was tremendously moved by the thought that, here, 87 years ago, Gramsci died, in this very building, and I was sitting in it, in Rome, now, it was incredible, on a Friday afternoon in April, a beautiful warm sunny day, thinking wouldn’t it be nice to see a large mural of Gramsci in the café on one of its walls; maybe an image of him in his youth, looking vibrant and a little dash, with a simple inscription below—I don’t know, maybe something like, è qui che morti Gramsci. It was here where Gramsci died. Wishful thinking, perhaps, because we’ll have to wait and see what transpires, what Rome city council’s motion might eventually bring forth, and what the rightist Ciarrapico family accepts in its private fiefdom. Watch this space…

Dear Andy,

Well, another fine essay. Great transition from Professor Harvey to Sraffa. I read Sraffa’s book a long time ago, read it a couple times. It’s a difficult book, but I got the gist of it. I think he began work on it around 1926. I used to laugh thinking how Sraffa would have been denied tenure in a US university for taking so long to write a short book! In 1925, Sraffa published an essay in Italian titled (in English) “On the Relationship between Costs and Quantity Produced” that demolished the neoclassical theory of supply and demand as developed by economists like Alfred Marshall (Keynes’s father was a contemporary of Marshall). In doing so, he referred back to Ricardo and the law of diminishing returns. Sraffa served as editor, with Dobb, of Ricardo’s works and correspondence.

When I began teaching, I was in the midst of trying to understand the famous Cambridge Controversies in the Theory of Capital, which is when I probably read Sraffa. I wrote a long paper for a graduate seminar in Labor Economics about the controversy, focusing on the determinants of the split between labor and capital in the distribution of income. My paper was filled with math and graphs, not high-class math but a lot more than what I now know. I was commuting between Johnstown and Pittsburgh to finish my PhD coursework, a long drive and a lot of work, given that I was teaching five classes a term, with multiple preparations. My professor, Arnold Katz, was a diehard neoclassical economist and he said he didn’t understand my paper. But he was principled, almost to a fault, and he gave the paper to David Houston, my favorite prof and a radical familiar with what I wrote. David gave me an A and suggested I get it published. But I was too insecure then to imagine it was worth publishing.

It was great to read about Sraffa and Gramsci. I knew a little about them,but you filled in the gaps in a very fine way. Touching as well. I was talking to Martin on the phone yesterday and I told him about your Gramsci essays. He was very enthusiastic about a book! As am I. So, if you put it together, I am sure we will publish it. It is a great story, well-worth telling. And your style is exceptional. Readers will love it I am certain.

Just another little story: Joan Robinson was of course critical in the Controversy. The first essay I sent to MR, in 1972, was a critique of something she had published in MR. Paul Sweezy sent me the nicest rejection letter, saying that my piece was a bit too complicated for MR readers. But probably closer to the truth was that MR was not about to publish a critique of Robinson, who had moved steadily to the left. Sraffa had a big influence on her and no doubt Sweezy, because neither could see how markets could be perfectly competitive. The tendency was toward oligopoly, a la Marx’s insight that the concentration of capital was the norm. Even Adam Smith knew this. And yet, today, neoclassical nonsense reigns supreme. I doubt one econ grad student in 1,000 has ever heard of Sraffa or Robinson or Sweezy. Maybe even Keynes. At least in the US. And for sure, Gramsci would be a complete unknown. But the more you write about him, the more important he seems to be. Every radical would do well to meet him through his works. And soon, through your book.

Take care,

Michael

LikeLike

Pingback: Andy Merrifield, “Gramsci and his friend ‘S’” | Progressive Geographies