It’s easy to miss the Fondazione Gramsci, tucked away off the street in a little building along via Sebino, at number 43A, in Rome’s Trieste neighborhood. Its glass door entrance lies at the end of a discreet courtyard, modestly beyond the gaze of any undiscerning passersby. On the afternoon of my visit–a mild, gray, late January day–things were brightened by the warm welcome I’d received. I said I was a big Gramsci fan, had written a few things about him, and came curious about the Fondazione’s resources. I’d heard about their extensive library, crammed with every Left book under the sun, in scores of languages, which I now saw filling the glass cabinets on the walls of the main biblioteca. I said I wanted to tap Gramsci’s digital archive as well, especially those legendary prison notebooks, whose real thing, I knew, were housed in a special vault somewhere on the Fondazione’s premises.

Those premises reminded me a lot of the long-lost Brecht Forum in New York—the same low-tech shabbiness, a bit worn and grungy. The array of tatty desktops harked back to another age, somehow bygone, pre-Apple. The Fondazione’s young librarian came over to assist me, going out of her way to log me onto the system’s mainframe, telling me in perfect English that she had digitized much of the Gramsci material, all to be scrutinized without cost or subscription, with a clarity that almost lets you smudge your own fingers in Gramsci’s ink. Working so intimately with Gramsci’s writings must have been very exciting, I say to her. She smiled. “Yes,” she said, “it was.” She loves her job.

Now, we can inspect for ourselves Gramsci’s meticulous notebooks, his perfectly legible cursive, his precise crossings-out, done with exactitude, with a ruler, diagonal lines methodically scoring out words, sometimes whole pages; Gramsci added and eliminated text with characteristic calculation. His handwriting is so neat, so error free, that we know it represents ideas and material already worked through, already drafted out in rough beforehand. Here we have “special,” self-copyedited, clean versions of his thought, preserved for immortality.

Gramsci was finicky about the type of notebook he wanted. He wrote his sister-in-law Tania (February 22, 1932), “can you send me some notebooks, but not like the ones you sent me a while ago, which are too cumbersome and too large; you should choose notebooks of a normal format like those used in school, and not too many pages, at the most forty or fifty, so that they are not inevitably transformed into increasingly jumbled miscellaneous tomes. I would like to have smaller notebooks for the purpose of collating these notes, dividing them by subject, and so once and for all putting them in order. This will help me pass the time and will be useful to me personally in achieving a certain intellectual order.”

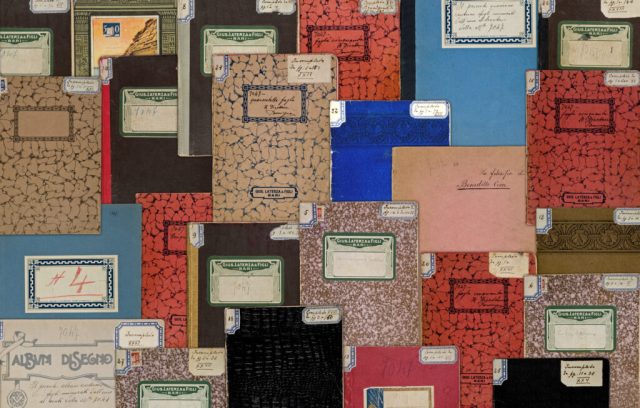

Each notebook bears on its cover the imprint “Gius. Laterza & Figli”–Giuseppe Laterza & Sons, a Bari-based family business, a stationer and publisher (still around to this day). Some covers are ornately designed, with elaborate art deco patterning; a few have images of ancient Egypt; all have front labelling marked with Gramsci’s prison number, 7047, together with a sentence he wrote, indicating the subject matter inside. After Gramsci’s death, Tania glued another marker on the upper righthand side, deeming each notebook either “Completo” or “Incompleto,” while assigning them Roman numerals. The bulk of the notebooks are 15 X 20.6 cm in size, containing 97 leaves with twenty-one, single-spaced lines on each sheet. The parsimonious Gramsci wasted nothing, filling up both sides of the page.

A few notebooks are larger format, 20.8 X 26.7 cm, and in one, atypical case, Quaderno XXXI from 1932, he used an artist’s sketchpad, 23 X 15 cm, blank-paged, with a beautiful deco Album Disegno frontispiece, marked “Incompleto” by Tania. Gramsci had singled-out here his translation of the Brothers Grimms’ tale about a little goblin called “Rumpelstilzchen” (retaining its original German spelling), copying it out in neat, corrected form for his sister Teresina’s children in Ghilarza. The write-up was never completed, even though Gramsci had finished the translation two-years earlier, appearing in full alongside other Brothers Grimm stories in Quaderno B (XV).

Gramsci told Teresina (January 18, 1932) “I’ve translated from German, as an exercise, a series of popular tales, exactly like the ones we liked so much when we were children and that actually resemble them to some extent, because their origin is the same. They’re a bit old-fashioned, homespun, but modern life, with the radio, airplane, the talkies…has still not penetrated Ghilarza deeply enough for the taste of today’s children to be very different from ours at that time. I’ll make sure to copy them in a notebook and send them to you as soon as I get permission, as a contribution to the imagination of the little ones. Perhaps the person who reads them will have to add a pinch of irony and indulgence in presenting them to the listeners, as a concession to modernity.”

Gramsci gives pride of place to Rumpelstiltskin, labeling the eponymous protagonist “coboldo” and not the “tremotino” used in more standard Italian translations. “Coboldo,” from the Latin cobalus (meaning “rogue”), comes close to the English “kobold,” from pagan mythology, a hobgoblin who haunts households and plays mischievous tricks, especially if it feels neglected or offended; Gramsci says the tale reminded him of the Sardinian folkloric legends that had kindled his own homespun island imagination. If anything, Gramsci physically resembled the deformed goblin–tiny and hunchbacked; both, too, were outsiders and pariahs with mischievous, stubborn streaks. Remember Gramsci refused to plead for clemency, seeing that as a capitulation to fascism, as an implicit admission that he’d recanted his Marxist views. In this sense, the frank, if austere, goblin way spoke personally to the sly and stoic Gramsci, appealed to him as a state of being in the capitalist world.

Rumpelstiltskin said his name was unusual and Gramsci sometimes said his own name was unusual, too. Is your name “Gasparo, Mechiore, Baldassare?” the queen asked the goblin in Gramsci’s translation. “Is it Gatarino, Saltamontore, Tombatore? Giovanni or Giuseppe?” In “my journey through this ‘great and terrible world’,” Gramsci tells Tania (February 19, 1927), “I’m not known outside a rather restricted circle; therefore my name is mangled in the most unlikely ways: Gramasci, Granusci, Gramisci, even Garamascon, with all the most bizarre in-betweens.”

The goblin, like Gramsci, is portrayed as the villain, when the real villains–the miller, his daughter, the king–are presented as good and upright; it’s they who live happily ever after. And yet, Rumpelstiltskin is the only honest soul amongst them, the only character true to his word. The miller is a liar who gives away his daughter to the king. The miller says she can spin straw into gold, which she can’t. The king, who’s nasty and greedy, is impressed. He carts her off and locks her up in a dungeon with a spinning wheel. If she can turn the piles of straw into gold then he’ll marry her; if not, it’s off with her head. The king is excited at the prospect of so much wealth and will stop at nothing to get it. “I’ll be back in the morning for the gold,” he says. As night falls, the girl is at a loss living up to her father’s conceited promise. She starts to cry.

Suddenly, a funny little goblin appears, asking the reason for her tears. He listens with a sympathetic ear. After she explains, he laughs. “Is that all? Why, I can do that in a twinkle,” he says nonchalantly. For him, you don’t have to be very clever to spin lots of gold (they do it all the time on the stock market, spinning yarns all the way to the bank); nor do you have to work particularly hard. Rumpelstiltskin knows that making lots of money is no big deal, that there are other paradigms to life, other less venal and more magical ways to find fulfilment. He spins the gold in return for the girl’s pretty necklace.

Next morning, the king is delighted. That evening, Rumpelstiltskin returns and spins more gold, this time in exchange for the girl’s ring. The king, again, is thrilled. On the third evening, the miller’s daughter has nothing more to give the goblin, so she promises him her first-born child. This time, he fills the whole room with gold, and the king goes wild with excitement and marries the girl that very same day. The kingdom rejoices at the marriage and later at the birth of the queen’s beautiful daughter.

When the goblin hears the news, he comes back for the baby. “Remember,” he says, “there was an agreement, and you’re bound by that.” The queen weeps, goes down on her knees, begs him not to take her baby away. Again, the goblin sympathizes, and says, “All right, my name is unusual, if you can guess it, you’re released from the promise.” He’ll be back tomorrow, he says. But the queen plays crooked and sends a servant to snoop and find out his name. A while later, the servant returns, grinning all over. “I followed him to a little shack, deep in the forest, and there I heard him singing his song, and he bawled out his name.” Next morning, the goblin reappears before the queen. She utters his name and, “spitting and squealing, he vanished out of the window like a balloon when you take your fingers off the nozzle.” Nothing is ever heard of him again. Meanwhile, the king, the queen, and the young princess live happily…blah, blah, blah.

This warped and shallow value system is inculcated in us early. If you follow its rules, you get rewarded accordingly. You’ll live happily ever after, not rot in jail. But the reality of the tale is that its winners do everything we know a ruling class does: it lies and cheats, boasts and breaks deals, spies on you if need be, and always sends others to do its dirty work. Moreover, it rarely keeps its word. The queen breaks her compact. The king has no other interest than accumulating wealth; he doesn’t even love the woman he married. Everybody is duplicitous and conniving. They’re all phony schemers, out to extract something from somebody else–all except the ugly goblin Rumpelstiltskin.

In all, Gramsci translated twenty-four Brothers Grimm tales (actually twenty-three with one unfinished piece). They’ve since been collected together under the rubric Favole di libertà: la fiabe dei Fratelli Grimm tradotte in carcere, implying that if your body is incarcerated, then there are other possibilities to reimagine a liberty of the mind, a liberty of the imagination; and Gramsci seems drawn to fairytales for these motives. He knew the Brothers Grimm’s work was firmly rooted in German folklore, just as his own Marxism was rooted in Italian folklore, in its culture and regionalism, in its “non-official” subaltern tradition.

Some of Gramsci’s translations are done for personal amusement; others to gift to nephews and nieces who never knew Uncle Antonio. Despite the simplicity and naivety of the tales, Gramsci thought there was something here for adults, too, something political about folkloric tales, about their function within a particular oppressed stratum of society; an educative element, which is why, in Quaderno 27 (XI), he devotes singular attention to “observations on folklore” [Osservazioni sul folclore]. Gramsci suggests folklore should be studied as “a conception of the world and life implicit to a large strata of society, in opposition to ‘official’ conceptions of the world.” It has, he says, “sturdy historical roots” and “is tenaciously entwined in the psychology of specific popular strata.”

Gramsci, as ever, is dialectical, conceiving folklore critically and inquisitively, not narrow-mindedly. “Folklore mustn’t be considered an eccentricity,” he insists, “as an oddity or a picturesque element, but as something which is very serious and is to be taken seriously.” And he takes it seriously, even while he sometimes laughs out loud. He acknowledges its ties with religion and superstition, to “crude and mutilated thought.” Nonetheless, with folklore, “one must distinguish various strata,” Gramsci says, “the fossilized ones which reflect conditions of past life and are therefore conservative and reactionary, and those which consist of a series of innovations, often creative and progressive, determined spontaneously by forms of life which are in the process of developing, in contradiction to the morality of the governing strata.” “Only in this way,” says Gramsci, “will the teaching of folklore be more efficient and really bring about the birth of a new culture among the broad popular masses.”

***

As I was leaving the Fondazione Gramsci, the young librarian urged me to help myself to Gramsci paraphernalia on a bookshelf near the door, to books and pamphlets, as well as to wonderful Fondazione-produced postcards of the covers of Quaderni del carcere, in gleaming color. It was a treasure trove of Gramscian regalia. I wasted no time packing my shoulder bag with a big-formatted Fondazione publication called Antonio Gramsci e la grande Guerra, lavishly illustrated with fascinating reproductions of pre-prison Gramsci letters (from 1915-16), on Avanti! (Edizione Torinese) headed notepaper. I also bagged an interesting French booklet entitled Les cahiers de prison et la France, together with a text, Gramsci in Gran Bretagna, discussing the reception of Gramsci in the UK, notably the brilliant reinterpretations of Eric Hobsbawm, Perry Anderson, and Stuart Hall. And, needless to say, I grabbed a stash of those glossy postcards.

Exiting, and reflecting upon what I’d just seen in the archive, I realized how much of what Gramsci wrote was really about self-expression, about collecting and collating his own thoughts, putting them in intellectual order, clarifying his own position often vis-à-vis an antagonist. Before his arrest, Gramsci saw himself as a journalist-activist. He never wrote elaborate tomes, extended monographs, never had any inclination to do so. His writings were short, pithy, quickly drafted political interventions, polemical engagements with the urgency of the moment.

“In ten years of journalism,” he told Tania (September 7, 1931), “I wrote enough lines to fill fifteen or twenty volumes of 400 pages each, but they were written for the day and, in my opinion, were supposed to die with the day. I have always refused to permit publication of a collection of them, even a limited one.” In 1918, an Italian publisher wanted to publish his Avanti! articles, with “a friendly and laudatory preface,” “but I refused to allow it,” Gramsci says. A couple of years on, he apparently had a change of heart, letting Giuseppe Prezzolini’s publishing house convince him to issue a collection of newspaper pieces. But then suddenly got cold feet and told Tania, “I chose to pay the cost of the part of the type already set and withdrew the manuscript.”

Still, a major component of those writings, both inside and outside prison, had an explicit pedagogic intent: that of popularizing Marxism, of trying to communicate socialist ideas with an immediacy that resonated with a wider, lay public, sometimes with an immediacy that resonated with Gramsci himself. Large tracks of the prison notebooks were really thoughts toward Gramsci’s own version of a “Popular Manual of Marxism,” doubtless in mind when musing on folklore and common sense, and certainly in mind when launching his “critical notes” against Bukharin’s “Popular Manual.” The “Popular Manual” was Gramsci’s shorthand for Nikolai Bukharin’s Theory of Historical Materialism: A Popular Manual of Marxist Sociology, published in Moscow in 1921. What disappointed Gramsci most of all here was its missed opportunity: the book’s promising subtitle bore scant resemblance to its contents.

Bukharin’s position expressed the vulgar materialism of the era, Gramsci says, reducing Marxism to a positivist (and positive) science. (In the 1930s, Bukharin himself became a skeptic of Stalin’s regime, opposed the first Five-Year Plan and the collectivization of agriculture. Accused of conspiracy, a show trial found him guilty. He was executed in 1938.) Bukharin, says Gramsci, began all wrongly, and “should have taken as his starting point a critical analysis of the philosophy of common sense.” Common sense, says Gramsci, “is the folklore of philosophy, and, like folklore, takes countless different forms.” Common sense needs transcending, for sure, not wholesale rejection. It’s the breeding ground of good sense, after all, of a materialism much more realistic and a lot richer than Bukharin’s, something both critical and curious, open and ironic, maybe even folkloric—a mischievous “goblin” sort of Marxism that speaks the twisted language of ordinary people, for better or for worse.

One thing surely not lost on Gramsci when translating the Brothers Grimm is how God awful their characters are, how scheming and duplicitous, how untruthful and dishonest. Some Grimm tales are just that: grim, darn right nasty, and their moral message is hard to grasp—if, indeed, there is any moral message to grasp. It’s like reading the daily news. You know, once upon a time there was a nasty ex-President who wanted to seize power again… Maybe that’s Gramsci’s point? That life actually is “great and terrible,” and only by confronting its pitfalls and perils, its terrors and turmoil head on, never capitulating before its nastiness, can we hope to maximize a great that’s increasingly hard to see.

Pessimism or optimism? Gramsci probably wouldn’t have framed it as such, never would have conceived our world nowadays so dualistically, so either/or. This is him talking in 1929, powerfully articulating his position to younger brother Carlo: “humans bear within themselves the source of their own moral strength, that everything depends on us, on our energy, on our will, on the iron coherence of the aims that we set ourselves and the means we adopt to realize them, that we will never again despair and lapse into those vulgar, banal states of mind that are pessimism and optimism. My state of mind syntheses these two emotions and overcomes them.” Gramsci’s fairytales, we might say, spin yarns about the realm of necessity.

Dear Andy,

This is another wonderful essay on Gramsci. The museum must have made for a great visit. You are fortunate to live in Rome. Are you happy with your decision to move there? I love the way you humanize Gramsci. The story of his notebooks helps show the kind of person he was. He must have been so sad that he couldn’t see his family. His friend Sraffa, far away in England, must have felt alone and sad too, for his friend.

My friend Elly Leary reviewed my book, In and Out of the Working Class, for Monthly Review. She titled the review, Gramsci’s Grandchild. I was truly honored by this, although the great Sardinian shone as one of the brightest stars in the firmament, while I am a simple cog in the wheel of the struggle for the world Gramsci fought for so brilliantly.

His understanding of folklore and common sense was insightful. As are your essays, from which I am learning so much.

Take care and as an Italian friend just wrote to me, alla prossima!

Michael

LikeLike

Pingback: Andy Merrifield, Gramsci’s Goblin – on the notebooks and his translations of the Brothers Grimm fairytales | Progressive Geographies

Dear Andy,

have the Favole been translated into English? Would that even be possible? (I’m imagining an annotated edition that explains the translation choices in the way you did here…)

LikeLike

There are plenty of Brothers Grimm translations in English, of course, but to my knowledge none of Gramsci’s own. It would be nice to have them as you say: annotated, explaining the translation choices. Maybe one day! Thanks for question.

LikeLike

hehe, yes, I meant Gramsci’s… thanks…

LikeLike